Excerpt

Excerpt

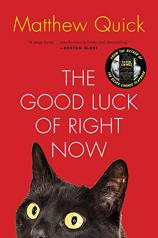

The Good Luck of Right Now

If you want others to be happy, practice compassion. If you want to be happy, practice compassion.

— The Dalai Lama

Certainly there have been better actors than me who have had no careers. Why? I don’t know.

— Richard Gere

1

The You-Me Richard Gere of Pretending

Dear Mr. Richard Gere,

In Mom’s underwear drawer—as I was separating her “personal” clothes from the “lightly used” articles I could donate to the local thrift shop—I found a letter you wrote.

As you will recall, your letter was about the 2008 Olympics held in Beijing, China—you were advocating for a boycott because of the crimes and atrocities the Chinese government committed against Tibet.

Don’t worry.

I’m not one of those “crazy types.”

I immediately realized that this was a form letter you sent out to millions of people through your charitable organization, but Mom was a good enough pretender to believe you had personally signed the letter specifically to her, which is most likely why she saved it—believing you had touched the paper with your hands, licked the envelope with your tongue—imagining the paper represented a tangible link to you . . . that maybe a few of your cells, microscopic bits of your DNA, were with her whenever she held the letter and envelope.

Mom was your biggest fan, and a seasoned pretender.

“There’s his name written in cursive,” I remember her saying to me, poking the paper with her index finger. “From Richard Gere! Movie star RICHARD GERE! ”

Mom liked to celebrate the little things. Like finding a forgotten wrinkled dollar in a lint-ridden coat pocket, or when there was no line at the post office and the stamp sellers were up for smiles and polite conversation, or when it was cool enough to sit out back during a hot summer—when the temperature dips dramatically at night even though the weatherman has predicted unbearable humidity and heat, and therefore the evening becomes an unexpected gift.

“Come enjoy the strange cool air, Bartholomew,” Mom would say, and we’d sit outside and smile at each other like we’d won the lottery.

Mom could make small things seem miraculous. That was her talent.

Richard Gere, perhaps you have already labeled Mom as weird, pixilated—most people did.

Before she got sick, she never gained or lost weight; she never purchased new clothes for herself, and therefore was perpetually stuck in mideighties fashions; she smelled like the mothballs she kept in her drawers and closet, and her hair was usually flattened on the side she rested against her pillow (almost always the left).

Mom didn’t know that computer printers could easily reproduce signatures, because she was too old to have ever employed modern technology. Toward the end, she used to say that “computers were condemned by the Book of Revelations,” but Father McNamee told me it’s not true, although we could let Mom believe it was.

I’d never seen her so happy as she was the day your letter arrived.

As you might have gathered, Mom wasn’t all there during the last few years of her life, and by the very end extreme dementia had set in, which made it hard to distinguish the pretending of her final days from the real world.

Everything blurred over time.

During her good moments—if you can believe it—she actually used to think (pretend?) that I was you, that Richard Gere was living with her, taking care of her, which must have been a welcome alternative to the truth: that her ordinary unaccomplished son was her primary caregiver.

“What will we be having for dinner tonight, Richard?”she’d say. “Such a pleasure to finally spend so much time with you, Richard.”

It was like when I was a boy and we’d pretend we were eating dinner with a famous guest—Ronald Reagan, Saint Francis, Mickey Mouse, Ed McMahon, Mary Lou Retton—occupying one of the two seats in the kitchenthat were always empty, except when Father McNamee visited.

As I previously stated, Mom was quite a fan of yours—you probably visited our kitchen table before, but to be honest, I don’t remember a specific Richard Gere visit from childhood. Regardless, I indulged her and played my role, so you were manifested through me, even though I’m not as

handsome, and therefore made a poor stand-in. I hope you don’t mind my having invoked you without your permission. It was a simple thing that gave Mom great pleasure. Her face lit up like the Wanamaker’s Christmas Light Show every time you came to visit. And after the failed chemo and brain surgery, and the awful sick, retching aftermath, it was hard to get her to smile or be happy about anything, which is why I went along with the game of you and me becoming we.

