Excerpt

Excerpt

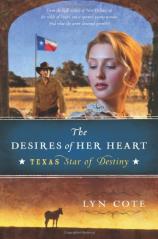

The Desires of Her Heart: Texas Star of Destiny, Book 1

One

Belle Vista Plantation

New Orleans, late August 1821

“You wish to marry well? By that, Jewell, you mean marry a wealthy man?” Dorritt sat in her stepfather’s lavish ivory and gilded parlor, the heavy afternoon heat weighing her down.

“There can be no other meaning, sister.” Fanning herself, her younger half-sister took another promenade around the parlor.

Dorritt ignored her mother’s shocked disapproval. She sensed that today was the climax of months of planning by her stepfather.

Dorritt’s tambour frame and stand sat in front of her at hand level. Placing tiny artful stitches helped her conceal how her heart skipped and jumped. How would it all play out today? Dorritt looked up at her half-sister, her opposite in everything, from Jewell’s olive skin and wavy blue-black hair to Dorritt’s fair skin and straight golden hair. “I believe love is necessary to marry well.”

Jewell made a sound of dismissal, her high-waisted white dress swayed with her wandering. “These odd humors, your peculiar comments all come from books. You read too much, Dorritt. Father always says so and mother agrees.”

“Then it must be so.” The heat of the afternoon was squeezing Dorritt like a sodden tourniquet. She put down her needle and pinched the bridge of her nose. Over the past months, she had stood back and read the signs of her stepfather’s devious manipulation of facts and circumstances. Of course, Jewell had no idea that the culmination of these might come today. But Dorritt knew well what red ink in a ledger meant.

With a handkerchief, her mother blotted her rosy, perspiring face, which still retained a faded beauty. “Please, Jewell, you must sit down and relax; compose yourself.”

“Why hasn’t André come yet?” Jewell attacked the lush Boston fern sitting on the stand by the French doors. She pulled off a frond and began stripping it. “He told me he would be asking my father’s permission today.”

There is many a slip between the cup and lip. “Perhaps he has been delayed.” Dorritt set another tiny stitch with rigid concentration.

Would her stepfather manage to work his trickery once more, bend reality to his selfish and greedy will? And more important, could Dorritt use it in her favor? Her hands stuttered and she had to pull the needle back out.

The sound of an approaching horse drew Jewell to the French doors that led to the garden. “I can’t see the rider. He has already dismounted under the porte cochere. That doesn’t look like André’s horse,” she added fretfully, and tossed the mangled frond back into the pot.

They all turned their heads to listen to the swishing of the grand front doors being parted, the murmur of their butler, the hum of another man’s voice, footsteps down the hallway to her stepfather’s den. If it wasn’t André, who could it be?

“It could be Philippe.” Jewell beamed and gave a little skip. “Maybe I will receive two offers of marriage today.”

One proposal would achieve your doting father’s goal, dear sister. Dorritt took a deep breath and began an intricate French knot.

“Do you think it might really be Philippe Marchand?” Their mother sounded awestruck. “Why he is worth nearly half a million.”

Jewell did a pirouette and swirled her hands in the air. “And I would be mistress of Marchand Plantation and eat blancmange every day.”

Dorritt imagined herself decorating her sister’s face with the white jellied dessert. She bent farther over her embroidery so neither her sister nor mother would see her unaccountable amusement. More of her odd humors.

“Come away from the window, Jewell,” her mother said in a low voice. “You must not appear as though you’re aware of any of this.”

For once, her younger half-sister obeyed. Jewell went and sat in the Chippendale chair beside Dorritt, lifting the needle from Dorritt’s hand and moving the tambour frame in front of herself.

Their mother uttered a soft scold for Jewell’s theft. But Jewell ignored it as usual.

Dorritt stopped to blot her face with her hankie. She could only hope that André had come to propose. If not André, then Philippe. If Jewell were married, this might ring the first bell of freedom for her.

“Don’t you dare take one stitch,” Dorritt ordered in an undertone, holding her own nervousness in strict check. “I embroider just as well as you do,” Jewell lied with a mocking smile. Her bitter chocolate eyes flashing, she boldly stuck the needle into the design.

