Excerpt

Excerpt

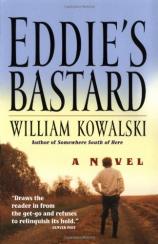

Eddie's Bastard

I Am Born; Grandpa Discovers Me, and

I Am Named; I Learn to Read; the Ghosts; I Encounter Annie Simpson

I arrived in this world the way most bastards do--by surprise. That's the only fact about myself that I knew at the beginning of my life. At the very beginning, of course, I knew nothing. Babies are born with minds as blank as brand-new notebooks, just waiting to be written in, and I was no exception. Later, as I grew older and learned things--as the pages of the notebook, so to speak, became filled up--I began to make certain connections, and thus I discovered that among children I was unusual. Where others had a mother, I had none; father, same; birth certificate, none; name, unknown. And as soon as I was old enough to understand that babies didn't just appear from midair, I understood that my arrival was not just a mystery to myself. It was a strange occurrence to everyone who knew me.

Nobody seemed to know where I was born, or exactly when, or to whom. Nor did anyone know where I was conceived. How, of course, was obvious. Contrary to my earliest notions, babies don't just appear, though in my case this seemed entirely possible. Somewhere, sometime, my father had sex with my mother, and here I am.

In the space for mother, then, there is nothing but a blank.

I know who my father is--or was, rather. He was Eddie Mann, Lieutenant, USAF (dec.). The dec. stands for deceased. At one time, I had my own suspicions of who my mother was, and so did everyone else who knew me. They were all vague and unprovable, however, and suspicions are best left to the tabloids, which I read sometimes while waiting in line at the supermarket.

I confess to a weakness for tabloids; they stimulate my imagination, get me to thinking that perhaps the impossible is not so far removed as we might think. My favorite articles are the ones about Bat Boy, half human child and half bat, which someone claims to have found in a cave somewhere in the South. I sympathize with Bat Boy, even though I don't believe in him. I imagine myself having lengthy conversations with him, teaching him how to play baseball, being his friend. Like me, his appearance was unexpected, and nobody seems to know quite what to do with him.

My imagination--the part of my mind that allows me to believe in Bat Boy--also stretches back to the time before I was born, and before. I see my mother, a pregnant young girl, panicked but with a strong conscience, and some desire to see me succeed in life. She gives birth to me in secret somewhere: a train station, a taxi, under a tree in the middle of the forest. Then, after I'm born, she--a princess, a faerie queen, Amelia Earhart--deposits me on the back steps of the ancestral Mann home in Mannville, New York, where my father had been born and raised--as had his father, and his father before him. This is where my imagination is relieved of duty and the facts take over. This part of the story really happened.

It was the third of August, 1970. My grandfather, the herbalist and failed entrepreneur Thomas Mann Junior (no relation to the writer of the same name), who lived alone and abandoned in the farmhouse, found me there. Like some character in a Dickens novel, I'd been wrapped in a blanket and placed inside a picnic basket. Many years later, I was to discover that Grandpa had saved the picnic basket, a deed for which I've always been profoundly grateful. For years, it was my greatest treasure. It was the one thing in the world I was sure my mother had touched.

It was just after dawn, and the day was Grandpa's birthday. Grandpa celebrated his birthday the same way he celebrated every other day: he drank whiskey, sitting alone at the scarred and ancient kitchen table. He drank whiskey in the morning, drank it for his lunch, drank before dinner, and drank after dinner. Sometimes he didn't bother to eat dinner at all. Eating sobered him up, and that was unpleasant; he preferred to be drunk. But today there was something unusual going on, something to break the monotony of his drunkenness. It was my crying. Grandpa heard it dimly, out of the corner of his ear, as it were. It sounded familiar. It was a noise he'd heard before, but he couldn't quite place it.

"Chickens," he said to himself. I know he said this because laterhe was to tell me the whole story over and over again. There were no chickens left on our farm anymore and hadn't been for years, but sometimes he forgot this. Grandpa, when drunk, remembered better days, when chickens on the farm meant prosperity and things going right. In those days the farm was still operating, the crops were still growing, my father was still just a baby, the Ostriches had yet to wreak their havoc upon our future, and chickens roamed free. In Grandpa's sodden and inebriated mind, chickens meant hope, and they had to be protected.

So he interrupted his drinking. He stepped out the kitchen door to see if there were foxes in the chicken coop, which, though long de-serted, still stood. Instead of foxes, however, he found me.

Years afterward, Grandpa told me he'd nearly stepped on me as he came out the door. The sudden roar of a military jet overhead had caused him to stop his foot in midair as he looked up. It saved my life.

"Thank God for that jet," Grandpa said, "or I would have squashed you like the little bug you were."

It was the year the polluted Cuyahoga River burst into flames and burned for three days. The nation, divided by Vietnam, was united in its horror at the alchemic spectacle of flaming water; the beginning of my life coincided with a growing awareness that the world was polluted and dying, and that it was our own fault. I've always considered that event an omen of my birth.

Eddie's Bastard

- paperback: 384 pages

- Publisher: Harper Perennial

- ISBN-10: 0061098256

- ISBN-13: 9780061098253