Excerpt

Excerpt

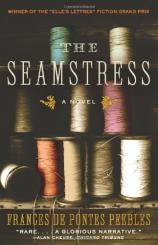

The Seamstress

Recife, Brazil

January 14, 1935

Emília awoke alone. She lay in the massive antique that had once been her mother- in-law’s bridal bed and was now her own. It was the color of burnt sugar with clusters of cashew fruits carved into its giant head- and footboard. The meaty, bell-shaped fruits that emerged from the jacarandá wood looked so smooth and real that, on her first few evenings in this bed, Emília had imagined them ripening overnight — their wooden skins turning pink and yellow, their solid meat becoming soft and fragrant by morning. By the end of her first year in the Coelho house, Emília had given up such childish imaginings.

Outside, it was dark. The street was quiet. The Coelho family’s white house was the largest of all of the newly built estates on Rua Real da Torre, a recently paved road that stretched from the old Capunga Bridge and out into unclaimed swampland. Emília always woke before sunrise, before peddlers invaded Recife’s streets with their creaking carts and their voices that rose to her window like the calls of strange birds. In her old home in the countryside, she’d been accustomed to waking up to roosters, to her aunt Sofia’s whispered prayers, and most of all, to her sister Luzia’s breath, even and hot against her shoulder. As a girl, Emília had disliked sharing a bed with her sister. Luzia was too tall; she kicked open the mosquito net with her long legs. She stole the covers. Their aunt Sofia couldn’t afford to buy them separate beds and insisted it was good to have a sleeping companion — it would teach the girls to occupy little space, to move gently, to sleep silently, preparing them to be good wives.

In the first days of her marriage, Emília had kept to her side of the bed, afraid to move. Degas complained that her skin was too warm, her breathing too loud, her feet too cold. After a week, he’d moved across the hall, back to the snug sheets and narrow mattress of his childhood bed. Emília quickly learned to sleep alone, to sprawl, to take up space. Only one male shared her room and he slept in the corner, in a crib that was quickly becoming too small to hold his growing body. At three years of age, Expedito’s hands and feet nearly touched the crib’s wooden bars. One day, Emília hoped, he would have a real bed in his own room, but not here. Not while they lived in the Coelhos’ house.

The sun rose and the sky lightened. Emília heard shouting in the streets. Six years before, on her first morning in the Coelho house, Emília had trembled and held the bedsheet to her chest until she realized the voices outside the gates were not intruders. They were not calling her name, but the names of fruits and vegetables, baskets and brooms. Each Carnaval, the peddlers’ voices were replaced by the thunderous beating of maracatu drums and the drunken shouts of revelers. Five years earlier, during the first week of October, the peddlers had disappeared completely. Throughout Brazil there were gunshots and calls for a new president. By the next year, things had calmed. The government had changed hands. The peddlers returned. Emília now found comfort in their voices. The men and women sang the names of their wares: "Oranges! Brooms! Alpercata sandals! Belts! Brushes! Needles!" Their voices were strong and cheerful, a relief from the whispers Emília had endured all week. A long, black ribbon hung from the bell attached to the Coelhos’ iron gate. The ribbon warned neighbors, the milkman, the ice wagon, and all delivery boys dropping off flowers and black-bordered condolence cards that this was a house in mourning. The family inside was nurturing its grief, and should not be disturbed by loud noises or unnecessary visits. Those who rang the bell did so tentatively. Some clapped to announce their presence, afraid to touch the black ribbon. The peddlers ignored it. They shouted over the fence, their voices carrying past the massive metal gate, through the Coelho house’s drawn curtains, and into its dark hallways. "Soap! String! Flour! Thread!" The peddlers didn’t concern themselves with death; even grieving people needed the things the peddlers sold, the small necessities of life.

Emília rose from bed.