Dorritt stood up. You need your face slapped, Jewell. But not by me. “I have work to do.” She strolled the length of the room, fanning herself with a woven palm fan. Glancing out the windows, she glimpsed the horse hitched in the shade of the porte cochere. She halted in midstep on her way to the hall. Surely it wasn’t he who had come and gone into her stepfather’s den. Surely not.

Just as she reached the door of the room, she heard footsteps coming toward the parlor. It was what she feared. The widower who was pursuing her, Job Wilkinson, strode beside her stepfather. Job looked like a white crane, and her stepfather waddled like a balding, plump self-satisfied gander. Not a good sign. The urge to flee nearly overcame her. But she composed herself, arranging her face into a sweet false smile. “Good day, Mr. Wilkinson. Won’t you come in and I will order tea to be served.” She turned in time to see her sister’s flushed, irritated face.

If only Dorritt could have enjoyed this experience of for once flouting her sister’s conceit. But I thought I made myself clear... How like a man to ignore her stated wishes.

“No tea,” her stepfather ordered. “Jewell and Mrs. Kilbride, come with me. We will leave these two young people alone.”

Pouting, Jewell threw down the needle and rose. Their mother

quickly led Jewell out. Her stepfather closed the pocket door to

the parlor, and they were alone.

Dorritt watched her abandoned needle sway, dangling on its silk thread tether. “Tell me that you didn’t...” She faced Mr. Wilkinson and read the truth. Her voice faded.

“Yes, I did seek your stepfather’s permission to pay my addresses to you. I thought it over many times since our last conversation.

Dorritt, you are just the wife I need. And just the mother I need for my little orphans. You are thrifty and good with children.”

Dorritt knew that she should be flattered by these words, but she wasn’t. You’ve just insulted me and you don’t even know it. “I told you, dear sir, that I don’t really wish for marriage.” Not a marriage of convenience. She knotted her hands together to keep from slapping his earnest face.

“Dorritt, I’m afraid that you may decide that you should change your mind.” He hesitated a moment. “I’ve heard some disturbing news about your stepfather’s . . .”

I’ve heard rumors too. And she knew more than the rumormongers did. “Talk is cheap and gossip is untrustworthy.” She turned away dismissively, trying to ignore the way her pulse suddenly galloped as if over rough turf.

“Belle Vista is about to be foreclosed.”

She stopped where she was. She wasn’t good at avoiding the truth. But she had been trying hard to avoid this particular truth, which had been bearing down on her for weeks. Cold liquid desolation trickled through her heart and then on through each vein.

“I am not unaware of my stepfather’s financial difficulties.”

Her murmured words were so inadequate to the situation.

The widower laid a gentle hand on her shoulder. “Dorritt, I know you’re not in love with me. And my sweet wife has only been gone for about nine months. But I’m certain there’s no one who will look askance if we married.”

She stiffened herself bit by bit against her sudden weakness.

“You know I don’t consider marriage as my purpose.”

“You don’t need to think of it. Just say yes. Dorritt, we are old friends. I’ll be a kind and indulgent husband.”

From outside, Dorritt heard another horse arrived. No doubt André was arriving to offer for Jewell --- she hoped. The fingers of despair slipping around her heart, Dorritt looked at her suitor. He was an honest man. But marry him? She couldn’t ignore how she felt... a sense of wrongness, that this wasn’t the path God had for her. “Thank you. But I just can’t.” Dorritt was aware of a new arrival at the door, now speaking to their butler.

“I feared that you would give me that reply. But I will merely say that my offer stands.” He stepped forward, lifted her hand to his lips and kissed it. “You need only send me a message.”

She accepted his homage with a curtsy and a soft “Merci.” He left her and clutched in a terrible lethargy; she returned to her chair and the tambour frame. The needle still hung by the thread, tethered just as she was to this place, these people. But she had barely lifted her needle to set a new stitch when the butler showed André, Jewell’s suitor, into the parlor.

André greeted her with a bow. She rose again, trying to look pleased. “I’m sure, sir, that you haven’t come to see me. Ah, I hear my sister’s footsteps.” Dorritt walked to the door and started to pass her sister. Jewell was entering the room, her face sparkled with welcome.

“Don’t leave us, Miss Dorritt,” André said, “I can only stay a moment. I’ve come to say farewell.”

“Farewell?” Jewell echoed him, shock vibrating in her tone. “Where are you going?”

“I only learned today that you will be leaving New Orleans. You will be sorely missed,” André said these words in a rush as if he’d rehearsed them over and over.

