Excerpt

Excerpt

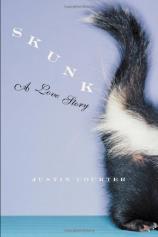

Skunk: A Love Story

Chapter 1

Only three years ago did I finally decide to get a skunk of my own. This was after a long, tentative courtship of the skunk scent. If I were driving on a country road and smelled skunk, I immediately pulled over and sat, sometimes for hours, with all the windows rolled down, breathing deeply and letting my thoughts drift among whatever daydreams

the scent inspired. I often packed a lunch and devoted my Sunday to one of these drives. But I longed for the pleasure of enjoying the scent of the skunk entirely at my leisure.

By the time I was thirty years old, the notion that I was completely self-sufficient and could do, more or less, what I pleased, began to take shape somewhere in my mind. I had a job as a copywriter for Grund & Greene, a publisher of law books, and I had my own small house in New Essex, a relatively tranquil suburb. I was proud of my house—sad, gray shoe box that it was—with its knee-high hedge, which I kept squarely trimmed, running across the front like a fender. Having scrimped and saved, having lived in tiny, roach-ridden apartments for years, I was at last the owner of something more substantial than the old, smoke-colored Eldorado in which I got around on weekends.

As I am one who has learned to prepare for all of life’s inevitabilities, I built a six-foot fence along the perimeter of my tiny back yard and constructed a hutch about the size of a dog house. Thereafter, several weekends were devoted to tramping around some woods outside town until the day I came across Homer.

It was a crisp autumn afternoon. The sky was a gray sheet of legal bond resume paper upon which were scribbled the leafless branches of maples and birches, and I strode through woods carrying a large burlap sack. When I first spotted Homer, he was rooting around in a pile of dead leaves. Though I tried to approach him stealthily, my feet crunched leaves and snapped twigs. The skunk stopped what he was doing, turned to face me, and sprung suddenly to attention like a puppet on a string. I froze. He arched his back and seemed to grow taller. I took a slow step forward. The little beast hissed, I took a second step, and he began to thump the ground with his forepaws. He became increasingly agitated, gradually raising his plume of a tail until it stood straight up. Then, when I was still about six feet from him, he spun around, quicker than a gunslinger, and sprayed in my direction. He wasn’t a bad shot. The yellow juice he emitted splattered my trousers, and any other predator he could have considered thwarted. Poor fellow. He couldn’t possibly have known that what he was doing was tantamount to slipping an aphrodisiac to a nymphomaniac.

The scent of skunk musk is the richest of all olfactory pleasures. It is a bitter sweet combination of lilac, tilled earth, McDougal’s beer, dogwood blossoms, apple pie, fresh snow and Moschus—the miniature Himalayan musk deer. And the effect on the mind is astonishing. Skunk musk brings the innocence of childhood, the lasciviousness of adolescence and the wisdom of old age to the surface of one’s consciousness all at once. I sucked Homer’s perfume deep into my lungs. My vision blurred, eyes teared, the burlap sack fell from my hands and I became slightly dizzy. Homer began to mosey off through the forest. I returned to my senses and snatched the bag up from the ground. I simply had to have him. I chased him as he scurried about—under bushes, through piles of leaves and was able to get the sack over him just as he was about to scoot down a hole at the base of a tree. He writhed around and sprayed more of his delicious scent as I tied a knot at the top of the sack and carried him out of the woods. I placed him beside me on the seat of the car and he continued to wriggle for the first quarter hour of the ride home, at which point he got tired and lay still. I opened the sack in front of the hutch I’d built in the back yard and he moseyed right into his new apartment as if he’d never lived anywhere else. It was then that I decided upon his name. “Welcome home, Homer,” I said. But he ignored the hutch after the first night and dug a hole beneath it the next, so that he only used the floor of the structure I’d built as a roof for his subterranean abode.

