Excerpt

Excerpt

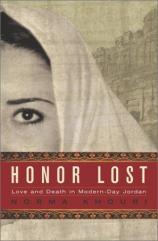

Honor Lost: Love and Death in Modern-Day Jordan

Chapter One

The cluttered break room in the back of N&D's Unisex Salon was not much to look at. Twenty years' worth of scuff marks marred the once-white walls and the tile floor whose warm earth beige once had shone, but which were now a dull yellow-gray. The scruffy brown couch to the right of the door looked like a battered old man, pockmarked by time. But Dalia, my best friend, and I knew the room's true value; to us it was a haven, a sanctuary, the only place where we had the privacy and freedom to share our secrets, hopes, dreams, fears, and disappointments.

That couch was the same one we'd sat on at the age of thirteen when we pledged that nothing and no one would ever destroy our friendship. We were like sisters, born a couple of months apart in 1970. Living as close neighbors in the Jebel Hussein district of Amman, we met at a neighborhood park when we were three and, almost instantly, were inseparable. We each had four brothers and very strict parents. And, despite the fact that we were from different religions -- her family was strict Muslim, while mine was Catholic -- we faced similar obstacles growing up that only strengthened the sisterly bond between us.

Though Jordan is a nation of rich and poor -- the rich living in million-dollar villas and the poor in refugee camps -- our families were part of the comfortable middle class that lived in houses handed down through their families for generations, and fathers who worked at respectable jobs; mine had his own contracting business, Dalia's was an accountant for a large insurance company. But we were not of the class that skimmed the cream of opportunities for women -- the elite who automatically sent their daughters abroad to universities to live and study. Our parents never showed a hint of ambition for us, beyond marriage. By the time we entered our teenage years, we'd decided that we could forge the best future for ourselves by finding a way to stay together. At fifteen, we discovered that Jordanian women were allowed to own and operate beauty parlors, one of the few careers open to them. Higher dreams didn't seem possible. And Dalia and I believed that having our own business would guarantee that we could remain together. So, armed with a plan, we started taking the necessary steps to set up our business.

Our first move was to assure our parents that we were not college material. We easily maintained "C" averages, convincing them that this was the best we could do. In a country where a man's education carries more weight than a woman's, our lackluster performance did not worry either set of parents. Next, we suggested that we enroll in beauty school and, given our bleak college prospects, our families did not object -- in fact they encouraged us to go. So, at eighteen, Dalia and I learned our trade. And, after finishing school and working at several places, we were able to complete our final step. Although we didn't see it at the time, we were already using one of the few powers Jordanian women have: to bend their intelligence and imagination to plotting and planning to outwit men to get what they wanted. We would become masters. It didn't occur to us that the effort we spent on conspiring and manipulation might have been turning us into doctors or software designers. Achievement was in tricking the men who controlled our lives; it was survival in an unequal world, as we saw it.

"You know, I think if we complain a bit longer about working at this salon, our fathers will agree to let us open our own place, if only to shut us up. My father seems ready to agree, how about yours?" Dalia asked me one day, her eyes betraying a hint of conspiratorial glee.

"Mine's getting tired of the complaints. But we'd better be careful; they could decide that we should stop working and stay home. I keep telling them that we love the work, we just hate the working conditions." I laughed.

"Me, too, and I think our fathers will go for it. Look at it from their point of view, they'll have an easier time keeping an eye on us this way." Until we were safely married and under the thumb of our husbands, we'd be watched every day, every hour, by our fathers and brothers.

In the end, we persuaded our parents to invest a small fortune in our salon. Our idea was to renovate a portion of a two-story building owned by my father. No one had used the old, stone-front structure, which was close to both of our homes, for ten years; previously it had served as a warehouse for my father's contracting business. Neglected, covered with graffiti, and boarded up, it was destined for the wrecking ball until our plan salvaged it. In return for the use of the ground floor and as payment for the construction work my father and brothers did, we'd pay a monthly rent. To save some masaree (money), the break room was the only part of the salon we didn't modernize; it stayed as dingy as it was. But, behind its closed door, it was ours.

We were going to be daring and serve a need no other salon in Amman seemed to be serving: both men and women. As long as we were well watched and chaperoned, there was no prohibition against it. We held the grand opening of N&D's Unisex Salon in May 1990. The stone facade had been removed and a glass front put in its place. To us, the interior had been transformed into a mini-palace, with a high, vaulted ceiling. A large crystal chandelier was hung and the walls were mirrored, giving the illusion that the room was double its actual size. The mirrors reflected the chandelier's incandescent bulbs, bringing light to every corner of the shop. A high marble counter ingeniously hid our desk and separated the reception area from our workstations, each equipped with all the top styling tools. To us, this salon was more than just a dream come true, it made us feel invincible and powerful. Our modest little enterprise had turned us into professionals, entrepreneurs -- we'd created our own niche. Though we had to some extent designed our own cage, a better one than what would have been created for us certainly, we were not outside of our families' ever-watchful eye. Dalia's brother Mohammed, assigned as our official watchdog, walked her to work every morning from the day we opened and kept a sharp eye on us through closing time. But nonetheless, we were convinced there was nothing we couldn't accomplish as long as we stuck together.

After the opening, we rather quickly managed to develop a healthy clientele and were good at turning our referrals into regulars. Our great haircuts, we decided, were the secret to our success, along with the friendly atmosphere and our quality customer service. The competing salons credited our shop's popularity to the fact that it was one of Amman's few salons owned and operated by women that catered to a mixed clientele. I've often wondered, if I had known that the decision to open the door to male customers would bring us such heartbreak down the road, would we have done it? I think, yes, we would have.

So, at twenty-five, we were still best friends. We'd kept the promise we'd made to each other years before, always stronger together than apart.

Honor Lost: Love and Death in Modern-Day Jordan

- paperback: 240 pages

- Publisher: Washington Square Press

- ISBN-10: 0743448790

- ISBN-13: 9780743448796