Dorritt almost pitied her sister. Of course, Jewell had not noticed anything, not picked up any troubling clues from her father’s behavior over the last critical month.

“Leaving New Orleans?” Jewell looked and sounded stunned.

“I’m sure I wish you well in Texas. And I have brought you a token to remember me by.” He pulled a small red velvet box from his coat pocket and handed it to Jewell. Smoothly he lifted her free hand to his lips. And then he disappeared. Taking a large income, acres of bottom land, and nearly one hundred slaves away with him. Ringing the death knell to more than Dorritt’s hope of emancipation.

Dorritt and her sister didn’t move. Then Jewell turned slowly and stared at Dorritt. “What has happened?” Jewell’s voice was low, harsh, and accusatory.

Dorritt had known how precarious their finances were ever since the bank Panic of 1819. But she was saved from answering by her stepfather hustling into the room.

“Why did André leave so suddenly?” Mr. Kilbride asked, for once looking surprised, troubled.

Jewell didn’t move; she merely held the velvet box in her open palm.

“That’s odd,” her mother said, entering the room at her husband’s elbow. “Surely he couldn’t have proposed and given you the ring in those few moments.”

Jewell still said nothing.

Dorritt actually pitied her. “André came to bid us farewell.” The words flowed from her lips as if she memorized them to recite, “We will be sorely missed but he wishes us well in Texas.”

Dorritt’s words brought Jewell out of her trance. “Texas!” she threw the word at her father. “Never!”

Her stepfather turned his glare to Dorritt. “He said Texas? How could he know?” He frowned and then said, “I feared that. His father must have overheard me when I was discussing the new settlement ...”Then he cursed softly.

Dorritt could only stare, feeling disconnected from them, from their emotions. Her own shock had broken her silence. She’d expected that news of their financial troubles would come to light. She even planned how to use it to escape her unhappy situation. But Texas? She found she could no longer keep up the charade of behaving as if she didn’t know how bad things were. “I knew we were close to ruin, but Texas? Why Texas?”

“You know how our finances stand,” he said, sounding angry at her. “I tried but couldn’t recoup our losses gaming over the last months, and instead of winning big, I lost money at the races. Everything went against me.” Mr. Kilbride took a menacing step toward her as if he were going to slap her.

Dorritt stared him down.

“We’re ruined?” Jewell blurted out. “We can’t be. We own this plantation and slaves and... This is insane.”

Mr. Kilbride took a hasty turn around the room. He halted in front of the fireplace. He pounded one hand into the other. “Since neither of you could do your duty to your parents and marry well, we’ll be leaving for Texas in ten days. I’ve done all I can to save our fortune, but the Panic of 1819 put us into deep debt. And there’s no way out. When a man needs a run of luck, it never comes.”

Dorritt knew that this was part of the truth. They had along with almost everyone else lost money in the Panic. But her stepfather’s penchant for gambling deep was what had ruined them. How could he have fooled himself into thinking that wagering would put them into the black? This accusation crawled up and pushed against her throat, clamoring to be voiced. She walked away and looked out through the white sheers.

“This is all your fault!” Mr. Kilbride declared.

The injustice of this made Dorritt whirl around. “I---”

But Mr. Kilbride shook his finger in Jewell’s face, not hers. “If you hadn’t kept André dancing on your string so long, he would have proposed a month or two ago. Texas is all your fault.” Jewell visibly shook with fury. She threw the velvet box at her father’s chest. It bounced off him, landing on the floor. “Why didn’t you tell me we were in danger?”

Their mother stooped, picked up the velvet box, and opened it. “André gave you a lovely silver locket.” This inconsequential comment was so out of tune with everyone else in the room that they all swung to look at her. “He didn’t have to come at all or give you a parting gift, dearest.” With a tremulous smile, their mother showed the locket nestled in the velvet.

Dorritt closed her eyes. Her mother strolled through life in a vague haze.

Jewell ignored their mother. “Father, we can’t leave New Orleans.”

“Stephen Austin has struck a bargain with the Spanish Crown to let Americans immigrate to the Texas territory. We will be given free land. And I have won a small herd of mustangs and longhorns we’ll pick up in Nacogdoches in a little over a month.

Then we head to the Brazos River.”

“I’m not going to Texas,” Jewell declared, her hands fisted.