She slipped a dress over her head but didn’t zip it; the noise might wake Expedito. He lay diagonally across his crib, safely beneath mosquito netting. His forehead shone with sweat. His mouth was set in a tight line. Even in sleep he was a serious child. He’d been that way as an infant, when Emília had discovered him. He’d been skinny and covered in dust. "A foundling," the maids called him. "A child of the backlands." He was born there during the infamous drought of 1932. It was impossible that he would remember his real mother, or those first hard months of his life, but sometimes, when Expedito stared at Emília with his dark, deep-set eyes, he had the stern and knowing look of an old man. Since the funeral he’d often looked at Emília in this way, as if reminding her that they should not linger in the Coelho house. They should travel back to the countryside, for his sake as well as hers. They should deliver a warning. They should fulfill their promise. Emília felt a pinch in her chest. All week she’d felt as if there was a rope within her, stretched from her feet to her head and knotted at her heart. The longer she remained in the Coelho house, the more the knot tightened.

She left the room and zipped up her dress. The fabric gave off a sharp, metallic smell. It had been soaked in a vat of black dye and then dipped in vinegar, to set the new color. The dress had been light blue. It was cut in a modern style with soft, fl uttering sleeves and a slim skirt. Emília had been a trendsetter. Now all of her solid-colored dresses were dyed black and her patterned ones packed away until her year of mourning was officially over. Emília had hidden three dresses and three bolero jackets in a suitcase under her bed. The jackets were heavy; each had a thick wad of bills sewn into its satin lining. Emília had also packed a tiny valise with Expedito’s clothing, shoes, and toys. When they escaped from the Coelho house, she’d have to carry the bags herself. Knowing this, she’d packed only necessities. Before her marriage, Emília had placed too much stock in luxuries. She’d believed that fine possessions had the power to transform; that owning a stylish dress, a gas stove, a tiled kitchen, or an automobile would erase her origins. Such possessions, Emília had thought, would make people look past the calluses on her hands or her rough country manners, and see a lady. After her marriage and her arrival in Recife, Emília discovered this wasn’t true.

Halfway downstairs, she smelled funeral wreaths. The round floral arrangements cluttered the foyer and front hallway. Some were as small as plates, others so large they sat on wooden easels. All were tightly packed with white and purple flowers — gardenias, violets, lilies, roses — and had dark ribbons pinned across their empty centers. Scrawled across the ribbons, painted in gold ink, were the senders’ names and consoling phrases: "Our Deepest Sympathies," "Our Prayers Are with You." The older wreaths were limp, their gardenias yellowed, their lilies shriveled. They gave off a tangy, putrid smell. The air was thick with it.

Emília held the staircase banister. Four weeks ago her husband, Degas, had sat with her on those marble steps. He’d tried to warn her, but she hadn’t listened; Degas had tricked her too many times before. Since his death, Emília spent her days and nights wondering if Degas’ warning hadn’t been a trick at all, but a final attempt at redemption.

Emília walked into the front hall. There was a new wreath, its lilies rigid and thick, their stamens heavy with orange pollen. Emília pitied those lilies. They had no roots, no soil, no way of sustaining themselves, and yet they bloomed. They acted as if they were still fecund and strong when really they were already dead — they just didn’t know it. Emília felt the knot in her chest tighten. Her instincts said Degas had been right, his warning a valid one. And she was like those condolence wreaths, giving him the recognition he so desperately wanted in life but only received in death.

The funeral wreath was a rite unique to Recife. In the countryside it was often too dry to grow flowers. People who died during the rainy months were both blessed and cursed: their bodies decayed faster, and mourners had to pinch their noses during wakes, but there were dahlias, rooster’s crest, and Beneditas bunched into thick bouquets and placed inside the deceased’s funeral hammock before it was carried to town. Emília had attended many funerals. Among them was her mother’s, which she could barely remember. Her father’s funeral occurred later, when Emília was fourteen and Luzia twelve. They lived with their aunt Sofia after that, and though Emília loved her aunt, she couldn’t wait to run away, to live in the capital. As a girl, Emília had always believed that she would leave Sofia and Luzia. Instead, they’d left her.