There was very nearly what one might call a spring in my step on Monday morning when I left the house to walk to the commuter train. Spending the weekend with Homer had given my life an exciting new dimension. I actually waved at Mrs. Endicott, the annoying old widow who lived next door and who owned a high-strung Chihuahua called Tesa. Mrs. Endicott was retrieving the newspaper from her front yard and Tesa stood at her side yapping at me like a battery-operated toy. Mrs. Endicott liked to talk to me practically whenever I stepped outside, providing me with updates on her children, her grandchildren, her rheumatism and other dull topics. She also badgered me with questions. She asked me who my girlfriend was, when I intended to get married, and so forth.

“Hey, Damien,” she said that morning, waving me over to her. I was embarrassed for her because she was standing there in the middle of her yard in a flower-print housecoat, with pink curlers decorating her head. I walked over to her. “What’s going on in your yard, there?” she asked. Her face was wrinkled like a used paper bag, and her sagging cheeks quivered when she spoke. Tesa continued her yapping throughout our conversation. “Nothing’s ‘going on,’ Mrs. Endicott,” I said. Of the long list of unpleasant

qualities this woman exhibited, her prying nature was the most abhorrent.

“You’ve got a dog now don’t you, a little puppy? That’s good, companionship

is good. I’m always saying to Noah, my nephew, you oughta get a nice dog, I says, you need a friend. Living all alone like that makes you crazy. Butyou,” here Mrs. Endicott jabbed me in the chest with a bony finger and smiled, “you got a good head on your shoulders. I always said you did. Now all you need is a good woman to take care of you.”

I began turning away. I detest being poked and prodded physically or psychologically. Crazy indeed. Mrs. Endicott had told me that she herself had lived alone for the past ten years. “Thank you Mrs. Endicott. I think I’ll be on my way.”

She grabbed my arm and held me there. “The only thing is, Damien, you gotta clean up after a dog. I can smell it over in my yard. Wait.” She pulled me a little closer and sniffed deeply. This caused a most disagreeable racket—snot burbled in her nose and phlegm rattled in her throat. I doubted she’d be able to smell the smoke if she were sitting on a burning sofa. “I’m a little stuffed up,” she said, “but I can even smell it on you now. It’s not good. You take him on walks or train him to go in the far corner of the yard, you hear?” She smiled, peering with her cataract-clouded eyes into my bespectacled ones for

a moment, then released my arm. “Run along now, you’ll be late for work,” she said.

As I turned and began to walk away, I noticed that Tesa had stopped yapping. Then I felt her attack from behind. Her tiny teeth slipping from around my ankle, she contented herself by yanking at my pant leg and growling fiercely, as if truly committed to removing my pants. I shook my leg vigorously and was about to give her a good swift kick with my other foot, when Mrs. Endicott called, “That’s enough now Tesa.” Tesa released my pants and stood barking until I’d reached the end of the street. Luckily, she’d put only a few pin holes in my pants. I always wore polyester suits, which I found practical, affordable and quite durable; I owned one blue, one gray and one brown. What did trouble me a bit was that Tesa had put a two-inchlong scratch in the leather of my sturdy brown shoes, the same type I’d worn since I was a boy, and on which I always maintained a flawless, military shine.

When I got on the commuter train people parted for me like the Red Sea before Moses. A woman with watery eyes, who appeared to have a sinus irritation, vacated a seat next to where I stood and moved to the front, holding a tissue over her nose. I happily took the seat and opened my paperback copy of Alma Chesnut Moore’s How to Clean Everything, which is among my favorite works of nonfiction.

I got to the office at ten minutes before nine, as always, and began working immediately. Frank Farnsworth, whose cubicle was adjacent to mine, got in at nine twenty-three, huffing and puffing, and threw his briefcase against the wall of his cubicle that bordered mine. This disrupted my concentration on the wording of a brochure for what may very well have been the definitive text on real estate litigation. I had to submit a draft of this piece to John Hastings, my supervisor, later that morning. I’d already written and revised it several times, but I always double- and triple-checked things before submitting them to Hastings. Farnsworth made a great deal of noise shuffling papers about in his cubicle and muttering to himself. I heard him pick up his phone. Here we go again, I thought.

