Excerpt

Excerpt

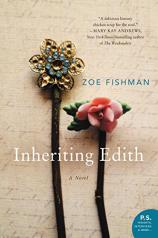

Inheriting Edith

Chapter 1

A beach house,thought Maggie, her head spinning like the revolving glass door that deposited her back onto Eighteenth Street. People headed home after work bumped and jostled along the sidewalk as she slipped in unsteadily.

“A house in Sag Harbor.” Just the words Sag Harbor conjured up images of the kind of life she had never known. Sand dunes and waves; sea grass and farmers’ markets; rich women with their sun-kissed faces stretched tight like rubber bands.

“Are you sure?” she had asked incredulously when the lawyer had told her upstairs.

“Yes, Miss Sheets,” he had replied brightly. “Here it is, plain as day,” he explained, tapping the will with his finger. “She wanted you to have it.”

Maggie shook her head, still not believing him. They hadn’t spoken in over four years. It made no sense.

“Sag Harbor is lovely, Miss Sheets. A beach town with a New York mentality.”

“Oh, do you have a house there?” she asked, not really caring if he did.

“No, we have a place upstate. My wife hates sand.”

Maggie had nodded absently, thinking that hating sand said a lot about a person. She had to hate sand on principle, because of the way it crept into every uneven ridge of a hardwood floor; collected in grainy, wet piles in the bathtub and settled in the rumpled ridges of bed sheets. It was impossible to clean. But to hate it as someone who didn’t clean houses for a living, who probably employed someone just like Maggie to do it for her, that implied something else entirely.

“But back to you,” he continued, “and Sag Harbor. The house comes with something.”

“Something?” Maggie asked.

“Or someone, I should say.” Maggie’s stomach dropped. Of course.

“Her mother.”

“Yes, yes—so you know Edith?”

“Know? No, I wouldn’t say that. We met once.”

“So you know that she had been living with Liza when she passed.” Passed, thought Maggie. Liza had killed herself. Passed was not the right word, not even close.

“Yes, I know.” Maggie looked down at her feet, thinking about Edith. What must it be like for her now, she wondered, in the aftermath of her daughter’s death? Maggie hadn’t exactly been a fan of Edith’s—she had treated her like the help at the one lunch they’d shared, despite Liza’s repeated attempts to clarify the fact that they were friends—but no mother deserved her child dying before she did. The lawyer clasped his hands in front of him on the desk.

“Edith has recently been diagnosed with early stage Alzheimer’s,” he announced.

“Oh no,” said Maggie. “I had no idea. Liza and I . . . we hadn’t spoken in some time.”

“Yes, apparently the diagnosis was quite recent. Two months ago, to be exact.”

Maggie rubbed her temples, overwhelmed. “I’m sorry, isn’t there a family member better suited for this?” she asked. “I clean houses, Mr. Barnes. I don’t— I’ve never cared for an elderly person. I don’t have the first clue about it.”

Maggie’s mother had been dead a long time, and her father had begun a new life with new kids shortly thereafter. She’d never even seen either of them old, she realized, much less cared for them. She thought back to all of the times Liza had scolded her about her financial recklessness; her relationship decisions; her lack of ambition; the fact that she wore a denim jacket in February. Why would she choose her for this?

“No, I’m afraid not. Edith is the only remaining member of Liza’s immediate family, and as an only child she had no siblings.”

“And what if I don’t take the house? What happens to it? And Edith?”

“The house goes on the market and Edith goes to an assisted living facility nearby,” he answered.

“And Liza didn’t want that.”

“No.”

Maggie wondered when Liza had written the will, and whether or not she knew that she was going to kill herself at the time. She felt a stab in her heart, imagining Liza sitting at her desk in her old apartment, making the decision to bequeath everything to Maggie of all people, snacking on her fluorescent orange peanut butter crackers, the crumbs of which always ended up everywhere, and sipping from one of her Diet Coke cans that always left impossible to erase rings in their wake.

“Liza, would it kill you to use a coaster?” she had asked once.

