Excerpt

Excerpt

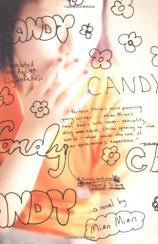

Candy

A

Why did my father always have to push me in front of the Mona Lisa? And why did he always make me listen to classical music? I suppose it was just my fate, for want of a better word. I was twenty-seven years old before I finally got the courage to ask my father these questions-up until then, I couldn't even bring myself to utter the woman's name, I was so terrified of her

My father answered that Chopin was good music. So when I was bawling my head off, he would shut me in a room all by myself and have me listen to Chopin. In those days none of our neighbors had a record player or a television the way we did. What's more, many of them were forced to subsist on the vegetable scraps they scrounged at the market, since meat, cloth, oil, and other basics were still being rationed. My father thought that as a member of the only "intellectual," or educated, family in our entire apartment building, I should feel fortunate

Father said that it had never occurred to him that I might be afraid of that print hanging on our wall. Why didn't I just look at the world map that was hanging right next to it? Or the map of China? Or my own drawings? Why did I have to look at that picture? At length he asked, Anyway, why were you so afraid of her?

Many other people have asked me this very question, and each time someone asks, I feel that much less terrified. Still, it's a question I can't answer. Just as I can't explain why, from the time I was a very small child and barely able to talk, my father would have chosen to deal with my crying the way he did

I have never actually taken a good close look at that woman (I'm far too afraid of her to attempt that). Nonetheless, my most powerful childhood memories are of her portrait

As I grew older, certain ideas became fixed in my mind. Her eyes were like a car crash at the moment of impact; her nose was an order issuing from the darkness, like a ramrod-straight ladder; the corners of her mouth were cataclysmic whirlpools. She seemed to have no bones except for her brow bones, and those bald brows were an ever-present mockery. Her clothing was like an umbrella so massive that it threatened to steal me away. And then there were her cheeks and fingers. There was no denying that they resembled more than anything the decaying pieces of a corpse

She was a dangerous woman. And I was often in this dangerous presence. I had very few fears, but she terrified me. In middle school history class, I was once startled to look up and find myself face-to-face with a slide projection of this painting. My throat tightened, and I cried out in shock. My teacher reacted by concluding that I was a bad student and making me stand up as punishment

Then he took me to see the assistant principal, who gave me a stern lecture. At one point they went so far as to accuse me of reading "pornography," like the then-popular underground book The Heart of a Young Girl.

That was the beginning of my hatred for the man who had painted her. And I started to despise as well all those who called themselves "intellectuals." My hatred had a kind of purity about it-I would open my heart and feel a convulsive anger pulsing in my blood. I named this sensation "loathing."

My unalloyed fear of this painting stripped away any sense of closeness I might have felt toward my parents. And it convinced me, all too soon, that the world was unknowable and incomprehensible. Later I found the strength to deal with my fear. I found it in the moon and in the moonlight. Sometimes it was in rays of light that resembled moonlight, and sometimes I saw it in eyes or lips that were like moonlight. At other times still it was in the moonlight of a man's back

B

When it rains I often think of Lingzi. She once told me about a poem that went: "Rain falling in the spring, / Is heaven and earth making love." These lines were a puzzle to us, but Lingzi and I spent a lot of time trying to unravel various problems. We might be trying to figure out germs, or the fear of heights, or even a phrase like "Love is a fantasy you have while smoking your third cigarette."