Emília slipped a black-bordered card from the newest wreath. It was addressed to her father-in-law, Dr. Duarte Coelho. "Grief cannot be measured," the card said. "Neither can our esteem for you. Come back to work soon! From: Your colleagues at the Criminology Institute." The wreaths and cards weren’t meant for Degas. The gifts that arrived at the Coelho house were sent to curry favor with the living. Most of the floral arrangements were from politicians, or from Green Party compatriots, or from underlings in Dr. Duarte’s Criminology Institute. A few of the wreaths were from society women hoping to be in Emília’s good graces. The women had been customers in Emília’s dress shop. They hoped her mourning wouldn’t stifle her dressmaking hobby. Respectable women didn’t have careers, so Emília’s thriving dress shop was considered a diversion, like crochet or charity work. Emília and her sister had been seamstresses. In the countryside, their profession was highly regarded, but in Recife this tier of respectability didn’t exist — a seamstress was the same as a maid or a washerwoman. And to the Coelhos’ dismay, their son had taken up with one. According to the Coelhos, Emília had two saving graces: she was pretty and she had no family. There wouldn’t be parents or siblings clapping at the front gate and asking for handouts. Dr. Duarte and his wife, Dona Dulce, knew Emília had a sister but believed that she — like Emília’s parents and her aunt Sofia — had died. Emília didn’t contradict this belief. As seamstresses, both she and Luzia knew how to cut, how to mend, and how to conceal.

"A great seamstress must be brave." This was what Aunt Sofia used to say. For a long time, Emília disagreed. She believed that bravery involved risk. With sewing, everything was measured, traced, tried on, and revised. The only risk was error. A good seamstress took exact measurements and then, using a sharp pencil, transferred those measurements onto paper. She traced the paper pattern onto cheap muslin, cut out the pieces, and sewed them into a sample garment that her client tried on and which she — the seamstress — pinned and remeasured to correct the flaws in her pattern. The muslin always looked bland and unappealing. At this point, the seamstress had to be enthusiastic, envisioning the garment in a beautiful fabric and convincing the client of her vision. From the pins and markings on the muslin, she revised the paper pattern and traced it onto good fabric: silk, fine-woven linen, or sturdy cotton. Next, she cut. Finally, she sewed those pieces together, ironing after each step in order to have crisp lines and straight seams. There was no bravery in this. There was only patience and meticulousness.

Luzia never made muslins or patterns. She traced her measurements directly onto the final fabric and cut. In Emília’s eyes this wasn’t bravery either — it was skill. Luzia was good at measuring people. She knew exactly where to wind a tape around arms and waists in order to get the most accurate dimensions. But her skill wasn’t dependent on accuracy; Luzia saw beyond numbers. She knew that numbers could lie. Aunt Sofia had taught them that the human body had no straight lines. The measuring tape could miscalculate the curve of a slumped back, the arc of a shoulder, the dip of a waist, the bend of an elbow. Luzia and Emília were taught to be wary of measuring tapes. "Don’t trust a strange tape!" their aunt Sofia often yelled at them. "Trust your own eyes!" So Emília and Luzia learned to see where a garment had to be taken in, let out, lengthened or shortened before they’d even unrolled their measuring tapes. Sewing was a language, their aunt said. It was the language of shapes. A good seamstress could envision a garment encircling a body and see the same garment laid flat on a cutting table, broken into its individual pieces. One rarely resembled the other. When laid flat, the pieces of a garment were odd shapes broken into two halves. Every piece had its opposite, its mirror image.

Unlike Luzia, Emília preferred making paper patterns. She wasn’t as confident at measurement and felt nervous each time she took up her scissors and sliced the final cloth. Cutting was unforgiving. If the pieces of a garment were cut incorrectly, it meant hours of work at the sewing machine. Often these hours were futile — there were some mistakes sewing could never fix.

Emília replaced the condolence card. She walked past the funeral wreaths. At the end of the entrance hall was an easel without flowers propped upon it. Instead, there was a portrait. The Coelhos had commissioned an oil painting for their son’s wake. The Capibaribe River was deep and its currents strong, but police had managed to find Degas’ body. It had been too bloated to have an open casket during the wake, so Dr. Duarte had a portrait of his son made instead. In the portrait, Emília’s husband was smiling, thin, and confident — all of the things he’d never been in life. The only aspect the painter had gotten right was Degas’ hands. They had tapered fingers and buff ed, immaculate nails. Degas had been stout, with a thick neck and wide fleshy arms, but his hands were slender, almost womanly. Emília wished she’d noticed this the minute she’d met him.