“Yes, it would kill me,” Liza had replied, not looking up from the book she was reading on the couch as Maggie stopped mid-vacuum to point out the ring of condensation on her coffee table. Maggie’s choice of words seemed so thoughtless now.

No mutual friend had called Maggie to alert her of Liza’s death—there were none of those four years after their friendship had ceased to exist. Maggie had read about it online, scrolling through headlines in bed.

For days Maggie had wandered through her life like a visitor, her head like a tethered balloon, filled with memories. And then, the voicemail from the lawyer, telling her to come in, that he had news. She still couldn’t believe it—any of it. Liza had known so many people. Why had she chosen Maggie for this? Maggie supposed it could be her way of apologizing, but it was so dramatic, so beyond what the situation called for. But who even knew if it was an apology at all?

Regardless of Liza’s intentions, there was no denying what this offer meant. A paid mortgage and a monstrous stipend that would last far beyond the foreseeable future. Security for her daughter, Lucy. Cleaning houses to support herself was one thing—to support two and pay for childcare was quite another. It had been hard, since Lucy had been born, there was no denying it. Maggie thought about the beach; sand between her toes and Lucy giggling as she ran from the shoreline, the waves crashing behind her. It would be a nicer life there, for Lucy. Easier.

And there would be no more housecleaning, except for her own. She’d begun to resent her job lately. Scrubbing floors while she paid for someone else to watch Lucy didn’t make sense. In terms of financial freedom, Liza’s offer was akin to winning the lottery for Maggie.

And yet, the winnings included an uptight old lady who Maggie would have to play nursemaid to. It also meant uprooting their lives to live in a place where they knew no one; and more than that she would be submerging herself in the sadness and guilt Liza had left in her wake. Maggie didn’t believe in ghosts, but the remorse she felt about her friend’s death already felt like being haunted, even at a safe distance. Across the street, the light flashed Don’t Walk, but Maggie, glancing both ways quickly, darted across the intersection anyway.

Maggie had met Liza ten years before, when she was twenty-eight. A lifetime ago, now. She had just begun working for the agency, just started to clean houses for a living, which on paper she knew seemed really sad for a college educated woman, but in reality paid her bills far better than her desk job ever had.

It was fancier even than she had initially thought, the agency she worked for, catering exclusively to rich people with deep pockets. Maggie enjoyed the work, much preferring hard labor to sitting in a chair all day, her ass growing as she indulged in the endless supply of stale leftover Danish and soggy pasta salad from the steady stream of meetings in the conference room across from her. Plus, there was tremendous satisfaction in knowing that even the wealthiest people were dirty behind closed doors.

She’d been excited to know she was going to the world-famous author Liza Brennan’s Upper West Side penthouse. And it was just as she expected, with its built-in bookshelves crammed to bursting, its expensive artwork and French cotton bed sheets as soft as silk. There was nothing fussy about her apartment, but it looked expensive nevertheless. Liza had good taste. She bought the things Maggie would have bought, if she had had the means.

When she had first begun cleaning it—once a week on Thursday mornings—Liza would greet her and then leave, her laptop and papers peeking out of her navy leather satchel. Soon, though, she had asked if Maggie minded if she stayed— her focus was hopeless at coffee shops, she admitted—and Maggie said of course, she didn’t mind, although truthfully she did. As a rule, she hated when her clients hung around, watching her every move, making sure she wasn’t snooping or half-assing it. But Liza was different. She kept her eyes on her computer or the book she was reading without so much as glancing Maggie’s way. It made her want to work harder, that trust. And she had.

“I could eat dinner off this floor,” Liza had remarked, when Maggie bid her farewell, her small cart of cleaning supplies in tow. “Thank you.” And then she would hand Maggie a fifty-dollar tip without so much as a flinch.

Maggie walked around the perimeter of Gramercy Park; the wrought-iron fence separating the plebeians like herself from its impeccably groomed grounds and residents. Was plebeian the right word? she wondered. Liza would have known.