“Hey honey,” he said loudly, “did you get Suzie to school on time?” He paused for a moment. “I know, I know, I think it’s because she’s still getting over that cold… No, look, now I can’t be responsible for everything all the time, okay? I’m running my ass ragged trying to keep on top of things here, and I can’t be expected to put everything on hold if I notice the kid’s started to sniffle or—what?… Yeah I know about the goddamn wedding, I don’t think your sister will let me forget about it for five minutes. Jesus, something stinks in here… Because I didn’t have time, not because I forgot. Macy’s isn’t on my way, and the last time I was late you went ballistic. Man, I think I stepped in something on the way to work… No, listen, I called you just now because I wanted to straighten out something else and now… Okay, fine. Yeah. Okay. Alright, I’ll talk to you then.” Farnsworth dropped the receiver noisily, got up and left his cubicle. I could hear the clanging of metal and glass from all the way at the other end of the hall as Farnsworth molested the coffee maker. He came back to his cubicle and banged his mug down on his desk.

“Shit,” he said, “God damn it.” Then he was standing there in my cubicle. “Hey Damien, can I bother you for a second?” It had already been much longer than that, so I could see no reason he needed permission to continue the practice. Without moving my chair, I rotated my head to face him. Farnsworth’s necktie was loosened, the top button of his shirt unfastened, his sleeves rolled up, and his hair disheveled. His demeanor suggested that rather than having just shown up at the office, he had already worked an entire day and was preparing to unwind.

“I just spilled coffee all over my stupid keyboard,” he said. “Is that going to ruin it completely? Do you know?” Farnsworth’s face began to look as if he’d taken a bite of a rancid piece of cheese. He began sneezing, and sneezed five times in my cubicle without once covering his mouth, though he did turn his face away from me. When he’d finished he said, “God, do you smell that? I think it’s even stronger in here. Jeez, it’s terrible.”

Though my posture is always nearly perfect, I felt myself sit up straighter upon hearing these words. “To what smell do you refer?” I asked.

He stepped toward me and sniffed. He stepped back again and gave me a puzzled look. “Well, anyway, do you know what I should do about my keyboard?” he asked. “I mean, is it okay to just wipe it off with a damp rag or what?”

“I would do nothing without first consulting Mr. Daltry regarding the matter,” I replied. Sean Daltry was the building’s maintenance man.

Farnsworth rolled his eyes. “Yeah, I guess, I was just wondering if you might know.”

“Well I don’t suppose I do,” I said. In fact, Alma Moore’s book had been written before the advent of the personal computer. “And I don’t suppose I really have all morning to sit here chatting with you about your keyboard, Mr. Farnsworth.”

Farnsworth raised his hands, palms facing outward. “Whoah, take it easy, bud. Forget I was here, okay?” He backed out of my cubicle. I turned back to the screen of my computer. “What the hell’s the matter with everybody today?” I heard Farnsworth say behind me to someone passing in the hall.