“You don’t think I want to go, do you?” her father shot back. “Texas was my backup plan. I hoped you’d marry André and that the widower would take Dorritt off my hands. Then I’d take what was left from selling Belle Vista and with the generosity of my sons-in-law, your mother and I would have lived comfortably in the city.” Mr. Kilbride glared and then turned to Dorritt. “We leave in ten days. See to it.” He marched out the door.

Jewell stomped one of her feet. “I won’t. I won’t.”

Numb with shock, Dorritt watched her sister’s impotent rage. It was as if Jewell were expressing Dorritt’s anger as well as hers. Their mother went to Jewell and tried to comfort her. Jewell snatched the velvet box with the locket from her mother’s hand, dashed it to the floor, and stomped on it. Then she turned her fury onto Dorritt’s sampler, ripping it from the tambour frame and throwing it to the floor too. “André loved me. He did.”

“I’m sure he did.” Their mother patted Jewell’s shoulder. “Depend on it, his parents made him cry off. They are filled with their own consequence.”

And they knew that if André offered for you, Jewell, that he’d end up supporting your parents too. And I was to marry the widower. Dorritt knew her stepfather well enough to believe this. She wondered if any of this even crossed her mother’s mind. Dorritt had hoped her stepfather’s plan would work but would set her free too. If André had married Jewell and Belle Vista had been sold, Mr. Kilbride woudn’t need Dorritt to run the plantation that should have been his job. And Dorritt had hoped Mr. Wilkinson could be persuaded to bankroll the school for young ladies she’d hoped to open. And then she would have been set free.

But now what? Texas? Dorritt tried to think what to do in light of this. Their mother was holding a sobbing Jewell in her arms and stroking her back. “There, there. Someone will love you and marry you for yourself.”

Someone will love you and marry you for yourself. Dorritt went over to her chair, stooped and picked up her mishandled embroidery. She wondered if it even occurred to her mother to ask her if Wilkinson had indeed proposed to her. Of course not. Wilkinson proposing hadn’t meant as much to her stepfather because Wilkinson was not wealthy enough or foolish enough to support all the Kilbrides. He was only important if he would take Dorritt off Mr. Kilbride’s hands. Mother would never say to her, “Someone will love you and marry you for yourself.”

We leave in ten days. See to it. It had not been a request. There had been no discussion of how to take care of this overwhelming task. See to it. And he marched out. What would he do in ten days if nothing had been done? What if she just sat down and worked on her sampler for ten days? And did nothing?

Ignoring Dorritt completely, their mother led Jewell out the door, still supplying sympathy and comfort. Dorritt rose and stepped out the French doors. The garden was a riot of lush green, pink, and red. She looked up at the blue sky overhead, feeling herself shrinking from what lay ahead. “Oh, Father of the fatherless,” she murmured, “bless me.”

She’d been only a small girl in Virginia when her father had died. The pastor at the funeral had comforted her with the promise that God was the Father to the fatherless. Now she curled her hands around her embroidery as if clinging physically to Him. Her stomach rolled and clenched. Only one person would understand, comfort her. And Dorritt needed to tell her what had happened. She marched over the cobblestone path, around the house to the detached kitchen. She entered, and in a sudden passion, moved to toss her sampler into the low fire.

Her maid, Reva, who was helping the cook shuck corn, grabbed Dorritt’s wrist just in time and took the sampler. “What you doing? You been working on those azaleas for months.”

Dorritt faced her. “We’re leaving for Texas in ten days. I won’t have time for embroidery.” She ignored the loud shocked reaction that this announcement brought, and letting go of the cloth, Dorritt rushed back outside.

Still holding the embroidery, Reva hurried out behind her. “Miss Dorritt.”

Dorritt didn’t reply, just rushed farther along the cobblestone path, past the smokehouse and by the chicken yard to their private place. There she and Reva were shielded from the house by a windbreak of popple trees near the stream that flowed through a marsh into the Delta. A vast low marshland, it was the place they always went to talk where no one could overhear. Her only true friend, Reva had been with her since they were babies.

Sounding winded, Reva halted beside her. “Didn’t that André propose to Miss Jewell?”

“No.” Dorritt quivered from shock that was turning into anger.

“Why not? And what you talking about Texas for?”

