Excerpt

Excerpt

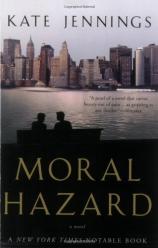

Moral Hazard: A Novel

Chapter One

How would you have me write about it? Bloody awful, all of it.

I will tell my story as straight as I can, as straight as anyone's crooked recollections allow. I will tell it in my own voice, although treating myself as another, observed, appeals. If I can, no jokes or jibes, no persiflage -- my preferred defenses. I'd rather eat garden worms than be earnest or serious. Or sentimental.

I recount the events of those years with great reluctance. Not because you might think less of me -- there is always that. No, the reason is a rule I try to follow, summed up by Ellen Burstyn in the movie Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore: "Don't look back. You'll turn into a pillar of shit."

See? I can't help it. Wisecracking -- a reflex. I've lived in New York for several decades, but I was born in Australia, where the fine art of undercutting ourselves -- and others -- is learned along with our ABCs. Australians -- clowns, debunkers.

I have to start somewhere, so it might as well be with Mike.

I met Mike -- beanpole Mike, angular and awkward as Abe Lincoln and looking a little like him -- in Pasqua, a coffee shop in the World Financial Center, downtown in Battery Park City. Long gone, replaced by a Starbucks, Pasqua was popular with the bankers, traders, analysts, lawyers, and back-office types who worked in the center's towers because the coffee was heavy, viscous, bitter -- a powerful propellant. Not to be trifled with. Drink enough Pasqua coffee and you were orbiting.

Mike was standing behind me in the impatient, early morning line that tailed out the door. I ordered a large black, and he said, speaking over my shoulder to the young man behind the counter, "Same for me," to save time.

"Diesel fuel," I said, conversationally, but staring ahead, as New Yorkers do, so as not to be intrusive.

"Liquid amphetamine," he replied.

Amphetamine? The phrase "amphetamine activists," from the sixties, somehow emerged from the recesses of my mind. I sneaked a look at him, taking in his large nose and tufty hair and thought, My age, ugly as an eagle. I faced the counter again.

Through the window, across the damp plaza, last passengers were leaking from the Jersey ferry, heads bent against the puncturing cold, coats buttoned, scarves wound tight, gloved hands holding bags and briefcases or thrust into pockets. The Hudson was in a bleak mood, turned in on itself, indifferent, with scraps of ice bunched at the edge, driven there by the current.

Our paths crossed again several days later because, as it turned out, we both worked for Niedecker Benecke, the investment bank. You will know it: not quite top tier but bumping against Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, and Morgan Stanley. At the time -- the winter of 1993–1994 -- financial services companies were shrugging off the recession induced by the excesses of the eighties and ramping up for the excesses of the nineties. Corporate raiders and junk-bond peddlers -- Mike Milken, Ivan Boesky, Carl Icahn -- were the past. Joseph Jett, Nick Leeson, the Asian meltdown, CNBC, irrational exuberance, the 10,000 Dow, the dot-com boom -- that was to be the future. As was the dot-com bust, the obliteration of the World Trade Center, recession, fear. Dragon's teeth sown.

I was writing a speech on derivatives for Niedecker's general counsel to be given at a gathering of an international regulatory body in Japan. Hellishly complicated, computer-generated financial contracts, derivatives are the brainchildren of those math pointy-heads known, in Wall Street lingo, as "quants"'from the word "quantum," I'd guess. Derivatives and the regulation of them were particularly contentious in the early nineties, although, as one old-timer commodities trader told me, sniffily, they'd been around, in one form or other, since the Sumerians. "Once upon a time, it was commodities, then futures, now derivatives," he'd opined, delicately shooting his cuffs. "It's all structured finance. It's all aimed at neutralizing risk by parceling it up, selling it to someone else. Quanting around, nothing new in that."

The general counsel ordered me to research views within Niedecker on derivatives, including those of the head of the risk-management unit. That was Mike. A math pointy-head himself, he had the job, in part, of monitoring the activities of the firm's quants. Heaven knows, nobody else in executive management had a clue what they were up to.

I knocked on the frame of his open door. "We have a two-thirty." In true corporate fashion, I was left to flap on the threshold, drying, waiting for him to acknowledge me. An interminable minute passed. Mike took a last look at the screen of his computer and in a single, abrupt movement was at the door, hand extended.

"I remember you. The coffee shop."

"Yes."

You're from Communications, right? A speech for--?" He named the general counsel, famous among unyielding men for being unyielding. "Writing for him, huh? What did you do wrong?" Laughed, high up, in his nose.

I explained the speech, switched on my tape recorder, and asked my dutiful questions. We covered the Group of Thirty recommendations for derivatives regulation, the GAO response, the Basle Agreement. He gave the standard financial industry arguments. Derivatives are risk-management tools, nothing but beneficial, a boon to investors and the economy. To regulate them would be to hinder the flow of money, disrupt the global good. Et cetera.

Mike's answers were peculiarly without enthusiasm. For the most part, when Communications personnel come calling, corporate henchmen are all smiles: upbeat, encouraging, patient. And no doubt sigh with relief once we are out of sight. One can never be too careful.

Mike was unusual in another respect: he didn't use jargon or clichés. Agent Orange words. "Liquidity" and "transparency," yes, but not "going forward," "pro-active," "paradigm," "incentivize," "added value," "comfort level," "outside the box," "a rising tide lifts all boats." He didn't even use "fungible," a word that was enjoying a big vogue. So I ventured a last, offhand question. "What do you really think of derivatives?" Worth a try. He quickened. "The mathematics can be awesome. You have to admire the mathematics. And they can be an excellent risk-management tool ..." He trailed off, obviously wondering whether he should continue. "Well, it helps to look at derivatives like atoms. Split them one way and you have heat and energy'useful stuff. Split them another way, and you have a bomb. You have to understand the subtleties."

Understand the subtleties. God is in the details. Cracks me up.

Moral Hazard: A Novel

- paperback: 192 pages

- Publisher: Harper Perennial

- ISBN-10: 0007154623

- ISBN-13: 9780007154623