That night when I went home, I put a small portion of my dinner in a dish outside Homer’s burrow. I did not try to get him to spray at me. In those first few weeks after Homer’s arrival, I only allowed myself a bit of skunk musk on the weekends, and then only after I’d completed all my chores, which included going to the dump, doing the food shopping for the week and cleaning the house from top to bottom. I was always extremely meticulous in this exercise—going down on my hands and knees with a toothbrush to get the mildew that grew between the tiles in the corners of the shower, polishing the pipes beneath the kitchen sink, and so on. Then I took a shower, shaved, stretching the skin to get a close swipe at the stubble in the dip beneath my chin, and combed my hair, which is jet black and a bit too wavy. If I let it go for very long it gives me a wild appearance, which I find unbecoming. For this reason I visited the barber once a month, which I thoroughly enjoyed, because I find it satisfying to cut off loose ends. My appearance, I believed, was one of economy, efficiency. I am neither excessively tall nor excessively short. I carry no surplus flesh. My nose, the sense organ I prize the most, is straight and ends in a fairly sharp point. My eyes are as dark as my hair and are extremely weak. For this reason I have worn thick glasses since I can remember. When I worked at Grund & Greene, I still had the same pair of black frames that had served me since high school, though my prescription had changed many times. Despite the fact that I am quite capable of making my way in the modern world, I know what a miserably inadequate creature, despite my efforts, I truly am. My constitution is so delicate and my eyes so weak that I would not have survived if I had dwelt in an earlier era of history, say, in the Stone Age. I would have been one of the casualties of natural selection—either killed by a wild boar during a hunt because I could not see it coming, or maimed by one of the bigger, stronger boys of the tribe before I reached the age where humans begin copulating—and thus would have been unlikely to pass my defective genes on to future generations. Hence, the race would have continued to grow stronger, as indeed it should. I consider it an abomination that I have actually participated in procreation. I never intended to.

Anyway, only after all the previously described observations of hygiene and domestic maintenance were completed would I go out in the yard to chase Homer. I trapped him against the fence and gave him as much of a scare as I could, and in turn he showered me with that sublime scent of his. My head was sent spinning with the strength of his emissions the first few times—my sight blurring and sense of balance temporarily upset—but I began to develop a tolerance to him and by the fifth weekend I was doing my best to get him to spray at me two or three times in an afternoon. I found that the smell made me hungry and I often went out in the yard to eat my dinner in an appetizing cloud of skunk scent. After doing this a few weekends, I thought to myself, now wouldn’t it be even more sensuous if I could actually taste the skunk musk, actually ingest it?

I was not about to butcher poor Homer and eat the little chap, heavens no. I was becoming quite attached to the furry fellow. He had a pleasant enough disposition and kept to himself, which was more than could be said for most people. So I began to look forward, not just to his scent, but to the sight of him when I came home from work at the end of the day. And besides, if I ate him, I’d immediately be back where I’d started, without my own source of skunk musk.

In a single blast, Homer usually emitted about half a fluid ounce of the sticky, oily, yellow substance known as musk. Getting even a small amount of this fluid into my food took some doing. For two or three weekends, when I got Homer out of his burrow and chased him about the yard, I held a hot plate of spaghetti or a vegetable and tofu stir-fry out in front of me, so that when he finally stopped to spray at me, he got at least a few drops of the fluid on the plate. After a time, even the most exquisite dish seemed incomplete without having been seasoned with fresh skunk musk.

One day, about a month and a half after Homer had joined me, I discovered the conspiracy at the office. I left my cubicle at eleven forty-five to get a drink of water. In my peripheral vision, I noticed Farnsworth glancing up at me from his desk as I passed his cubicle. He’d been giving me insinuating looks for some time now, and on returning to my cubicle, I went around the other way, simply to avoid his eyes. He must have assumed I’d gone to lunch, because after I sat down at my desk, before I could put my fingers to my keyboard, I heard my name.

“You really think it’s Damien?” the voice said. It was John Schrempp, an annoying little fat person. Whatever he did for our department, it must have involved the consumption of vast quantities of Twinkies, Ho Hos and chocolate Ding Dongs, because I never saw the man do anything else. Once, he came into my cubicle to ask a question about one of my back ads, munching on something chocolate and cream-filled. He spoke while masticating, giving me a full view of the wet, brown mush in his mouth, then licked each of his fingers with a moist smacking sound and placed the copy on my desk with dark brown smears across it.

“I know it’s Damien,” Farnsworth said. “Didn’t you notice how much stronger the smell is right around here?”

I felt the clenching of nervous fear in my stomach. I heard the clomp of Barbara Flemming’s high heels coming down the hall.

