Excerpt

Excerpt

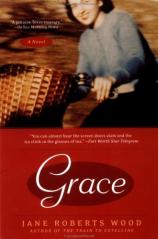

Grace

Spring 1944

Grace Gillian kneels before her hyacinth bed, her bare fingers raking the accumulation of decaying leaves from around the plants. She has long since shucked off her gardening gloves. She loves the feel of the earth's awakening, the humid, fertile smell of it.

Grace is thirty-eight years old. Slender. High cheekbones. Generous mouth. Dark brown hair, almost auburn with the russet highlights around her face. But it is her eyes, soft gray eyes tilting up at the corners, that one remembers. When she reads a poem she loves or when a student makes a perceptive comment, her face lights up and her eyes become radiantly blue. But she does not know she is beautiful. And, although her name is Grace, neither does she think of herself in metaphysical terms, such as, state of. When she thinks of herself at all, it is in sensible, nearly mundane terms—teacher, gardener, friend. But she is neither sensible nor mundane. And on this day, as she rakes the sodden leaves from the hyacinth bed, she is thinking of John, whom she loves beyond the telling. My true, pure love. A love not fueled by desire. This is what she believes. She feels she has long since turned away from desire.

The pecan trees, arching high over her and over her turquoise-colored house, have not yet leafed out. Nor has the elm by the front door. But the magnificent live oak is in full leaf. And a single wild plum and a domestic peach in the northwest corner of her garden are dizzily in bloom, infusing the blue air and the yellow grass with the colors and scents of spring.

A song from the kitchen radio drifts out into her garden. "I'll be seeing you in all the old familiar places," Jo Stafford sings tenderly. Since the War, all the songs are heartrending to Grace. Looking closely at the hyacinth buds, she can faintly discern the color—purple or white—each will become. Colors of mourning.

She, Grace, although not in mourning, is deeply sad. Anna, her next-door neighbor, is sick. Sick to death. When she thinks it again, sick to death, the phrase takes on its literal meaning. Anna is sick, and in a day or two she will go to her death. And then John will leave. He has told her this. "If something happens to Anna"—if not when said carefully—"I'm going to get into this War." Raising an eyebrow, he smiled. "I'll probably end up with a desk job. But if they'll have me, I'm going." Remembering, her eyes fill, and she sits back on her heels and with the sleeve of her sweater wipes the perspiration and tears from her face.

It's true that the tide has turned. Yesterday the Allies bombed industrial targets in a town called Brunswick, deep inside France. The Allies are winning. Everybody knows the War will soon be over. Farmers meeting on muddy, country roads trade shots of whiskey and hope through windows of pickup trucks: "This time next year, my boy will be home, helping me get the fields ready for cotton." Then, unable to voice the unthinkable, they add, "if the creek don't rise," or "if nothing don't happen." Women, boldly tempting the gods, lean from under hair dryers at Chic-les-Dolls Beauty Salon: "I didn't have the heart to put up a tree last Christmas. But this year we've already picked out the biggest one on the place!" So! It was agreed. Probably by September. Certainly no later than Christmas. All the sons and lovers and husbands—just boys, so young—will be coming home.

Young, until lately. Now they are calling up men as old as forty-five for active duty. And all over town, men even older are trying to get into the War. Some are fathers, desperately trying to follow their young sons—living, dead or missing-in-action sons—into battle. Everybody longs to play some part, however small, in the great and terrible—made unbelievably romantic by Hollywood—War.

Now a small gray spider, its filament of newly spun web invisible, appears before Grace's eyes. She moves her finger through the air above it, finds silken thread and deposits the wiggling spider on a hyacinth. By Christmas. Maybe by Thanksgiving, she tells herself, getting up, stretching.

In her kitchen, she fills the soup kettle with water, drops in cubes of beef (two red points, but never mind, she can get more from her washwoman), adds fresh vegetables, a can of tomatoes, garlic, a dollop of vinegar. She rolls oregano in her fingers, sniffs it, drops it in. Adds thyme. Rosemary. A witches' brew. Then she takes a bottle of red wine from the cupboard.

She has bathed and, dressing, got as far as her slip and stockings when Amelia calls. "Heard anything? From the hospital?"

"No."

"Call me."

"I'm fine."

And in the space between Amelia's question and her reassurance, she sees the evening, imagines it stretching before her—she, sitting with John while he eats, talking quietly about her garden and the good news from the European front, and John, comforted by the news and the soup, gradually relaxing, able to get through another night, another day.

After the briefest pause, "Good-bye," Amelia says.