It started one night after we watched our well-worn VCR copy of Pretty Woman, one of Mom’s favorite movies.

As the end credits rolled, she patted my arm and said, “I’m going to bed now, Richard.”

I looked at her, and she smiled almost mischievously—like I’d seen the sexy fast girls do with their shiny painted lips back when I was in high school. That salacious smile made me feel nauseated, because I knew it meant trouble. It was so unlike Mom too. It was the beginning of living with a stranger.

I said, “Why did you call me Richard?”

She laid her hand gently on my thigh, and in this very flirtatious girlish voice, while batting her eyelids, she said, “Because that’s your name, silly.”

During the thirty-eight years we had known each other, Mom had never once before called me “silly.”

The tiny angry man in my stomach pounded my liver with his fists.

I knew we were in trouble.

“Mom, it’s me—Bartholomew. Your only son.”

When I looked into her eyes, she didn’t seem to see me. It was like she was having a vision—seeing what I could not.

It made me wonder if Mom had used some sort of womanly witchcraft and turned me into you somehow.

That we—you and me—had become one in her mind.

Richard Gere.

Bartholomew Neil.

We.

Mom took her hand off my thigh and said, “You’re a handsome man, Richard, the love of my life even, but I’m not going to make the same mistake twice. You made your choice, so you’ll just have to sleep on the couch. See you in the morning.” Then she floated up the stairs, moving quicker than she had in months.

She looked ecstatic.

Like the haloed saints depicted in stained glass at Saint Gabriel’s, Mom seemed to be guided by divinity. Her madness appeared holy. She was bathed in light.

As uncomfortable as that exchange was, I liked seeing Mom lit up. Happy. And pretending has always been easy for me. I have pretended my entire life. Plus there was the game from my childhood, so I had certainly practiced.

Somehow—because who can say exactly how these things come to be—over many days and weeks, Mom and I slipped into a routine.

We both began pretending.

She pretended I was you, Richard Gere.

I pretended Mom wasn’t losing her mind.

I pretended she wasn’t going to die.

I pretended I wouldn’t have to figure out life without her.

Things escalated, as they say.

By the time she was confined to the pullout bed in the living room with a morphine pain pump spiking her arm, I was playing you twenty-four hours a day, even when Mom was unconscious, because it helped me, as I faithfully pushed the button every time she grimaced.

To her I was no longer Bartholomew, but Richard.

So I decided I would indeed be Richard and give Bartholomew some well-deserved time off, if that makes any sense to you, Mr. Gere. Bartholomew had been working overtime as his mother’s son for almost four decades. Bartholomew had been emotionally skinned alive, beheaded, and crucified upside down, just like his apostle namesake, according to various legends, only metaphorically—and in the modern world of today and right now.

Being Richard Gere was like pushing my own mental morphine pain pump.

I was a better man when I was you—more confident, more in control, surer of myself than I have ever been.

The hospice workers went along with my ruse. I firmly instructed them to call me Richard whenever we were in the room with Mom. They looked at me like I was crazy, but they did as I asked, because they were hired help.

Hospice workers took care of Mom only because they were being paid. I wasn’t under any illusion that these people cared about us. They glanced at their cell phone clocks fifty times an hour and always looked so relieved when they put on their coats at the end of their shifts—like departing from us was akin to attending a wonderful party, like walking out of a morgue and into the Oscars.

When Mom was sleeping, the hospice workers sometimes called me Mr. Neil, but whenever she was awake I was you, Richard, and they were doing as I asked because of the money they were being paid by the insurance company. They even used a very formal, reverent tone when they addressed us. “Can we do anything to make your mother more comfortable, Richard?” they’d say whenever she was awake, although they never once called me Mr. Gere, which was okay with me, since you and Mom were on a first-name basis from the start.

I want you to know that Mom truly loved watching the Olympics. She never missed the games—she used to watch with her mother too—and watching gave her such great pleasure, maybe because she never left the Philadelphia area during her seventy-one years on earth. She used to say that watching the Olympics was like taking a foreign vacation every four years, even after they switched the winter and summer games to different years, and therefore the Olympics occurred every two years, which I’m sure you know already.

