Excerpt

Excerpt

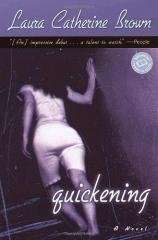

Quickening

The morning I was leaving for college, Mom fainted. She had been playing solitaire at the kitchen table and had stood up too fast.

I was washing the car with Dad, who'd gone inside for matches, then came back out and said, "She's down."

I dropped the hose. Water pooled in the crevices where weeds grew, ran down the driveway and out into the street. "Did you call Dr. Wykoff?" I followed Dad into the kitchen.

"Now, how'm I going to do that, Mandy?"

Of course. The phone had been cut off. We hadn't paid the bill.

The cards were scattered over the table. Mom lay on the kitchen floor, her pilly pink robe half buttoned and wrinkled around her fleshy splayed legs, slippers still on her feet. Her blue eyes bulged and blinked. "It took you long enough," she said as we bent over to help. She twisted my forearms in a vise grip while Dad, wheezing, cigarette hanging from between his clenched lips, hoisted her up from behind. "Be careful, for God's sake," she said. "You know how easily I bruise."

"Can you make it to the car?" he asked. "We'll drive you to Ransomville General."

"I'm not going to the hospital looking like this! It's just a meegrain. The dizziness will pass. Help me to bed."

"They're called migraines, Mom." I took one side and Dad took the other.

"Would you listen to smarty-pants!" Mom was short but wide, and solid, still a dead weight after her faint. Her robe smelled of trapped sweat.

"Are you sure you don't want to go to the hospital?" I asked.

"Didn't I just say no? Don't treat me like I'm stupid, Miranda. I had the brains for college, too, you know . . ."

I should have guessed it was about college.

The three of us stumbled through the kitchen door, down the little hall, into the bedroom. The bed springs squeaked and squealed as Mom settled in. "Oh dear," she muttered. "I won't be able to drive with you to your college."

"Gee, what a surprise. But I'm still going." All through high school, I had worked toward college. I had been in the honor society, had gotten a partial scholarship, a federal grant, a student loan, and a work-study grant. This moment of leaving had been the point whenever I thought, What's the point?

"And you can't stop me." I walked out as Dad was turning on the electric space heater and the humidifier, pulling the curtains shut. "Did I say anything? What's the matter with her!" Mom shouted.

"Bring me my pills, Miranda Jane!"

She hadn't left the county in years. It was predictable. Why did it upset me? I didn't even want her to go. My heart banged out of control against my rib cage, in panic and hope that Mom would just disappear, even if it meant her dying. I took the flat plastic box out of the refrigerator and brought it to her. It was separated into compartments designating times of the day and days of the week, the measure of Mom's life.

For her migraines, she took Fiorinal or Naprosyn, depending on the nature of her pain. For the lupus, she took Prednisone twice a day. For her postpartum depression, she had been on Elavil for eighteen years. Halcion to fall asleep. Dexamethasone for her asthma. Premarin since the hysterectomy. And Xanax for the panic attacks. When I was little, we did drills where she pretended some health crisis and I rushed to the refrigerator to give her a pill. "No!" she would scream. "I'm a dead woman. You've just given me the wrong medication!"

I had since resolved never to take pills, not even aspirin.

"Do me a favor. Tell your father to shave before he goes. He looks like a bum." Her round face was as pale as her worn pillowcase. I handed her a Naprosyn and a small glass of water.

"Be a daughter to me, please." She pointed to the chair by her bedside table. The humidifier blew steam on the wallpaper, which bubbled and buckled in the damp corner. The room stank of camphor, menthol, and bad breath. I wanted a cigarette. How had Dad slipped out of the room so quick? "I have to finish washing the car," I said. "Your father said he would finish."

"No, really, I . . ." I edged toward the door.

"Frank!" Mom bellowed. "Tell Miranda you'll finish the car."

I heard the back door slam.

"He said he would finish," she insisted.

I sat down. Her bedside table smelled charred and musty. She had bought it years ago at a fire sale. Cluttered on its surface were a bell, a box of tissues, an ashtray, a thermometer, Vaseline, and a battery-powered blood pressure machine. The place of honor was held by a framed picture of Mom's mother, sitting on the porch, squinting and mean. Dad had taken it. Every night before she went to sleep, Mom kissed this picture. Or so she claimed.

