Reading Group Guide

Discussion Questions

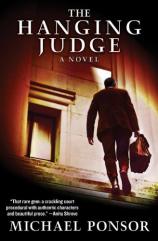

The Hanging Judge

THE HANGING JUDGE is sure to provoke many questions for your reading group. The author, Michael Ponsor, is an expert on the subject of criminal law --- but there are many ways that we, as readers, bring our own knowledge and opinions into our reading of the book.

Capital Punishment in Literature and Film

Films like The Green Mile, Dead Man Walking and The Life of David Gale have all contributed dramatic representations of capital punishment to popular culture. And in literature, THE HANGING JUDGE stands on the shoulders of some very famous giants, like John Grisham’s THE CONFESSION, Truman Capote’s IN COLD BLOOD, and Scott Turow’s legal suspense novels, as well as ULTIMATE PUNISHMENT, his memoir on being a lawyer involved in the death penalty. And most recently, Elizabeth Silver’s novel THE EXECUTION OF NOA P. SINGLETON posed difficult questions in the voice of an accused murderer.

A History of Capital Punishment

Massachusetts, where THE HANGING JUDGE takes place, has a long history with the death penalty: Its first hanging execution was in 1630. Right now, there is no state death penalty, though the federal government prosecutes capital cases within Massachusetts. Since 1630, there have been approximately 345 executions in the state, including 26 executions of people convicted of practicing witchcraft during the Salem witch trials. On November 7, 2007, House lawmakers rejected a bill to reinstate the death penalty by a vote of 46 to 110.

In the rest of the U.S., the death penalty is currently a legal sentence in 35 states as well as the federal civilian and military legal systems. Since capital punishment was reinstated in 1976, Texas has performed the most executions, and through mid-2011, Oklahoma has had the highest per capita execution rate.

THE HANGING JUDGE is dedicated to Dominic Daley and James Halligan. Who were these two? They were Irish immigrants who were ultimately put to death in a robbery case in 1806, due to what is now acknowledged to have been anti-Catholic bias. Daley and Halligan were held for five months, and only granted legal defense 48 hours before their trial. They were convicted within minutes-and it is this case that Ponsor weaves into the narrative of his fictional contemporary capital punishment trial.

As with many novels and films that depict jury trials, the reader of THE HANGING JUDGE is privy to more information about the defendant and the crime he is accused of than the story’s trial jurors are. How many members of your reading group agree with the jury’s verdict in THE HANGING JUDGE? Would any of you answer differently if you had not witnessed the sidebar conversations between Judge Norcross, Defense Attorney Bill Redpath, and Assistant U.S. Attorney Lydia Gomez-Larsen; the political strategizing between Gomez=Larsen and her boss, U.S. Attorney Buddy Hogan; or the confidential conferences between defendant Moon Hudson and his attorney?

More about Michael Ponsor

U.S. District Judge Michael A. Ponsor, as he is known professionally, presided over a death penalty case in 2001 --- that of Veterans Affairs nurse Kristen Gilbert. Gilbert was convicted of the murders of four veterans under her care by injecting them with lethal doses of epinephrine, but she was spared the death penalty; she is now serving life in prison. As part of his statement upon the conclusion of the case, Ponsor wrote in the traditional legal language (which is certainly more formal than that of his novel): “I take no position on the death penalty per se. Our Constitution gives Congress the duty to weigh the costs and benefits of particular statutes, and I apply them as enacted. Should another capital case come my way, I will again preside, and perhaps find myself with the duty to order a defendant put to death. I accept this.” In writing about THE HANGING JUDGE, Ponsor refers to political theorist Hannah Arendt’s discussion of the evil nature of Adolf Eichmann, Nazi war criminal:

The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal. From the viewpoint of our legal institutions and of our moral standards of judgment, this normality was much more terrifying than all the atrocities put together.

As Ponsor notes in the following Q&A, “The book presents the possibility of a great evil, an innocent man being killed, but the figures in the drama that threaten to commit this evil are mostly very nice, rather funky human beings. This for me is how life works.”

Q: To what extent --- if any --- is Judge Norcross based on you? Is the trial in THE HANGING JUDGE based at all on any case or cases you’ve presided over?

