Excerpt

Excerpt

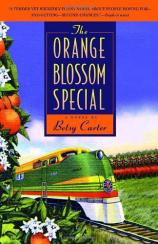

Orange Blossom Special

ONE

The morning after the letter arrived, Tessie Lockhart dressed with care in a navy blue skirt, red cinch belt, and blue-and-white-striped cotton blouse. Instead of letting her hair lie limp around her shoulders, as she had since Jerry died, she pinned it up in a French twist. And for the first time in God knows how long, she stood in front of the mirror and put on the bright red lipstick that had sat unused in her drawer for nearly three years. She penciled on some eyeliner and even dabbed on Jean Naté.

Jerry died two and a half years earlier and Tessie hadn't given her appearance a second thought since. When he was alive, he would stroke her hair and tell her that she looked pretty, like the actress Joanne Woodward. He even nicknamed her Jo. She'd never fallen under a man's gaze quite that way, and though she'd studied pictures of Joanne Woodward in the movie magazines and even started wearing her hair in a pony tail the way Joanne Woodward did, Tessie never really saw the resemblance. Not that it mattered. Just the look in Jerry's eyes when he would say, "God, Jo, you are so beautiful," that and the way he'd pull her toward him was all the impetus she needed to turn up the collars of her shirtwaist dresses, and wear her bangs short just like Joanne Woodward had worn hers in a movie magazine photo spread.

She told her boss that she had to go see Dinah's teacher at school and would be away for a couple of hours. Instead, she got on the bus and went to Morris Library at Southern Illinois University. She'd gone by it hundreds of times in the past thirty-six years, but had never set foot inside. Never had any need to. Now she ran up the stairs as if she were coming home.

Going to Morris Library filled her with a purpose that seemed worth primping for. Besides, she knew there'd be mostly young people there, and she still had enough vanity in her not to want to be seen as old.

"I've forgotten, but where is the travel section?" Tessie asked the young woman behind the front desk. "One flight up," she answered, without looking up from her filing.

Approximately 449,280 minutes after her father died, Dinah Lockhart brought home a letter that her teacher had written to her mother. The word PERSONAL was written on it in small block print

.

"What's this?" Tessie asked.

"Who knows?" Dinah shrugged, as her mother took a kitchen knife and slit open the envelope.

Dinah knew. It was a letter from her seventh-grade teacher, Mr.Silver.

Tessie read each word carefully, her lips moving imperceptibly.

Dinah watched her mother struggle with the words, holding the note, written on lined loose-leaf paper, at arm's length. She could see the vein over her mother's left eye start to pulse, the way it did when she felt anxious.

"'. . . crying in class . . . distracted and disinterested . . . the seriousness of the situation . . . our recommendation that you seek counseling for her . . .'"

Tessie had noticed how Dinah talked in a monotone voice and how she never seemed to be completely there. But she hadn't connected it to the truth: that Dinah was lost. No friends, no language to put to her feelings, no way to help herself. "Distracted and disinterested," Mr. Silver had said.

"You cry in class?" she asked her daughter.

"Yeah, sometimes."

"How come?"

"Can't help it."

Tessie stared at her daughter, her beautiful thirteen-year-old daughter with the red ringlets and shiny face, and saw the pleading eyes of a child about to be hit. She was not a woman likely to make hasty decisions, but as she read the teacher's words, she was struck by one unequivocal thought: We have got to get out of here.

Tessie knew without knowing how that leaving Carbondale was the right thing. She couldn't spend another day selling dresses at Angel's. The smell of cheap synthetics filled her breathing in and out, even when she wasn't in the store. Only the taste of Almaden Chianti could wipe it out. The sweet grapey Almaden, which she had taken to buying by the case, was her gift to herself for getting through another day of assuring customers that "no, you don't look like a gosh darn barn in that pleated skirt." Just four sips. She'd have four sips as soon as she came home from work. Right before dinner, there'd be another four sips and a couple more during dinner, and so the Chianti got doled out through the evening in small, not particularly worrisome portions. It got so that she was finishing a bottle every other night. When she'd go to buy another case at the liquor store, Mr. Grayson always greeted her the same way. "Howdy do, Tessie. You wouldn't be here for another case of Almaden Chianti, would you?"

Embarrassed that he noticed, Tessie would bow her head and pretend to be making a decision. "Hmm, sounds like a good idea. Might as well have some extra on hand for company." Of course the last time Tessie had had company was back when Jerry was alive.

We have got to get out of here. The words moved into Tessie's head, each letter taking on a life of its own–arches, rolling valleys, looping and diving until they sat solid like gritted teeth. She thought about their desolate dinners–macaroni and cheese or one of those new frozen meals. She'd ask Dinah how school was. "Fine" was always what she got back. Then she'd claim to have a lot of homework. Tessie would light her after-dinner cigarette, and the two of them would retreat to their rooms. Tessie's only solace was talking to her dead husband. "What she needs is a fresh start," she would whisper to Jerry. "What we both need is a fresh start."

We have got to get out of here. The sentence buzzed inside her like a neon light.

Tessie and Jerry Lockhart had spent their honeymoon in St. Augustine, Florida, seventeen years earlier, in 1941. It was the only time in her life that Tessie had ever left Carbondale. The memory of that had all but faded except for the sight of Spanish moss draped over live oak trees like a wedding veil. She had never seen anything so beautiful.

Although the ads for Florida always claimed that it was so, she never really believed that it would be warm enough to swim in the ocean at Christmastime–until she was there, and then it was. So different from Carbondale, with its gray winters and ornate Victorian houses always reminding her what was out of reach.

She checked out every book about Florida that was available in Morris Library. She balanced the giant atlas on her knees and, using St. Augustine as the starting point, made a circle with her fingers north to Jacksonville, west to Tallahassee, and south to Sarasota. As she leafed through the reference books and read about the cities on the map, she found herself staring at pictures of Alachua County, swampy Alachua County, where the sun shining through the moss- covered oaks cast a filigree shadow on the boggy earth. Alachua County, whose name came from the Seminole-Creek word meaning "jug," which referred to a large sinkhole that eventually formed a prairie.

"What a beautiful place," she thought to herself, pushing aside any doubts about an area that was essentially named after a sinkhole. Then she read that Gainesville, in the heart of that county, was home to one of the largest universities in the United States. Pictures of the redbrick Century Tower at the University of Florida reminded her how much she liked being part of a college town. It gave her status, she thought. People in Carbondale assumed other people in Carbondale had been schooled there, or were in some way a part of the university. She liked the exposure that Dinah got to higher education, and it thrilled her that Dinah might be the first in their family to go to college.

Could Gainesville be the place? she wondered.

Just by asking the question, she knew she'd already answered it.

That night she would tell Dinah how they would leave by Christmas and that she would begin 1959 in a new school.

Dinah Lockhart never made a precise effort to tally up the number of cigarettes her mother smoked each day, or how many minutes it had been since her father's death. She knew these things instinctively, the way she knew to avoid stepping on cracks and knew to lift her feet and make a wish whenever her mother drove over railroad tracks. She wasn't superstitious exactly, but why risk it?

Things had been taken away from Dinah, so the things that were there counted. Things like the fourteen honey-locust trees and sixty-two squares of sidewalk on her block.

Excerpted from Orange Blossom Special © Copyright 2012 by Betsy Carter. Reprinted with permission by Dell. All rights reserved.

Orange Blossom Special

- paperback: 296 pages

- Publisher: Dell

- ISBN-10: 0385339763

- ISBN-13: 9780385339766