A few months in, she and Liza began to talk. “What’s your story?” Liza had asked one morning, startling Maggie, who was scrubbing Liza’s sink in yellow gloves up to her elbows. Her hands were as dry as driftwood, with cuticles as flimsy as tissue paper. No way around it in her line of work, but the gloves helped.

“My story?” she had replied.

“Yeah, how’d you end up cleaning apartments? You don’t exactly seem like the toilet scrubbing type.”

Maggie wasn’t one for sharing much of anything about herself, but there was something about Liza that made her feel at ease, something familiar. They became unlikely friends. Until they weren’t.

Maggie hustled past the bodegas and the thrift shops; the wine bars and the bar bars; the Peruvian place; the Chinese restaurant; the nail shop where she had once had her eyebrows waxed into commas.

“Hey, Jose,” greeted Maggie, her voice cracking.

He looked up from the tiny black and white television perched on the table beside him and nodded. Once July hit, Jose would emerge from the basement apartment he had owned for close to forty years and take up a daytime residence on their stoop. Sunup to sundown, he sat in his green folding chair and watched baseball in his shorts and V-neck T-shirt; his bald head and forearms were brown by the time September rolled around.

She took the four flights of stairs two at a time, panting as she got higher. At her door, finally, Maggie turned the key, only to have the chain abruptly stop it from opening.

“Mommy!” bellowed Lucy.

“Hey Miss S.,” said Dahlia, unlocking the chain. Lucy sprang forward like an Olympic sprinter, attaching herself to Maggie’s legs with unbridled glee. A delicate flower, she was not, her daughter. “Lucy’s been real good. Had her snack, played with some puzzles—”

“Sesame!” Lucy shrieked, interrupting her.

“Yeah, we watched a little bit,” admitted Dahlia.

“It’s okay. She’s a handful today. I get it.” She pulled her wallet out of her bag and handed Dahlia her pay, noticing that she only had two twenties to last through the rest of the week.

“Thanks, Miss S.” Dahlia folded the cash into a neat U and slid it into the back pocket of her shorts. “Bye Lucy.”

“Bye Dawwa,” replied Lucy. “Hug!”

Dahlia laughed and bent down. Lucy pulled her head close, like the Don of Avenue B, and then released it, pleased with the blessing she had bestowed and ready to move on to the next order of business.

As Dahlia slipped out the door, Lucy galloped around the apartment, neighing. Maggie noticed for the millionth time just how much she looked like her father. The blond curls; the brown eyes; the dimple that had gotten Maggie into trouble in the first place.

“How was hanging out with Dahlia?” asked Maggie. “Did you guys play horsey?” she asked, collapsing onto the couch in a sweaty heap as Lucy climbed onto her lap. Once settled, she drank from her sippy cup of milk in silence, crossing her chubby legs in contentment.

“You sad, Mommy?” she asked.

“Yeah, I’m sad.”

“About that lady?”

“Yeah.”

“Where she at again? She died?”

“Yes, baby, she died.”

The morning after reading about Liza, Maggie’s eyes had been red and swollen from her tears, so much so that she could barely open them. When Lucy had asked her what was wrong, Maggie had had no time to concoct a sensitive story about the circle of life.

“My friend died,” she had told her, surprising herself with the word. She hadn’t considered Liza a friend in a long time.

“What’s ‘died’ means?” Lucy had asked.

“Gone.”

“Oh.”

She had patted Maggie on the hand and returned to her favorite activity—lining up her parade of tiny plastic zoo animals—as Maggie stared blankly out of their lone window into her neighbor’s empty kitchen, exhausted.

Maggie looked around the room now—the puzzles and crayons, the threadbare rug, the Ikea kitchen table and chairs she had bought when she was fresh out of college—and sighed. She looked at her hands, as dry as chalk.

She thought about Liza; what her advice would have been had someone else left Maggie their home and mother.

What’s the problem here?Liza would have asked.

But the mother—Maggie would have argued.

