Excerpt

Excerpt

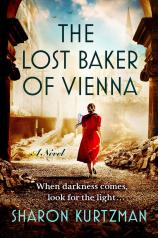

The Lost Baker of Vienna

Munich, Germany to Vienna, Austria

March 1946

At the Munich train station, Chana Rosenzweig pushed a strand of blond hair off her forehead and held tight to her younger, teenage brother’s hand. It was impossible to tell whose palm was sweatier. Their mother was on his other side, her arm linked through his, her expression hard and impenetrable as usual.

It was strange to be out in the world this way. Moving around freely with no one in charge of you, threatening you, pointing a gun at you.

“It will be good, you’ll see,” she said to Aron.

“I know. We’ll be together,” he said.

“Always.” With two fingers, she tapped her chest twice, right over her heart.

He did the same. It was how they conveyed I love you without words. During months spent hiding in an attic after the Nazis liquidated the Vilna ghetto, silence saved their lives.

Chana wondered how they looked to the other passengers, gaunt as they were and dressed plainly, but neatly. Both she and their mother, Ruth, wore dark wool skirts, sturdy black boots, and white blouses under their coats; the same garments distributed upon entry to every woman housed in Foehrenwald. Aron wore dark pants and a gray sweater and kept his head down.

The station smelled mostly of fumes, soot, and people. Then Chana caught a whiff of perfume as she passed a well-heeled woman in a fur coat. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d inhaled something so lovely.

As they found the train to Wien, Chana was grateful to at last be free from Foehrenwald. After the war, Chana and her family, like many surviving Jews, took shelter in displaced persons camps because they had nowhere else to go. Their homes had either been destroyed by bombs or taken over by locals. Even if her family’s home had been empty, Chana’s mother refused to live beside neighbors who’d abused them, or in the country that had oppressed them. But they weren’t free to go just anywhere. DP camp officials distributed no traveling papers, trapping refugees like Chana, her mother, and brother. They were a forgotten lot.

For months in Foehrenwald, Chana had heard whispers about a group of men organizing these escapes. They called themselves Brihah, and she learned their aim was to smuggle Jewish refugees out of Europe.

“They’re former resistance fighters,” some said.

“They’re exsoldiers from Britain’s Jewish Brigade,” others claimed.

She heard most of those smuggled out were on their way to Palestine, though some headed to Canada or America. All traveled illegally, violating those countries’ immigration quotas.

For this trip, Chana and her family had been instructed to stay together, but to ignore the others in their group. From the corner of her eye, Chana caught sight of a scattered baker’s dozen, those they’d traveled with on the back of a truck, all on the same clandestine trip. A few she knew from Foehrenwald—like her friend Shifra. Others Chana had never seen before. From the bits they’d shared on the ride to the Munich train station, she’d learned they were all Jewish refugees fleeing Europe. They couldn’t appear to be traveling as a large group; it could draw the scrutiny of their forged papers. If they were discovered, they’d be sent back to the DP camp.

A loud whistle blew. Now Chana, Aron, and their mother boarded the train for Wien and found adjoining seats. Chana forced a smile, pretending ease, while her nerves skittered around her chest. She tried to call upon the confidence she’d used delivering messages for the Vilna ghetto’s resistance.

She remembered the day Natan had recruited her.

“You look Aryan,” Natan had said. “It’s the perfect disguise.”

Chana had jumped at the chance to fight back. Papa had long been involved with Vilna’s resistance, mainly smuggling in food for the starving population.

Chana’s task was to deliver books with hidden messages, first to locations within the ghetto, then beyond the wood-planked gate and barbed-wire fence into the gentile section of the city, where some partisans hid. Natan gave her the code name “Wren” because of the songbird’s ability to survive in a variety of habitats. Every time she went out, she had to pretend she belonged, yet be invisible. Somehow, she’d managed it.

The train jerked, and panic washed over her. During the war, she’d stood in packed cattle cars, hurtling between places. Never knowing what she would meet when she arrived. Work? Death? Would she ever be able to go through daily life without reminders of all that she’d suffered?

She told herself that the thin-padded seat where she now sat was a luxury compared to what she’d once endured. Aron was beside her, his face ashen. Their mother stared off, lost in her own world.

“Chana,” Aron whispered.

“Shhh, it’s okay.” She bent close. “Remember, we’re on our way to Vienna. Someplace good. Take my hand.” He hesitated. At fifteen, he often shrugged off her attempts to baby him. Finally, he grabbed her hand. “Breathe with me,” she said, inhaling and exhaling. He followed, and the steady rhythm soothed them both.

Excerpted from THE LOST BAKER OF VIENNA. © Copyright 2025, Sharon Kurtzman. All rights reserved.

The Lost Baker of Vienna

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- hardcover: 432 pages

- Publisher: Pamela Dorman Books

- ISBN-10: 0593830865

- ISBN-13: 9780593830864