(Sorry for being redundant, but I am writing to you as Bartholomew Neil—unlike

you in every way imaginable. I hope you will bear with me and forgive me my common-ness. I am not pretending to be Richard Gere at the time of writing. I am much more eloquent when I am you. MUCH. Bartholomew Neil is no movie star; Bartholomew Neil has never had sex with a supermodel; Bartholomew Neil never even escaped the city in which you and I were born, Richard Gere, the City of Brotherly Love; Bartholomew Neil is sadly intimate with these facts. And Bartholomew Neil is not much of a writer either, which you have already surmised.)

Mom loved gymnastics, especially the triangle-torsoed men, who “moved like warrior angels.” She clapped until her palms were pink whenever someone did the iron cross on the rings. That was her favorite. “Strong as Jesus on his worst day,” she’d say. And she even watched the opening and closing ceremonies—every second. Every Olympic event they televised, Mom watched.

But when she received your letter—the one I mentioned earlier, outlining the atrocities committed against Tibet by the Chinese government—she decided not to watch the Olympics set in China, which was a great sacrifice for her.

“Richard Gere is right! We should be sending the People’s Republic of China a message! Horrible! What they are doing to the Tibetan people. Why doesn’t anyone care about basic human rights?” Mom said.

I must admit that—being far more pessimistic, resigned, and apathetic than Mom ever was— I argued futilely for watching the Olympics. (Please forgive me, Mr. Gere. I had little faith back then.) I said that our watching or not watching wouldn’t even be documented, let alone have any impact on foreign relations whatsoever—“China won’t even know we aren’t watching! Our boycott will be pointless!” I protested—but Mom believed in you and your cause, Mr. Gere. She did what you asked, because she loved you and had the faith of a child.

This meant I did not get to see the Olympics either, and I was initially perturbed, as this was a traditional mother-son activity in the Neil household, but I got over that long ago. Now I am wondering if Mom’s boycott, her death, and my finding the letter you wrote her—maybe these things mean you and I are meant to be linked in some important cosmic way.

Maybe you are meant to help me, Richard Gere, now that Mom is gone.

Maybe this is all part of her vision—her faith coming to fruition.

Maybe you, Richard Gere, are Mom’s legacy to me!

Perhaps you and I are truly meant to become WE.

To further prove the synchronicity of all this (have you read Jung? I actually have. Are you surprised?), Mom booed the Chinese unmercifully at the 2010 Vancouver games—even the jumping and pirouetting Chinese figure skaters, who were so graceful—which was just before I began to notice the dementia, if memory serves.

It didn’t happen all at once, but started with little things like forgetting names of people we saw on our daily errands, leaving the oven on overnight, forgetting what day it was, getting lost in the neighborhood where she lived her entire life, and misplacing her glasses repetitively, often on the top of her head—small everyday lapses.

(She never forgot you, though, Richard Gere. She talked to you-me daily. Another sign. Never once did she forget the name Richard.)

To be honest, I’m not really sure when her mental decline began, as I pretended not to notice for a long time. I’ve never been particularly good with change. And I didn’t think of giving in to Mom’s madness and being you until much later. I am slow to the dance, always late for the cosmic ball, as wiser people like you undoubtedly say.

The doctors told me that it wasn’t our fault, that even if we had brought Mom to them earlier, things would have most likely ended up the same way. They said this to us when we got agitated at the hospital, when they wouldn’t let us in to see Mom after her operation and we started yelling.

A social worker spoke with us in a private room while we waited for permission to see our mother. And when we saw her, her head bandages made her look mummified and her skin looked sickness yellow and it was just so plain horrible, and—based on the concerned looks the hospital staff were giving us—we were visibly terrified.

On our behalf, the social worker asked the doctors whether we could have done anything more to prevent the cancer from growing—had we been negligent? That’s when the doctors told us that it wasn’t our fault, even though we’d ignored the symptoms for months, pretending away the problems of our lives.

Even still.

It wasn’t our fault.