So what about the mother? How hard can making sure an old lady takes her medication be? If you don’t take this offer, you’re an idiot. It’s a once in a lifetime opportunity.

And then she would have moved on to another topic of conversation. Maggie could take her advice or not, it was up to her. That was how their relationship had worked, until it didn’t.

So this was Liza’s final piece of advice. Take my house and mom, take Lucy out of that tiny apartment in that crazy city and start over. Maggie didn’t like being told what to do usually, but this was different. Since Lucy had been born, she had felt like she was drowning, slowly but surely, the water inching up all around her.

And so she would.

Chapter 2

Edith woke. Blinking in the darkness, she knew even before turning to the clock on her bedside table that it was

5:22 am. Her body, stubborn old thing that it was, would not sleep a minute more. The world outside her bedroom windows was silent, but soon the birds would begin their inquisitive chirping; the bugs their interminable buzzing and the twenty-somethings their incessant shrieking and splashing in the pool next door. It was the middle of summer, but Edith wished it was the end.

Every year it was the same. Spring would arrive, timidly at first—a daffodil here, a crocus there, an unexpected sunburn across the bridge of her nose while she was out walking—and then, right behind it: people. So many of them, in their shiny cars filled to bursting with designer weekend bags and organic snacks; the women’s tresses highlighted just so and the men’s receding hairlines artfully disguised, their children spilling out like groomed monkeys. Edith despised them. Sag Harbor was her home year-round—through the sunshine and the snow, the open windows and the grumbling furnace—but these people, these were quite literally fair-weather friends.

Edith stretched carefully, wincing at the papier mâché– like stiffness of her eighty-two-year-old joints. It was hard, this aging thing, especially since her body had once been as limber as a rubber band. She had been a dancer when she was young; her body her instrument. Now it felt more like an old car, with a faulty transmission. The wrinkles that rippled out from the corners of her eyes and across her cheeks and forehead like the waves of a pond didn’t bother her as much as the fact that her body just wouldn’t move like it used to, stalling out when she least expected it. Bending over and getting up hurt now, and stairs were best avoided, but she wasn’t going down without a fight. She made herself walk every morning, no matter how difficult it was. She was still the boss of it, thank you very much. And her mind, too, no matter what that fancy doctor in Manhattan said, in her condescending and nasally voice.

Irritating or not, she had scared her, and so Edith took her pills every morning before brushing her crisp white bob, donning her khaki Bermuda shorts and sleeveless chambray blouse, slipping into her sandals and climbing into her car to drive the short distance to the beach, where she strolled the shore for twenty-five minutes precisely. She loved the way her muscles responded to the soothing lap of the waves against her feet, unfurling like flags to remind her of their strength, and the way the sun hung hesitantly in the sky, groggy from a night’s rest. It was her favorite time of the day.

After she had found Liza, Edith had foregone her morning ritual, instead hiding in the house with the lights dimmed and the shades drawn—an informal Shiva if there ever was one. She was the world’s worst Jew, hadn’t so much as thought about the religion her mother had tried to impress upon her as a child unless she saw a particularly inviting looking loaf of challah at the supermarket, but then, in the aftermath of such awfulness, it suddenly felt like second nature. There was no Rabbi, but the door was open and people who had known and loved Liza had come through, heaping gelatinous looking casseroles and lopsided cakes on the kitchen counters.

Normally, Edith was not one to dwell on her emotions, whatever they were, but this was a sadness that she had never felt before. If only she hadn’t done this or said that to Liza; if only she hadn’t been so judgmental and impatient; if only she’d been a different kind of mother altogether. Her mind raced back and forth, on a hamster wheel of guilt.

The lawyer had called and called, leaving message after message on the machine for the next two weeks, but Edith could not be bothered. He had had Liza cremated, as per the will that he had helped her draw up, and that was all that she needed from him as far as she was concerned. She wasn’t ready to hash out the copious details of her daughter’s life with anyone yet, much less a total stranger.