Police deemed Degas’ death an accident. The officers were loyal to Dr. Duarte because he’d founded the state’s first Criminology Institute. Recife, however, was a city that prized scandal. Accidents were dull, blame interesting. During the wake, Emília had heard mourners whispering. They tried to root out the responsible parties: the car, the rainstorm, the slick bridge, the rough waters of the river, or Degas himself, alone at the wheel of his Chrysler Imperial. Dona Dulce — Emília’s mother- in-law — insisted on the police’s version of events. She knew that her son had lied, saying he was going to his office to pick up papers related to an upcoming business trip, the first such trip Degas had ever taken. He never went to his office. Instead he drove aimlessly around the city. Dona Dulce did not blame Emília for Degas’ death; she blamed her daughter-in-law for the aimlessness that had caused it. A proper wife — a well-bred city girl — would have cured Degas’ weaknesses and given him a child. Dr. Duarte was more sympathetic toward Emília. Her father-in-law had arranged Degas’ so-called business trip. Without Dona Dulce’s knowledge, Dr. Duarte had reserved a spot for their son at the prestigious Pinel Sanitorium in São Paulo. Dr. Duarte had believed that the clinic’s electric baths would accomplish what marriage and self-discipline had not.

Emília stepped closer to the portrait, as if proximity would make its subject more familiar. She was twenty-five years old and already a widow, mourning a husband she hadn’t understood. At times, she’d hated him. Other times, she’d felt an unexpected kinship with Degas. Emília knew how it felt to love what was prohibited, and to deny that love, to betray it. That kind of emotion was a burden — a weight so heavy it could drag a person to the bottom of the Capibaribe River and keep him there.

She’d been sloppy with her life. She’d been so eager to leave the countryside that she’d chosen Degas without studying him, without measuring him. In the years since her escape, she’d tried to fix the mistakes inherent in her hasty beginning. But some things weren’t worth fixing. When she realized this, Emília finally understood what Aunt Sofia had meant about bravery. Any seamstress could be meticulous. Novice and expert alike could fuss over measurements and pattern drawings, but precision didn’t guarantee success. An unskilled seamstress delivered poorly sewn clothes without trying to hide the mistakes. Good seamstresses felt an attachment to their projects and spent days trying to fix them. Great ones didn’t do this. They were brave enough to start over. To admit they’d been wrong, throw away their doomed attempts, and begin again.

Emília stepped away from Degas’ funeral portrait. In bare feet, she padded out of the hall and into the Coelho house’s courtyard. At the center of the fern-lined patio stood a fountain. A mythical creature — half horse, half fish — spat water from its copper mouth. Across the courtyard, the glass-paneled dining room doors were propped open. The curtains across the entrance were closed, shifting with the breeze. Behind them, Emília heard Dona Dulce. Her mother- in-law spoke sternly to a maid, telling her to set the table correctly. Dr. Duarte complained that his newspaper was late. Like Emília, he was always anxious for the newspaper.

On the right end of the courtyard were doors that led to Dr. Duarte’s study. Emília walked quickly toward them, careful not to trip over the jabotis. The turtles always scuttled in the courtyard. They were family heirlooms, each fifty years old and purchased by her husband’s grandfather. The turtles were the only animals allowed in the Coelho house and they were content with bumping up against the glazed tile walls of the courtyard, hiding among the ferns and eating scraps of fruit the maids brought them. Emília and Expedito liked to pick them up when no one was looking. They were heavy things; she had to use both hands. The turtles’ wrinkled limbs flapped wildly each time Emília held them, and when she tried to stroke their faces they snapped at her fingers. The only parts of them she could touch were their shells, which were thick and unfeeling, like the turtles themselves.