“Hey Barbara,” Farnsworth said, “have you noticed the stench around here?” I didn’t think there was much possibililty that Flemming could have noticed any scent other than her own. She wore enough perfume to make her presence known from a distance of several yards.

“Yes, I have noticed it. I spoke with Sean about it. He thinks a skunk got into one of the walls and died. He’s going to try to find it and get rid of it this week,” she said.

“Well he can crawl around every crawl space and rip apart all the walls in the damn building, but Damien will still be sitting right out here in his cubicle,” Farnsworth said. Schrempp chuckled. “I’m not kidding,” Farnsworth said, emphatically. “I was in his cubicle the other day. The guy smells like a freaking skunk.”

I was simultaneously enraged and mortified. I felt like I was in boarding school again. Imagine, people talking behind my back! How very sloppy and juvenile. It was that cootie business all over again. I wanted to say something out loud in my defense, but at the same time I wanted to curl up under my desk and cover my ears with my hands.

“Well, the smell is a lot stronger over here in this part of the office, I’ll give you that,” Schrempp said.

“You know, I wouldn’t doubt that it is Damien,” Flemming said.

“There’s something creepy about that guy. He’s so skinny and dark, and he acts like some kind of robotic rodent.” While they spoke, I quietly got up from my chair and went and crouched in the corner of my cubicle. From this position I could still hear what they said, but when the others left Farnsworth’s cubicle, they wouldn’t be able to see me. I remained there for the next twenty minutes.

Of course the inevitable occurred. Homer got used to me. After about three months he could no longer be frightened. When he saw me emerge from the house, he toddled over and rubbed himself against my leg and licked my hand. After all, I fed and housed him, what could I expect? So we became friends. I sat on the porch, rubbed his belly and read to him from theCollected Works of E.B. White. He seemed to like Charlotte’s Web in particular, but also showed great appreciation for Stuart Little. He was a much better friend than any I’d ever had. But then, I hadn’t had any to speak of since the day I was separated from my mother. I generally don’t care for people. At best, they talk constantly about themselves, dig wax from their ears with their pinkie fingers and indulge in other repulsive habits. At worst, they get themselves involved in such hopeless entanglements as marriage, misuse one another, betray, rape and kill each other. I found Homer’s nature much more agreeable.

But alas, though I had gained a friend, I now seldom got to enjoy such a rich emission from Homer as I had in the beginning of our relationship, and found myself lying awake at night wishing for the single strong whiff that would send me into olfactory ecstasy. I was able to frighten him enough now and then to get him to spray, but my methods for doing so became increasingly contrived. And I felt guilty sneaking up on him, or dressing up in costume to frighten him.

Then, one Sunday afternoon, I made my discovery. Homer and I were playfully wrestling about, as we had gotten in the habit of doing. I would lie on my back on the ground and let him walk over the length of my body until he got to my head, at which point I would grab him with both hands, pin him to the ground and tickle his belly. During one of these tickling sessions I squeezed him and he suddenly sprayed. It was one of the greatest blasts of his scent I could have asked for. When I’d recovered from this surprise gift, I tried to figure out what had caused it. I wondered if the squeezing had frightened him in some way, but he seemed quite calm, if slightly bewildered. I squeezed him again, but nothing happened. After a little experimenting, I found that if I placed both thumbs just beneath the rib cage and applied just the right amount of pressure, with a quick, down and-up massaging motion, it invariably caused Homer to spray. If I pressed too hard, it didn’t work—he merely stuck out his tiny tongue and made a gagging sound. Nor did it work if the pressure was too light. With a little practice, though, I found I could control the intensity and the length of the emission that was produced.