"You're all packed," she said. "You've got your clothes."

How long was she going to keep me here? "Yes. I've got my clothes."

We had gone over them last week, and all the dresses Mom had sewn for herself years ago were mine now, for college. All the little replicas of those dresses, also sewn by her but worn by me until I was twelve or so, were packed in cardboard boxes and piled in the basement. In my bag was the floral-patterned skirt with the ruffle at the bottom and buttons running all the way up. I managed to button it only by holding my breath. It had a blouse with bell sleeves that matched. There was a green dress with a princess collar that choked and a too-tight skirt with a houndstooth-check pattern.

Mom and I just weren't shaped the same. I was taller, rounder, bigger. Mom called me chunky. She had said, "We can let out the waist in that one."

But she hadn't sewn in ages, and I didn't want to be the reason for her starting again. I wasn't going to wear her dresses anyway. I had jeans, T-shirts, normal things. "It's okay, Mom. I like it this way." I had minced after her in a skirt so tight that I couldn't take a normal step.

"I'm sure that sewing machine is somewhere around here." She had opened closets, peeked along shelves, pulled open dresser drawers, wandered out to the kitchen, a wake of hanging doors behind her. But she didn't think of the basement, and I was careful not to suggest it.

"Yes," I repeated. "I've got my clothes." I folded my hands in my lap. My fingertips were raw, chapped, my nails bitten to the quick. Big hands. Ugly hands.

"I remember you as a little girl, picking daisies out in the backyard in your sunsuit. You made a daisy chain for me. You were such a precious thing. Now you're going to college!" Mom inhaled sharply, exhaling a sob.

"Don't cry, Mom. Please." Her sobs always forced me open. I fought it. No. I didn't remember any daisy chains. No, I wasn't going to cry. But the tears welled up and I bent my head to wipe them away, imagining a child in a sundress picking daisies for a healthy, vibrant mother who laughed a musical laugh. It was only a fantasy.

I was surprised she had declined Dad's offer to drive her to the hospital, her second home. She seemed happier in a hospital bed, attached to intravenous devices, her face flushed and cheerful against a clean white pillow. "I got 'em stumped," she would say.

She had actually been written up in a textbook called Autoimmune Disease: Symptoms and Pathology. Her case appeared in a section on the difficulty of diagnoses and the flare-up remission pattern of symptoms. Her name wasn't mentioned. She was the thirty-seven-year- old female patient of Bernard Wykoff, M.D. It was back in 1975, ten years ago, and she still kept the book under her bed. "You can bring me my jewelry box," she said.

I got up, sniffing down my tears, and walked around the bed to the dresser. There were weeping willows trailing sun-dappled leaves by a brook on the ceramic lid of Mom's jewelry box. She thought she was giving me a treat by going through her jewelry, but I was too old. I felt another sob coming. "I don't have time for this, Mom."

"Just open it. Pull out the top bit. Ow! This pain is like trolls throwing stones in my head. I should be used to it, God knows. The only meegrain-free period in my life was when I was pregnant with you." She was stroking her stomach, rustling the housedress she wore beneath her robe.

I pulled out the top container of the jewelry box, where she kept her earrings, and squashed inside was a roll of bills.

"That's for you," Mom said from her bed. "For college. For the niceties."

The bills were greasy, soft from handling.

"I've been saving it, and you're going to need some cash. And . . ." She shut her eyes. "Don't tell your father."

The scent of calamine lotion wafted from her skin as I leaned in to kiss her forehead, but she tilted her face back, her mouth pink with the Pepto-Bismol she took to counteract the nausea from the painkillers, and our lips mashed moistly, hers soft and open and mine clenched shut.

Excerpted from Quickening © Copyright 2012 by Laura Catherine Brown. Reprinted with permission by Ballantine. All rights reserved.

Quickening

- paperback: 352 pages

- Publisher: Ballantine Books

- ISBN-10: 034543773X

- ISBN-13: 9780345437730