And then he had shown up, at her doorstep, his suit wrinkled from the ride. Edith wished she hadn’t answered the door, but she was a practical woman, even in her grief, and knew that she couldn’t avoid her daughter’s wishes forever. She had laughed in his face when he told her that the cleaning lady had inherited the house, and that she and her daughter would be moving in to look after her. The cleaning lady!

“Over my dead body,” she had replied.

“I’m sorry, Edith, you don’t really have a choice. Well, you do, but it would involve moving out and relocating to an assisted living facility. Liza has provided the necessary funding for that. It was her house, after all.” He laughed awkwardly—a half laugh that sounded more like a cough. As much as she wanted to wring his skinny little neck, it was true.

“Mom, you can’t live on your own anymore,” Liza had told her matter-of-factly after Edith had taken a tumble in her pink tiled bathroom five years earlier; the same pink tiled bathroom that Liza had grown up using.

And so, Edith had moved in with her daughter, kicking and screaming, until she had realized that living there wasn’t all that bad. It had taken her a while to get used to what Liza had called their tree house because of the open floors and upside down layout, with the kitchen and living room on the second floor, but soon she had fallen in love with its conflux of light and air amongst the green leaves outside their windows. It soothed her.

She and Liza had developed a real friendship, or so Edith had thought. Now it was clear that she had not been her daughter’s friend at all, but instead, a burden to be passed onto someone who had no other options. She felt like a fool.

Edith had wrestled with the lawyer’s news for a day or two, sitting on the couch and thinking as her sadness turned into anger. How dare Liza insinuate that she was incapable? Edith had started over before, had overcome obstacles her daughter didn’t even know about, and she could certainly do it again without unwanted help from a stranger.

There was no way in hell she was leaving. So she had forgotten things a few times. She was eighty-two years old for God’s sake! She hadn’t been sleeping well, that was it. Lack of sleep had always made her forgetful. As far as falling now and again, so what? She would wear one of those MedicAlert bracelets gladly if it meant keeping her independence.

And just who was Liza, thinking that her word was more credible than Edith’s? Liza wasn’t well; hadn’t been well for years—the proof obvious. You didn’t do what she did if you had your senses about you. She would contest the will, she decided. But figuring out how exactly would require time and money, and she certainly didn’t want to leave this house, the house that was rightfully hers, while she did so. She would stay.

So here she was. The evening before, Edith had said hello when Maggie had arrived with her sleeping toddler in her arms. The movers were coming the next day, she had told her. Edith had nodded, showed Maggie Liza’s bedroom, and retreated to her own, where she had holed up with a small glass of whiskey and a plate of cheese and crackers. She’d eaten on her bed and washed the dishes in her bathroom sink, feeling vaguely like a prisoner, but not minding it too terribly much. The alternative—engaging in forced conversation and pretending to not be furious—seemed unnecessarily exhausting.

Now, what if they were awake and wanted to talk to her? Before her coffee? Hopefully Maggie had some common sense. She’d certainly had enough sense to glom onto Liza anyway, and reap her friendship’s rewards: no rent and money to cover whatever utilities and expenses cropped up for a good long while, if not forever. The only wrench in the works, at least from Maggie’s perspective, Edith figured, was of course her. The crotchety old lady who didn’t live in a shoe like the nursery rhyme suggested, but instead, came with the house, like a goddamn appliance or something. Edith was so mad at Liza that she could spit. You could do that, Edith had discovered—miss and despise someone at the same time.

The three bedrooms of the pagoda-style house were on the first level; the kitchen and dining and living rooms were on the second. On the outside, its red wood and white stone exterior peeked out from the dense, green foliage with a porch that wrapped around its second floor, hugging the floor to ceiling windows like a belt. There was a tiny guesthouse— more like a box, really—that Liza had used for her writing, and a pool, too, that she had sometimes swum laps in when she had been in one of her fitness phases.