Within the strong bonds of friendship between these two East Texas women there are carefully drawn boundaries that must not be breached. When Bucy left, Amelia had asked, "What would have happened if John had come to your door first? A blind date? Do you suppose—?"

Plucking a grocery list from the kitchen table and Amelia's questions from the air, "Let's go to the grocery store. Get our shopping done early," Grace had said quickly, strengthening a barrier, redrawing a line. But in the small neighborhood grocery (bread on one side of the aisle and canned goods on the other), Grace had imagined an eighteen-year-old gift, herself, in a white dress, running to answer the doorbell, opening the door to John—tall, blue-eyed, dark. And John, laughing, teasing, "I'm selling magazines, ma'am. Can I interest you in a McCall's? Redbook? In me?" And she, recognizing (a preternatural recognition) that here—in his arms, this!—is home, would have stepped through the doorway into John's arms. And in that single golden moment, she would have fallen in love with John, rather than slowly, sensibly (she tells herself this), through the long years.

"Grace, four cans of asparagus! I didn't think you liked canned asparagus," Amelia had exclaimed, calling her back. And she, astonished by her asparagus-filled basket, had laughed, "What could I be thinking of!"

John, that's what! Amelia had told herself. And since Grace's husband had gotten on a train and gone to New York with never a word to Grace or anybody else, Amelia kept her thoughts—always impossible, completely inappropriate—about her best friend's marriage to herself.

However, Amelia feels free to give certain kinds of advice: "Grace, you ought to get out more." She says this frequently.

But where in an East Texas town does an abandoned wife go? Grace wonders. Although she is not expected to climb upon a funeral pyre, she is psychologically shielded by the mystery of abandonment, the awfulness of it. For why would a man do that? Cold Springs asks. Just up and leave his wife! And one so pretty!

But Grace keeps her counsel about the whys of her husband's leaving, and John is there, next door. She is consoled by John's presence in the house next door, comforted by long summer evenings overhung by pewter-colored skies and John's telling of this or that trial and laughing at his own foibles, solaced by autumn's ripeness followed by the smell of pines drummed into the cold, crisp air by winter rains and the three of them before a bright fire in the Appleby dining room and, now, a new spring with the hyacinths and daffodils, the plum and peach trees once more in flower.

Listening to the evening news, Grace hears that guerrillas have killed four hundred Nazis near Mount Olympus in Greece and that the Germans in retaliation have shot 317 citizens at Messina. And our boys are still on the beach at Anzio, desperately fighting to gain a foothold. Oh, God, this horrible war. Let it be over soon, she prays.

When the soup is done, she goes outside to watch for John. She sits under the oak tree in the swing that John, under Anna's close direction, had hung for her. Clouds have rolled in, big cumulus clouds, the lowest one darkening, and it is this cloud, growing ever darker as it sweeps across the sky, that brings the wind. Thunder rumbles distantly. Over her head the huge branches of the oak lift and sway, propelling her back to her childhood. As a little girl, on just such a day, she would climb up into a tree as high as she dared, reveling in the wind that tossed the branches about.

She stands and, hands on her hips, gauges the height and the distance between the swaying branches. Could she climb this tree? Now? Maybe. Kicking off her shoes, she puts a foot on the swing, holds the chain by which it hangs, and then, grasping the highest limb she can reach, she sets her foot upon a strong, thick limb and pulls herself up. Turning to sit snugly against the trunk, she is immediately caught up in the revelous frenzy of the leaves.

Watching the branches tossing in wild abandon all around her, she thinks: If he were to see me now, what might he say? "Move over. I'm coming up there with you." Or holding up his arms: "Jump! Come on! I'll catch you."

She stays in the tree until she hears the phone, runs to answer it. John is calling from the hospital, his words so closed off, so choked by grief, she barely recognizes him. "The doctor says Anna will die tonight." His voice, sandpaper tearing, coming harshly from his throat: "Grace, could you—?"

"I'll come, John. I'll come right down," she says, but when she gets to the hospital, John has gone.

She sits outside Anna's door, knowing her friend is on her last journey. She listens to the staccato sounds of the crisply ticking clock, watches the sun dapple the brown linoleum floor. "Glory be to God for dappled things." She thinks of apples at the A&P and oranges. Lemons. Traps! Her mind veers away from Anna, trapped by death, on the other side of the shiny gray door.

Sometime later—who knows how long?—the nurse appears. Her look sweeps the waiting room. "Where is Mr. Appleby?"

"I don't know."

"Mr. Appleby's been drinking."

"Mr. Appleby's been suffering."

There is no compassion in the nurse's voice. "Mrs. Appleby is dead."

"I'll tell him."

Both houses are dark when she turns into her drive. She calls Amelia.