In the countryside she’d been surrounded by animals. There were lizards in the dry summer months and toads in the winter. There were hummingbirds and centipedes and stray cats that begged for milk at the back door. Aunt Sofia raised chickens and goats, but those were destined for the dinner table, so Emília never got friendly with them. But Emília used to have three singing birds in wooden cages. Every morning after she fed them, she would put her finger through the cage’s bars and allow the birds to pick under her fingernails. "Those birds were tricked," her sister Luzia said every time she saw Emília feeding them. "You should let them go." Luzia disliked the way they’d been caught. Local boys would put a bit of melon or pumpkin in cages and lay in wait, latching the cage’s doors as soon as a bird hopped inside. Then the boys sold those red-beaked finches and tiny canaries at the weekly market. When the wild birds got wise to the boys’ trick and avoided the food inside the empty cages, the bird catchers used another strategy — one that never failed. They tied a tame bird inside the cage to make the wild ones believe it was safe. One bird unknowingly lured the other.

In his study, Emília’s father-in law had an orange-winged corrupião that he’d trained to sing the first strophe of the national anthem. There was always a great racket in the Coelhos’ kitchen where Emília’s mother- in-law commanded her legion of maids in making jams and cheeses and sweetmeats. But sometimes, under the noise, Emília could hear the corrupião singing the somber notes of the anthem, like a ghost calling from within the walls.

The bird chirped when Emília eased the study doors open. The corrupião sat in a brass cage in the middle of Dr. Duarte’s office, among his phrenological charts, his collection of pickled and colorless organs floating in glass jars, and his row of porcelain skulls with their brains categorized and numbered. Emília’s underarms were wet. She smelled something sour, and was unsure if the scent came from her dyed dress or from her own sweat. Dr. Duarte didn’t allow people in his study uninvited — not even maids. If caught, Emília would say she was checking on the corrupião. She ignored the bird and went to Dr. Duarte’s desk. On it were stacks of unanswered condolence cards. There were papers listing the cranial measurements of all detainees at the Downtown Detention Center. There was the handwritten draft of a speech Dr. Duarte would give at the end of the month. Words were crossed out. The speech’s conclusion was blank; Dr. Duarte hadn’t yet obtained his prize specimen, the female criminal whose cranial measurements would confirm his theories and conclude his lecture. Emília flipped though piles of papers. There was nothing resembling a bill of sale. There were no customs forms, no train logs, no dated evidence of an unusual shipment to Brazil. She looked for words written in a foreign tongue, knowing she would recognize one in particular: Bergmann. The name was the same in German as in Portuguese.

Emília found only newspaper clippings. She had a similar collection, locked in her jewelry box so the Coelho maids couldn’t find hem. Some articles were yellowed by years of exposure to Recife’s humidity. Some still smelled of ink. All centered on the brutal cangaceiro Antônio Teixeira — nicknamed the Hawk because of his penchant for plucking out the eyes of his victims — and his wife, called the Seamstress. They were not fugitives because they had never been caught. They were not outlaws because the countryside had no laws, not until recently, when President Gomes had tried to implement his own. The definition of a cangaceiro depended on who was asked. To tenant farmers, they were heroes and protectors. To vaqueiros and merchants, they were thieves. To farm girls, they were fine dancers and romantic heroes. To the mothers of those girls, cangaceiros were defilers and devils. Schoolchildren, who often played cangaceiros versus police, fought for the roles of cangaceiros even though their teachers scolded them for it. Finally, to the colonels — the largest landowners in the countryside — cangaceiros were an inevitable nuisance, like the droughts that killed cotton crops, or the deadly brucellosis that infected cattle. Cangaceiros were blights that the colonels and their fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers before them had had to withstand. Cangaceiros lived like nomads in the scrubland’s thorny wilderness, stealing cattle and goats, raiding towns, exacting revenge on enemies. They were men who could not be frightened into obedience or whipped into submission.

The Hawk and the Seamstress were a new breed of cangaceiro. They knew how to read and write. They dispatched telegrams to the Diário de Pernambuco newspaper offices and even sent personal notes to the governor and the president, which newspapers photographed and reprinted. The notes were written on fine linen paper, with the outlaw’s seal — a large letter H — embossed on the top. In them, the Hawk condemned the government’s roadway project, the Trans-Nordestino Highway, and vowed to attack all construction sites in the scrub. The Hawk insisted he was no lowly goat thief; he was a leader. He offered to divide the state of Pernambuco, leaving the coast to the republic and the countryside to the cangaceiros. Emília studied the Hawk’s penmanship. It was feminine in its curling script, much like the cursive that Padre Otto, the German immigrant priest who ran her old grade school, had taught her and Luzia as children.