“Eureka!” I shouted, jumping to my feet. Homer looked up at me placidly. “Homer, do you know what this means?” I said. “Absolute bliss! No more chasing you around the yard with a Halloween mask and a plate of pork chops. No. I can simply pick you up whenever I want and squeeze a bit of that delightful seasoning onto my plate—a dash on my salad, a liberal squirt into the entrée and perhaps a drop in my tea afterwards. Oh, it is too good to be true!” Homer himself looked pleased. He seemed to get some satisfaction out of being relieved of his musk, just as cows are known to enjoy being milked.

I let Homer move into the house and he soon became an indispensable part of the place. It was comforting to have his warm body nestled beside me on the couch while I read at night. And I got accustomed to his habit of licking the water from my ankles after I stepped out of the shower. I cut a hole in the bottom of the back door and installed a little plastic flap so he could go in and out as he pleased. And any time I felt like it, I picked him up and squeezed him for a little of his scent. I soon gave up the rule I’d made for myself about only using him on weekends. The first thing I did when I got home from work was pick Homer up from where he greeted me at the front door and give him a little squeeze.

What my discovery of the abdominal manipulation of the musk gland had done was give me the liberty to drink musk whenever I chose. And this is quite different from smelling it from a few yards away, or even from using a few drops of the fluid to season one’s casserole. Taken with food, the musk’s potency is significantly reduced. Direct ingestion introduces one to a completely different aspect of the juice.

The first time I took skunk musk straight, the effects were overwhelming. I held Homer over my head, squeezed a full shot straight down my throat, and was aware of a burning sensation in my sinuses for an instant before I blacked out. I awoke on the ground, with little idea of how much time had passed. By overdosing the first few times I drank musk, I missed out on much of the experience. Measuring my dosage, I found I could administer myself just enough to induce a sense of euphoria without passing out. Instead of squeezing a full shot directly down my throat, I squeezed Homer over a glass and then used an eyedropper to obtain a single droplet I let fall to my tongue. This I immediately chased down with a glass of water.

Most people are unaware of the fact that the skunk gland is the key to an entirely different realm of sensation. I would say the world of a musk dream is the everyday world seen with better clarity, but this is often said about the effect of such inferior chemicals as THC. When embarking upon a musk dream, one graduates to a higher plane of existence than the one people normally inhabit. I would go so far as to say that a person who has not experienced a skunk musk dream is like one who has seen only two dimensions of a three-dimensional world. For such a person, I will make a comparison (though this is probably akin to describing colors by comparing them to textures for a blind man) based on what I’ve read about the effects of other drugs. Skunk musk has the anesthetizing effects of an opiate and produces the sense of heightened awareness of a hallucinogen, without the disagreeable side effects of constipation, hallucination and paranoia. But what makes the musk dream even more complex than anything possible with botanically-derived drugs is the exhilaration. Research I later undertook revealed that this is the result of the large quantity of animal endorphins contained in skunk musk. The immediate effect of ingestion of the appropriate dosage of musk is at once subtle and dramatic. All the tedious pressures and concerns of daily life drop away like a suit of clothes so cheap that it actually dissolves in the sudden storm of chemicals, and one finds oneself instead wrapped in a robe of serenity. The musk dreamer’s dream is one that emerges from his own subconscious and over which he has complete control.

But of course euphoria is always followed by depression. And as my tolerance for skunk musk increased, so did my need for the sensation that had not been a need before I knew the sensation existed. Developed over a period of time, a tolerance of a beloved substance, and a tailoring of one’s lifestyle to the enjoyment of that substance, can enrich one’s life. It is one of the tragedies of modern civilization that the tendency to cultivate such a lifestyle is, in ignorance, condemned as an “addiction” by society’s sentinels, people who are fundamentally intolerant. They are the same petty, insecure busybodies who took my mother away and whom I shall never forgive or trust ever again.

Excerpted from Skunk © Copyright 2012 by Justin Courter. Reprinted with permission by Omnidawn Publishing. All rights reserved.

Skunk: A Love Story

- paperback: 352 pages

- Publisher: Omnidawn Publishing

- ISBN-10: 189065020X

- ISBN-13: 9781890650209