"Poor thing," Amelia says. "Two years is too long for anyone to suffer. How's John?"

"He's anesthetizing himself right now, or was. I'll take over some soup when he comes home."

When John has not returned by nine o'clock, she takes a tray—the soup, hot cornbread, fruit cocktail—to the gallery table. She eats slowly, listening for the sound of John's car in the drive.

When he has not come by eleven (Is he at the hospital? At the funeral home?), Grace puts on her gown and goes through the house turning out lights. Downstairs, a plaintive meow at the back door reminds her she has not fed Cal. She unhooks the back screen door, and although it is dark, some movement of shadows signals John's presence.

"John?"

"Here, Grace, I'm out here in the swing."

She slips on her robe and pads barefoot out to the backyard.

"Anna died," he says dully.

"I know."

"Sit down, Grace. Keep me company."

She sits by him. From time to time he starts the swing, and they move back and forth, or he reaches over and picks up a glass and drinks before carefully setting it down again.

"Anna," he says hoarsely. "She was never happy. I never made her happy."

"I don't know if you can make someone ..."

"Don't, Grace. Don't analyze this with fancy logic. It won't help."

He leans down, picks up his glass and holds it in both hands. "Sorry. But ... need to say this. Need to face it. My wife was never happy. She lived all those years and was never happy. When I married her, this little slip of a girl, eyes sad as a dove's call, `You'll be happy with me,' I told her. But, oh, Jesus!"

John is past tipsy. He is drunk. Tomorrow, will he remember what he is saying to her now? Will he be sorry? Will she?

"John."

"Hush. Hush, Miss Gillian. Oh, Miss Gillian. Hey, you know that poem? That crazy love song. You read it to me one day. Mr. T. S. Eliot wrote it, and God, I loved that poem! `I have heard the mermaids singing ... I do not think that they will sing to me.' Remember those lines? Well, Anna had. She had heard them. She knew they were out there, sunning on rocks far out in the sea. Listening to the songs of whales. And singing their mermaid songs. But they never sang to her. They only made her sad."

John. Always steady. Sound. And yet, this lovely poetic side, sending an unexpected note of pleasure down her spine.

He sips from his glass. She looks up at the sky. Not a star in it, not even the moon.

"Anna knew she was missing the fullness of life. Grace, old friend, do you know how sad that makes me? She went round, worried, trying so hard all the time to be happy."

"There were times when she seemed—"

"Seemed. Seemed!" His voice is scornful. He turns in the swing, grasps her shoulders. "Grace, you're happy. What makes you happy? Your silly garden? Your silly cat? Your silly turquoise house? Your silly ..."

"Husband?"

"Sorry, Grace. Sorry. No right. Have no right."

"What you just said. That's what's silly! My cat's not silly. Nor my garden. Nor my husband."

"Bucy. Well, I never understood how you and he ... Sorry. No business. But got to say one more thing. About Anna. I never made her happy. And, son of a bitch that I am, after a while, I stopped trying."

Feeling soft fur twining around her leg, she picks up her yellow cat. "John, it's misting. Let's go in. I'll feed you and Cal."

"No, no soup. Soup's for tomorrow. Come on," taking her hand, stumbling over a small wisteria bush, "I'll walk you home." He looks up at the sky. "Where are the blasted stars? Every blasted one of them has disappeared." Carefully holding his drink up, as if toasting the missing stars, he turns in a clumsy circle.

She takes his arm. "I think I'd better walk you home."

"No. No, Miss Gillian. Escort you to your kitchen steps."

At the foot of the steps he stumbles again, and she turns and brushes his face. Then he is in her arms and she in his, and nothing, not Anna's death, or old voices, not God himself can still the passion that sweeps them from the steps to her bed. He, made so by Anna's long illness, is as starved as she. Their lovemaking is fierce, passionate. Deeply satisfying. Afterwards, lying in his arms, tears run down her face.

"John." She sighs, a deep contented sigh. Words gather: I love you. I have always loved you.

But, "God," he says and is asleep.

Lying there, by his side, she wonders if some part of her has always known this would happen, that one day he would be her lover. Tomorrow she will tell him she loves him. She shifts her body so that it follows the contours of his and sleeps.

She wakes, is instantly awake, before daylight, and before she opens her eyes, smooths the empty pillow, she knows that he has gone.

When the sun rises, the house next door begins to stir. Cars come and go, doors open and close, muted voices sift into the bedroom. She does not see John. In the full light of day, in the full realization of his loss, she does not want to see him. It is too soon.

Grace

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 256 pages

- Publisher: Plume

- ISBN-10: 0452283396

- ISBN-13: 9780452283398