Reports said that the Hawk’s group numbered between twenty and fifty well-armed men and women. The leading female, the Seamstress, was famous for her brutality, for her talent with a gun, and for her looks. She was not attractive, but was so tall that she stood above most of the men. And she had a crippled arm, bent permanently at the elbow. No one knew where the name the Seamstress had come from. Some said it was because of her precise aim; the Seamstress could fill a man with holes, just like a sewing machine poked cloth with its needle. Others said she really knew how to sew and that she was responsible for the cangacieros’ elaborate uniforms. The Diário had printed the only photo of the group; Emília kept a copy of it in her jewelry box. The cangaceiros wore well-tailored jackets and pants. Their hats had the brims cracked and upturned, resembling half-moons. Everything the cangaceiros carried — from their thick-strapped bornal bags to their cartridge belts — was elaborately decorated with stars, circles, and other indecipherable symbols. Their clothes were heavily embroidered. Their leather rifle straps were tooled and studded. To Emília, the cangaceiros looked both splendid and ridiculous.

The final theory about the Seamstress’s name was the only one Emília believed. They called that tall, crippled woman the Seamstress because she held her cangaceiro group together. Despite the drought of 1932, despite President Gomes’s efforts to exterminate the group, despite the Criminology Institute’s cash rewards in exchange for the bandits’ heads, the cangaceiros had survived. They even accepted women into their ranks. Many attributed this success to the Seamstress. There were theories — unproven but persistent — that the Hawk had died. The Seamstress had planned all of the roadway attacks. She had written the letters addressed to the president. She had sent telegrams bearing the Hawk’s name. Most politicians, police, and even President Gomes himself deemed this theory impossible. The Seamstress was tall, callous, and perverse but she was still a woman.

Emília searched the final stack of papers on her father-in-law’s desk. Newspaper clippings stuck to her sweaty palms. She shook them off. She’d never understood the Seamstress’s behavior, but Emília admired the cangaceira’s boldness, her strength. In the days after Degas’ death, she’d prayed for those attributes.

Within the Coelho house, a bell chimed. Breakfast was served. Emília’s mother- in-law kept a brass bell beside her chair in the dining room. She used it to call servants and to indicate mealtimes. The bell rang a second time; Dona Dulce disliked stragglers. Emília straightened the papers on her father-in-law’s desk and left.

She sat in her designated place at the far end of the dining table, removed from its other occupants. Her father-in-law sat at the head, sipping coffee from his porcelain cup and unwrapping his newspaper. Emília’s mother- in-law sat beside him, pale and rigid in her mourning dress. Between them was an empty chair, its back covered in a black cloth, where Emília’s husband had sat. Degas’ place was neatly set with the Coelhos’ blue-and-white china, as if Dona Dulce expected her son to return. Emília stared at her own place setting. There were too many utensils to navigate. There was a medium-size spoon to mix her coffee, a larger spoon for her cornmeal, a tiny spoon for jam, and an array of forks for eggs and fried bananas. Years ago, during her first weeks with the Coelhos, Emília hadn’t known which utensil was which. She didn’t dare guess, either, with her mother- in-law scrutinizing her from across the table. There was no need for such complications, such finery in the morning, and in her first months at the Coelho table Emília believed her mother- in-law set the elaborate table just to confuse her.

Emília ignored the plate of eggs and the steaming mound of cornmeal at the center of the table. She sipped coffee. Near her, Dr. Duarte held up his newspaper and smiled. His teeth were wide and yellow.

"Look!" he shouted, shaking the Diário de Pernambuco’s pages. The paper’s headline fluttered before Emília’s eyes.

Raid on Cangaceiros Successful! Seamstress & Hawk Believed Dead! Heads Transported to Recife.

Emília stood. She walked to the head of the table.