I hope you will believe me, Richard Gere.

It wasn’t my fault, nor was it yours.

You sent only one letter, but you were with Mom to the end—in her underwear drawer, and by her side through me, your medium, your incarnation.

The doctors repeatedly confirmed that fact—that we couldn’t have done anything more.

The squidlike brain tumor that had sent its tentacles deep into our mother’s mind was not something we could have predicted or defeated, the doctors told us multiple times, in simple straightforward language that even men of lesser intelligence could easily grasp.

It wasn’t our fault, Richard Gere.

We did everything we could have done, including the pretending, but some forces are too powerful for mere men, which the social worker at the hospital confirmed with a reluctant and sad nod.

“Not even a famous actor like Richard Gere could have secured better care for his mother,” that social worker answered when I brought you up—when I shared my worry of being a failure at life, not even able to take care of his only mother, which was his one job in the world, the only purpose he had ever known.

Miserable failure! the tiny man in my stomach screamed at me. Retard! Moron!

The brain-cancer squid ended our mother’s life only a few weeks or so ago, a short long blur (that stretches and shrinks in my memory) after surgery and chemo failed to heal her.

The doctors stopped treating her.

They said to us—“This is the end. We are sorry. Try to keep her comfortable. Make the most of your time. Say your good-byes.”

“Richard?” Mom whispered to me on the night she died.

That’s all.

One.

Single.

Word.

Richard?

The question mark was audible.

The question mark haunts me.

The question mark made me believe that her whole life could be summed up by punctuation.

I wasn’t upset, because Mom had said her last word to the you-me Richard Gere of pretending, which included me—her flesh-and- blood son—too.

I was Richard at that moment.

In her mind, and in my own.

Pretending can help in so many ways.

Now we hear birds chirping in the morning when we sit alone in the kitchen drinking coffee, even though it is winter. (These must be either tough, hardy city birds unafraid of low temperatures, or birds too lazy to migrate.) Mom always had the TV blaring because she liked to “listen to people talk,” so we never knew about the birds chirping before. Thirty-nine years in this house, and this is the first time we ever heard birds chirping in the morning sunlight while we drank our coffee in the kitchen.

A symphony of birds.

Have you ever really listened to birds chirping—really truly listened?

So pretty it makes your chest ache.

My grief counselor Wendy says I need to work on being more social and forming a “support group” of friends. She was here in my kitchen once when the morning birds were chirping and Wendy paused midsentence, cocked her ear toward the window, squinted her eyes, and wrinkled her nose.

Then she said, “Hear that?”

I nodded.

A cocky smile bloomed just before she said—as only someone so young could—in this upbeat cheerleader voice, “They like being together in a flock. Hear how happy they are? How joyful? You need to find your flock now. Finally leave the nest, so to speak. Fly even. Fly! There’s a lot of sky out there for brave birds. Do you want to fly, Bartholomew? Do you? ”

She said all of those words quickly, so that she was out of breath by the time she finished her cheery cheer. Her face was flushed robin’s-breast red, like it gets whenever she’s making what she considers to be a remarkably extraordinary point. She looked at me wide-eyed—“kaleidoscope eyes,” the Beatles sing—and I knew the response to her call, what I was supposed to say, what would make her so happy, what would validate her existence in my kitchen and make her feel as though her efforts mattered, but I couldn’t say it.

I just couldn’t.

It took a lot of effort to remain calm, because part of me—the evil black core of me where the tiny angry man lives—wanted to grab Wendy’s birdlike shoulders and shake all of the freckles off her beautiful young face while I screamed at her, yelling with a force mighty enough to blow back her hair, “I am your elder! Respect me!”

“Bartholomew?” she said, looking up from under her thin orange eyebrows, which are the color of crunchy sidewalk leaves.

“I am not a bird,” I told her in the calmest voice available to me at that time, and stared fiercely at my brown shoelaces, trying to remain still.

I am not a bird, Richard Gere.

You know this already, I know, because you are a wise man.

Not a bird.

Not a bird.

Not.

A.

Bird.

Your admiring fan,

Bartholomew Neil