A: The trial is based generally on my experience as a judge, and my experience presiding over a complete death penalty trial. Judge Norcross, however, is not me. He is less experienced than I am as a judge now, and then when I presided over my capital case. He is also, in many ways, a nicer person than I am. What I’ve tried to convey is the sense of moral pressure, emotional pressure, and professional pressure that pervades a proceeding where you are deciding whether a person -‐‐ a live person actually sitting in the same room with you, twenty or thirty feet away --‐ should be deliberately killed. This environment, not particular details of any single case I’ve ever sat on, or specific traits of my own character as a person or a judge, is what I have tried to convey in the book. The consequences of this severe pressure are felt, of course, not only in the courthouse and the courtroom, but outside the formal proceeding in people’s personal lives as well, and I have tried to get that across in crafting the story.

Q: Is fiction writing something you recently became interested in, or is it something you’ve always done in your free time?

A: I’ve been writing fiction for forty years, including several novels or parts of novels. They say it takes 10,000 hours truly to master some skill, whether it is tennis or fiction writing. I have spent far more than 10,000 hours writing fiction, but I am still a long way away from mastering it. Writing does give me great pleasure, and I hope I have acquired some ability at it by now. I certainly enjoy it very much and intend to keep doing it.

Q: How did you first happen upon the case of Dominic Daley and James Halligan? Did you immediately see a parallel between the anti-‐Catholic bias they experienced two centuries ago and biases that are present in some modern courtrooms?

A: The story of Dominic Daley and James Halligan is well known in Western Massachusetts, and in 2006 I participated in commemorations of the 200th anniversary of their tragic executions. The parallels between their case and modern-‐day death penalty cases immediately struck me.

Q: Legal work obviously includes a great deal of writing. Was all the writing you’ve done over the course of your career an asset in completing this novel? Did you have to “unlearn” any legal writing habits as you wrote THE HANGING JUDGE?

A: My legal writing helped to some extent, but was a hindrance in other ways. The exercise of trying to write simply and clearly is shared by legal and fiction writing. A legal writing style, however, can come across as stilted or overly formal in fiction. More importantly, legal writing is not generally as well crafted as publishable fiction. I recently wrote an 80-page opinion in an important piece of litigation before me. It took me about five full days to do it properly, which is a very long time for a trial judge. Given the pressures of a busy docket, we normally do not have that amount of time to devote to one decision. I was only able to do it on this occasion because I was technically "on vacation" and had the undistracted time. On the other hand, eighty pages of publishable fiction, say a novella, would require two or three months of concentrated effort at least, probably more, for the piece to be done even marginally well. As writing, fiction writing is far harder than legal writing, for me at least, but very often more enjoyable.

Q: It is fairly intuitive how you created such authentic characters and dialogue in the courtroom and judge’s chambers. But how did you achieve the same with gang members and their families?

A: I was a criminal defense attorney myself, with some clients not much different from Moon Hudson, before I became a judge. Also, I have visited prisons and participated in many programs that have brought me into contact with many persons charged with crimes and with many convicted criminals. They are actually not that different from the rest of us. I have also spent hundreds of hours reading transcripts and listening to recordings of intercepted phone calls and drug deals where an agent or cooperator was wired, so I have a fair idea of how people talk in these situations.

Q: Did you find your feelings or attitude toward your characters changing as you wrote the novel? Were there any you liked more (or less) at the end than you did at the beginning?

A: Norcross was the most difficult character to draw, paradoxically because he is the most like me. I’m not sure why this is, but it was certainly true. Redpath was the character I came to like and respect the most, although I was fond of all the characters. The book has a couple of what I consider clowns, sort of in the Shakespearean sense, but other than Carlos, who barely appears, there are no real villains in the classic sense. Hannah Arendt apparently said that "the greatest evil is the evil that is committed by no one." Here, the book presents the possibility of a great evil, an innocent man being killed, but the figures in the drama that threaten to commit this evil are mostly very nice, rather funky human beings. This for me is how life works.

Q: Given that capital punishment is such a controversial issue, can readers of all political persuasions enjoy THE HANGING JUDGE? Does the novel take any sort of “position” on the issue?

A: The novel takes no position on the death penalty. It tries only to describe how the process really works, or at least how I have observed it to work. I do believe that it is not possible to have a system of capital punishment without from time to time executing someone who in fact did not commit the crime he or she is being executed for. Human beings, and human-made systems, are fallible. This fact has to be acknowledged in any discussion of capital punishment. Once that fact is recognized, it will then be possible to have an honest discussion about whether the death penalty is worth the cost. The resolution of that discussion is for Congress and the state legislatures, but it must be an honest discussion.