Dorritt tried to calm herself. Reva was counting on her. “We’re ruined. André bid us a fond farewell. And we’re going to Texas where there is free land.”

Reva gawked at her. “Texas? I can’t believe it.”

“Believe it.” Dorritt’s throat was filling up, making it harder

to speak.

“What’re we going to do?” Reva asked, and gripped Dorritt’s elbow.

Dorritt blinked her eyes to hold in tears. “I’ll think of something.”

“The widower came today too,” Reva probed politely.

Dorritt gave a sharp, mirthless laugh. “He proposed because I’m thrifty and would make a good mother for his little orphans. He promised to be a kind and indulgent husband.”

“Oh.” Reva sounded uncertain.

Dorritt finally looked into Reva’s pretty face, the color of coffee with cream and with large nearly black eyes. “You think I should have accepted him?”

“Well, we would get away from your stepdaddy and we wouldn’t be going to Texas.”

Resentment swelling inside her, Dorritt folded her arms. “I’d hoped Mr. Wilkinson would back me financially to start our finishing school. I’ve told him that repeatedly, but it wasn’t what he wanted to hear so he ignored me.” Just like men do. They only hear what they want to and a woman is easy to disregard. “It would have freed both of us. I would have shamed Mr. Kilbride into giving you to me as a gift. And if André had married Jewell, my stepfather would have. Then we’d have been free. Or as free as two unmarried women in New Orleans can be.”

Reva patted her shoulder. “Could you be happy with Mr. Wilkinson? He not a bad man.”

Dorritt looked down, her chin quivered with the insult he’d given her. “I won’t be a convenience to any man. I can’t, won’t, marry unless I trust a man and love him. And that will never happen.” She looked to Reva. “I can leave a stepfather, but I can’t leave a husband.”

Dorritt admitted that she truly longed to be loved by a man, just like Jewell. If only the widower had said anything about his feelings for her. But no. He’d had some respect for her talents, that was all. Will there ever be a love like that in any man’s heart for me? “No,” she whispered, “I will never marry.”

With her usual practicality, Reva asked, “But how’re we going to leave your stepdaddy in Texas?”

“I’ll think of a way.” Dorritt began to gather her scattered wits, pulling herself together. “I am a well-educated lady of good family. That is respected anywhere. We’ll stay together, Reva. I promise you.”

Reva looked down. “If Mr. Kilbride is ruined, he might sell me.”

Dorritt constricted inside, so tight, so painful. “If it comes to that,” she forced out the words, “your going on the block, I’ll accept Mr. Wilkinson’s offer and ask him to buy you as my maid.”

Dorritt took Reva’s hand. “We won’t be parted. I promise.”

Reva squeezed Dorritt’s hand. “I hear there no slavery in Texas.”

“Yes, I know.” Dorritt tried to take a deep breath, but couldn’t yet.

“Maybe I go to Texas and find freedom. We find freedom.”

Dorritt pulled Reva’s hand closer and gazed out over the vast green marshland in front of them. Could they be free in Texas? She stared at the summer sky, still pure blue and cloudless. Sometimes it seemed as though God waited just behind the sky, the blue curtain. She murmured her favorite verses from Psalm 37, the ones that gave her and Reva strength in hard times.

Trust in the Lord, and do good; so thou shall dwell in the land…

Delight thyself also in the Lord; and he shall give you the desires of thine heart.

***

Dorritt blinked back tears. Father, no one but Reva knows me or sees me or loves me but You.

Leaving New Orleans for Texas terrified her. Suddenly, she felt so much apprehension and excitement it was as if she were standing on the edge of a cliff about to step off. She whispered, “Maybe we can be free in Texas.”

Her whisper was swallowed up by the squawk of a snowy egret. It lifted off its spindly legs and flew low over the water first and then higher, higher. And then she saw it. If the ungainly egret could fly... maybe they could be free in Texas. Somehow... some way.

Dorritt took a deep breath and stepped off the cliff.

Excerpted from THE DESIRES OF HER HEART: Texas: Star of Destiny, Book 1 © Copyright 2011 by Lyn Cote. Reprinted with permission by Avon Inspire. All rights reserved.

The Desires of Her Heart: Texas Star of Destiny, Book 1

- Genres: Christian, Historical Romance

- paperback: 306 pages

- Publisher: Avon Inspire

- ISBN-10: 0061373419

- ISBN-13: 9780061373411