Lingzi was my high school desk mate, and she had a face like a white sheet of paper. Her pallor was an attitude, a sort of trance. Those days are still fresh in my mind. I was a melancholy girl who loved to eat chocolate and did poorly in school. I collected candy wrappers, and I would use these, along with boxes that had once contained vials of medicine, to make sunglasses

Soon after the beginning of our second year of high school, Lingzi's hair started to look uneven, with a short clump here, a longer hank there. There were often scratch marks on her face

Lingzi had always been extremely quiet, but now her serenity had become strange. She told me she was sure that one of the boys in our class was watching her. She said he gave her steamy looks- steamy was the word she used, and I remember exactly how she said it. She was constantly being encircled by his gaze, she said. It made her think all kinds of unwholesome, selfish thoughts. She insisted that it was absolutely out of the question for her to let anything distract her from her studies. Lingzi believed that this boy was watching her because she was pretty. This filled her with feelings of shame. Since being pretty was the problem, she had decided to make herself ugly, convinced that this would set her back on the right path. She was sure that if she were ugly, then no one would look at her anymore; and if nobody was looking at her, then she could concentrate on her studies. Lingzi said she had to study hard, since, as all of us knew, the only guarantee of a bright future was to gain admission to a top university

Throughout the term, Lingzi continued to alter her appearance in all kinds of bizarre ways. People quit speaking to her. In the end most of our classmates avoided her altogether

As for me, I didn't think that Lingzi had been that pretty to begin with. I felt that I understood her-she was simply too high-strung. Our school was a "key school," and it was fairly common for a student at a school like ours to have a sudden nervous breakdown. Anyway, it wasn't clear to me how I could help Lingzi. She seemed so calm and imperturbable

Then one day Lingzi didn't come to school. And from then on, her seat remained empty. The rumor was that she had violent tendencies. Her parents had had to tie her up with rope and take her to a mental hospital

Everyone started saying that Lingzi had "gone crazy." I started eating chocolate with a vengeance, and that was the beginning of my bad habit of bingeing on chocolate whenever I'm anxious or upset. Even today, eleven years later, I haven't been able to break this habit, with the result that I have a very serious blood sugar problem

I sneaked into the hospital to see her. One Saturday afternoon, wearing a red waterproof sweat suit, I slipped in through the chain-link fence of the mental hospital. In truth, I'm sure I could have used the main entrance. Although it was winter, I brought Lingzi her favorite Baby-Doll brand ice cream, along with some preserved olives and salty dried plums. I sat compulsively eating my chocolates while she ate her ice cream and sweet olives. All of the other patients on the ward were adults. I did most of the talking, and whenever I finished saying something, no matter what the subject was, Lingzi would laugh. Lingzi had a clear, musical laugh, just like bells ringing. But on this day her laughter simply struck me as weird

What did Lingzi talk about? She kept repeating the same thing over and over: The drugs they give you in this hospital make you fat. Really, really fat

Sometime later I heard that Lingzi had left the hospital. Her parents made a series of pleas to the school, asking the teachers to inform everyone that Lingzi was not being allowed any visitors. One rainy afternoon, the news of Lingzi's death reached our school. People said that her parents had gone out one day, and a boy had taken advantage of their absence. He had brought Lingzi a bouquet of fresh flowers. This was 1986, and there were only two flower stands in all of Shanghai, both newly opened. That night, Lingzi slashed her wrists in the bathroom of her family's apartment. People said that she died standing

This terrible event hastened my deterioration into a "problem child."

I quit trusting anything that anyone told me. Aside from the food that I put into my mouth, there was nothing I believed in. I had lost faith in everything. I was only sixteen, but my life was over. Fucking over

Strange days overtook me, and I grew idle. I let myself go, feeling that I had more time on my hands than I knew what to do with. Indolence made my voice increasingly gravelly. I started to explore my body, either in front of the mirror or at my desk. I had no desire to understand it-I only wanted to experience it

Facing the mirror and looking at myself, I saw my own desire in all its unfamiliarity. When I secretly pressed my sex up against the cold corner of my desk, I sometimes felt a pleasurable spasm. Just as it had been the first time, my early experiences of this "joy" were often beyond my control

This was the beginning of my wasted youth. After that winter, Lingzi's lilting laughter would constantly trail behind me, pursuing me as I fled headlong into a boundless darkness.

Candy

- paperback: 304 pages

- Publisher: Back Bay Books

- ISBN-10: 0316563560

- ISBN-13: 9780316563567