Edith smoothed the white coverlet of her bed and surveyed her room. She had never been much for fuss: there was her bed, a study in crisp white linen; a bedside table upon which sat a bookmarked paperback mystery and a brass lamp; a blue velvet chair that looked inviting but wasn’t; and a maple bureau, over which hung a small mirror. Attached to her bedroom was her bathroom, which boasted a long stainless steel rail around its perimeter, along with two smaller ones in the shower. Liza had had it updated for Edith, but Edith hated it. She felt like she was taking a shower in a subway station.

She closed the door behind her. This was her territory now, small as it was, and she would protect it. Besides, who knew what a two-year-old would do to her bedspread? She shuddered, imagining tiny strawberry jam handprints all over it.

In the hallway, she paused to listen, grateful for silence. Good, she was the only one awake. She ascended the stairs carefully, leaning on the banister with more weight than she cared to admit as the rising sun cast a purple light through the trees.

In the kitchen, Edith set about making her coffee, frowning slightly at the new snacks that sat at the corner of one of the long marble counters, wedged between the toaster and the wall. Graham crackers and tiny yellow goldfish; bananas and shiny red apples inside a green ceramic bowl. Her green ceramic bowl. She poked it, thinking, Mine.

As the coffee percolated, she willed her own inner child away, knowing that these types of thoughts, about the ownership of bowls, were infantile and useless. She had always been terrible at sharing. Edith startled suddenly, hearing footsteps creak up the stairs behind her.

“Good morning,” a soft, clear voice announced.

Edith took a deep breath and turned to face Maggie, taking in her ragged tank top and ripped pants; the fact that she wore no bra. Liza had always swaddled herself in layers of colorful silk and chiffon, like a plump parrot, so it had been some time since Edith had seen the female form like this—in all of its honey-hued glory.

“Did you sleep well?” asked Maggie.

“Yes, thank you. And you?” The beep of the coffee machine shattered the tension, and Edith, grateful for something to do, held her red coffee mug up in an awkward salute.

“Very well, thanks,” answered Maggie.

“And what about little— Forgive me, what’s your daughter’s name?”

“Lucy. Lucy had a bit of a tough night, what with it being a new place and all. She ended up in my bed. Practically pushed me out of it. She’s a spreader.” Maggie flung her arms over her head in demonstration. Edith knew she should smile, nod in understanding, but she didn’t feel like it.

“You know, I’m happy to make the coffee for you, Edith. I can set it up the night before, no problem. Does it have a timer?” asked Maggie, examining it closely. “Oh yes, there it is. Just let me know when you wake u—”

“Why should you make the coffee for me?” barked Edith, cutting her off. “I’m perfectly capable of making a pot of coffee, Maggie.”

“Suit yourself,” said Maggie.

“I’m not sure what that ridiculous lawyer told you, but I don’t need your help.”

“Message received,” said Maggie. She turned to face the cabinets. “Is the sugar in here?”

“Yes,” answered Edith. “And the milk is in the refrigerator.”

“Thanks,” said Maggie. Edith glared at her back as she prepared her cup.

“So,” she said, turning around.

“So,” repeated Edith.

“If you’re looking for a fight, you’ve got the wrong girl,” said Maggie, before taking her first sip. “I’m just as surprised as you are that Liza chose me.”

Edith raised her mug to her mouth and took a sip of her own, not knowing what to say.

“But she did, and I’m here, so I think we both just have to deal with it, Edith. And being rude isn’t exactly a productive way of dealing with it.”

“Excuse me?” asked Edith.

“Come on, Edith, I know you’re angry about the situation. I would be, too, if I was in your shoes. But I am sincerely here to help you, you know. As best I can, anyway. We can stay out of each other’s way until that kind of opportunity presents itself, if you like. But consider yourself warned— staying out of the way of a two-year-old is tough.”

“Maggie, I don’t appreciate being spoken to like this,” said Edith. “Not at all.”

“I mean no disrespect, believe me. I just thought it would be easier to put our cards on the table.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Edith replied.

“Okay, I get it. I’m not going to bully you into admitting your discomfort.” Maggie walked over to the table and pulled out a chair. “I guess it’ll just happen when it happens. Forget I said anything.”