The article said that the president of the republic would not tolerate anarchy. That troops were sent into the backlands equipped with their new weapon, the Bergmann machine gun. The gun was a modern marvel, spitting out five hundred rounds per minute. It had been imported from Germany by Coelho & Son, Ltd., the import-export firm owned by renowned criminologist Dr. Duarte Coelho and his recently deceased son, Degas. The shipment of Bergmanns had arrived in secret, earlier than anyone had expected. The article reported that, before the ambush, the cangaceiros had looted and burned a highway construction site. They had raided a town. Eyewitnesses — tenant farmers and the local accordion player — said that the outlaws had rightfully purchased a case of Fleur d’Amour toilet water and had thrown gold coins to children in the streets. They said that the cangaceiros had attended mass and had even gone to confession. Then the Seamstress and the Hawk took their cangaceiros to the São Francisco River, to lodge on a doctor’s ranch. Once a trusted friend of the cangaceiros, the doctor had secretly sided with the state and telegrammed nearby troops to inform them of the Hawk’s presence. The bird is home, the doctor wrote in his message.

The cangaceiros were camped in a dry gulley when government troops invaded. It was dark, which made it hard to aim. But with their new Bergmann guns, the troops didn’t have to. They easily hit their marks. The next morning a vaqueiro, who was releasing his herd at dawn, said he’d witnessed a few cangaceiros escaping from their battle with the troops. He claimed he saw a small group of individuals — all wearing the cangacieros’ distinctive leather hats, their brims flipped up in the shape of a half-moon — limping across the state border. But police officials proclaimed that the outlaws were all dead, shot down and decapitated, even the Seamstress.

Emília read the article’s last line and did not feel the porcelain coffee cup slip from her hands and break into bits against the slate floor. She did not feel the burning liquid splash onto her ankles, did not hear her mother- in-law gasp and exclaim that she had no manners, did not see the maid crawl beneath the veined marble table to pick up the mess.

Emília rushed up the tiled staircase to her bedroom — the last room at the end of the carpeted and musty hallway. Expedito was there. He sat on Emília’s bed while the nanny combed his wet hair. Emília dismissed the woman. She lifted her boy from the bed. When he squirmed in her tight embrace, Emília released him. She pulled a polished wooden box from beneath the bed. Emília unclasped the gold chain around her neck and used the small brass key that dangled from it to open the box’s lock. Inside was a velvet-lined tray, empty except for a ring and a pearl necklace. Degas had bought her the largest jewelry box he could find, promising to fill it. Emília lifted the tray. In the deep space beneath it — a place meant to hold pendants, or tiaras, or thick bracelets — was Emília’s collection of newspaper articles, bound with a blue ribbon. Beneath those was a small framed photograph. Two girls stood side by side. Both wore white dresses. Both held Bibles. One girl smiled widely. Her eyes, however, did not match her mouth’s rigid happiness. They looked anxious, expectant. The other girl had moved when the picture was taken, and so she was blurred. Unless one looked closely, unless one knew her, you could not tell exactly who she was.

Emília had cradled this communion portrait in her arms as she rode on horseback out of her hometown of Taquaritinga. She’d held it in her lap during the bumping train ride to Recife. In the Coelho house, she’d placed it in her jewelry box, the only place the Coelho maids were prohibited from probing.

Emília knelt beside the portrait. Her boy copied her, clasping his hands firmly to his chest as Emília had taught him. He stared at her. In the morning sunlight, his eyes were not as dark as they sometimes seemed — within the brown were specks of green. Emília bowed her head.

She prayed to Santa Luzia, the patron saint of the eyes, her sister’s namesake and protector. She prayed to the Virgin, the great guardian of women. And she prayed most fervently to Saint Expedito, the answerer of all impossible requests.

Emília had given up many of her old, foolish beliefs in this house — a place where her husband had not been her husband but some stranger she did not care to know, where maids were not maids but spies for her mother- in-law, where fruits were not fruits but wood, polished and dead. But Emília still believed in the saints. She believed in their powers. Expedito had brought her sister back from death once. He could do it again.

The Seamstress

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 656 pages

- Publisher: Harper Perennial

- ISBN-10: 006073888X

- ISBN-13: 9780060738884