“Is that supposed to be some kind of a bad joke?” asked Edith.

“What?”

“Forget you said anything? Are you making a joke about my Alzheimer’s?”

“Oh, God no, Edith, please, I would never. I meant it figuratively—”

Edith stormed past Maggie and down the stairs, a furtive smile on her face. Of course she knew that Maggie hadn’t meant anything by saying that, but it felt good to scare her a little. Maggie had surprised her with her forwardness. Edith had been expecting a meek mouse, not a pit bull.

Downstairs, Edith grabbed her keys from the slim wooden table that hugged the wall in the narrow hallway.

“Mommy?” a small voice from Liza’s bedroom called out. Edith froze, glancing at the clock.

Already she was twenty minutes behind schedule. Engaging with a toddler would set her back at least twenty more. Soon her normally deserted beach would be plastered with the yoga mats of those smug, supple people; its sand flying under the hooves of the gazelle-like runners she always made sure to avoid. Not to mention the brighter sun, which would pink up her skin like a boiled shrimp. She turned as quietly as she could towards the door and then, of course, dropped her keys, which landed in a loud, jangled mess at her feet.

“Mommy!” the voice demanded, now outraged by the injustice of being ignored.

Edith retrieved her keys and looked up, willing Maggie to hear her daughter, but knowing that she probably wouldn’t. She could either ascend the stairs again and alert her to the fact that her child was awake or handle it herself. She walked towards the voice instead and gently pushed open the door, which was not entirely shut.

In the middle of a sea of rumpled white sheets was a very small girl swaddled head to toe in pink striped pajamas that zipped up the front. Her curly blond hair pointed north, south, east and west all at once. She regarded Edith coolly, as though a strange old lady appeared in her doorway every day.

“Good morning,” greeted Edith formally. The girl blinked back at her. Edith had forgotten her name again. “Your mother is upstairs, getting breakfast ready,” she continued. “I’m Edith.”

“Edith,” she repeated, tilting her head slightly. And then, “Woommay.”

“Yes, that’s very nice,” replied Edith. “I have to be going now. Do you need help out of bed?” She moved towards her and extended her hand.

“Woommay,” the child said again.

Maybe she’s telling me her name, thought Edith, although it didn’t sound familiar. She’d always had a hard time remembering names, even when she was young. If indeed it was her name, it was a strange one, but all of the names she heard these days were. Whenever she got her hair cut at the salon in town, she would thumb through magazines of celebrities toting children named things like Apple and Moon. It was absurd.

“Hello Woommay,” she said now. “I’m Edith.”

“No! Woommay!” the child yelled, switching from docile lamb to Bengal tiger cub in a matter of seconds, reminding her of Liza as a toddler in the process. Edith backed away slightly as Maggie appeared in the doorway.

“Lucy!” she reprimanded. “That’s not how we speak to

people. Apologize to Edith.” Lucy, thought Edith. Lucy’s face crumpled like a Kleenex. “Sorry Edith, she’s just a little disoriented, I guess.” Maggie

scooped her out of the bed and held her on her hip. Lucy’s

lean, striped legs curled around her mother like parentheses. “Oh no, that’s quite alright. I understand.” “Woommay,” Lucy whimpered again. “Yes, this is Edith. Your new roommate.” At the correct

translation, Lucy’s face unfolded into a spectacular smile, her brown eyes twinkling. “Ah, roommate!” said Edith. Roommate. As though the three of them were sharing a dorm room in college.

“That’s an impressive word, Lucy,” she offered. Lucy nuzzled her face into Maggie’s neck, pleased. “Well, I better get going,” Edith continued.

“Of course, go ahead,” said Maggie kindly, as though their

kitchen confrontation had never happened. “Bye woommay,” said Lucy. “Goodbye Lucy.” Edith nodded and saw her way out.

Inheriting Edith

- Genres: Family Life, Fiction, Women's Fiction

- paperback: 320 pages

- Publisher: William Morrow Paperbacks

- ISBN-10: 0062378740

- ISBN-13: 9780062378743