Interview: May 8, 2019

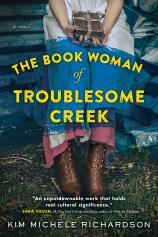

A young outcast braves the hardships of Kentucky’s Great Depression and brings truly magical objects to her people --- books --- in THE BOOK WOMAN OF TROUBLESOME CREEK, Kim Michele Richardson's new novel inspired by the brave women of the Pack Horse Library Project. In this interview, conducted by Bookreporter.com reviewer Megan Elliott, Richardson talks about her inspiration for writing a book that features a pack horse librarian as the protagonist, the incredible amount of research she did for the novel (which began nearly five years ago), her remarkable ability to write in dialect without coming off as inauthentic or clichéd, and what she hopes readers will take away from her latest work of historical fiction.

The Book Report Network: Your latest novel is a powerful story rooted in historical fact. As a reader, I initially assumed that you had invented the Blue People of Kentucky since they seem so extraordinary, but Cussy Mary Carter and her family are based on real people who suffered from a little-known blood disorder called methemoglobinemia. Can you talk about how you learned about the Blue Fugates and why you decided to place that story at the heart of your novel?

Kim Michele Richardson: I learned of the Fugates long ago and became endeared with them after I learned how unfairly they were treated. I wanted to give them a voice they’d long been denied due to ignorance, stereotyping and misunderstanding of their medical condition.

TBRN: THE BOOK WOMAN OF TROUBLESOME CREEK also draws on the history of the pack horse librarians. These were people --- mostly women --- who delivered reading material to some of the most remote places in the Appalachian Mountains as part of a WPA program during the Great Depression. What inspired you to write a book that features one of those librarians as the protagonist?

KMR: For 80 years, these brave, heroic Kentucky pack horse librarians were ignored with the exception of several amazing children’s books --- the women's historic legacy but a small footnote in history. Their courage and dedication for spreading literacy to the poorest pocket of the United States --- the hills of eastern Kentucky --- and during its most violent era deserved more in literary history. I felt it would be a privilege to tell their story. There’s not a day that goes by when I don’t feel a tremendous honor for the opportunity to finally introduce these fierce, female pack horse librarians, and the blue people from my home state of Kentucky.

TBRN: Your novel opens with a scene that some people might find shocking (and to which you circle back towards the book’s end). Did you worry that beginning with such an arresting moment might be too disturbing for some readers?

KMR: There were three or four drafts of different opening scenes, and in the end my publisher and I strongly felt that this one was the most authentic and honest, and set the tone for this book. Anything else would feel dishonest. Most writers I know compulsively worry and fret over what readers may or may not like. But in the end, that fear arrests the story. And like a dear writer friend told me long ago, writing with the tiniest of fear is like spilling a drop of raw sewage into a gallon of fresh spring water. One drop, the smallest speck, destroys the whole jug.

TBRN: You did an incredible amount of research for this book. What was that process like?

KMR: It began nearly five years ago when I started collecting everything I could find on the pack horse librarians --- poring over archives, old newspapers, pictures, the history, etc. I spent countless hours on Roosevelt’s New Deal and WPA programs, and also conducted many interviews. Thousands of hours were spent exploring everything from fauna to flora to folklore to food, and longtime traditions indigenous to Appalachia. Other research took me to coal-mining towns and their history, visiting doctors, speaking with a hematologist to learn about congenital methemoglobinemia, and exploring fire tower lookouts and their history. And last, during this remarkable and sometimes crazy journey of living full time in Appalachia for research, I clumsily fell off a mountain and received seven breaks to my arm, and my husband caught Lyme’s disease. All part and parcel in the name of research.

TBRN: Your book draws strongly on the historical record, but it is still fiction. As a writer, how do you balance staying true to the realities of the past with crafting a compelling story?

KMR: Staying true to the past means weaving in authentic facts with a compelling storyline and a colorful cast of characters. It often comes at the cost of many drafts and the talented eye of my fine editor.

TBRN: You live in Kentucky, and all of your novels are set in that state. One thing I particularly enjoyed about THE BOOK WOMAN OF TROUBLESOME CREEK was how deeply rooted it was in a particular place. Why do you think those Kentucky settings provide such fertile ground for your writing?

KMR: Kentuckians are very complex and proud people. The land is brutal and beautiful, full of mystery, folklore, tradition, secrets and very rich history to draw on.

TBRN: The community you describe in your novel is isolated and impoverished. What has changed --- and what hasn’t --- for the people living in Appalachia since the 1930s?

KMR: Sadly, not much has changed since President Johnson squatted on Tom Fletcher’s porch in Inez, Kentucky, 55 years ago last month to declare his War on Poverty. It could even be described as worse. Some of these people live without clean drinking water and have been living in constant crisis for years.

TBRN: Cussy Mary --- aka Bluet --- has had a hard life. She is a woman, she is poor, and she is discriminated against because of her color. She experiences moments of great sadness and trauma, but she doesn’t give in to self-pity or total despair. How is she able to maintain hope and a sense of purpose in the face of her many troubles?

KMR: Cussy Mary is a fierce, determined woman like the other courageous pack horse librarians of the Depression who battled everything from inclement weather, mistrust, treacherous landscapes and extreme poverty, and again, doing it all in Kentucky’s most violent era --- the bloody coal mine wars. These dedicated book women were grateful to have the opportunity to spread literacy and knew the importance of helping their own people through this very important pioneer library project.

TBRN: You don’t shy away from describing how difficult life is for Cussy Mary and the other hill people, and there are a number of bleak moments in this novel. But there are also many occasions of kindness and grace. Was it challenging to marry the story of the hardscrabble lives you describe with those more hopeful moments?

KMR: Yes, it was challenging and not an easy journey, but nor was that era, so it became important for me to present it honestly. Though many are starving and dying of the pellagra and coal-related diseases, the reading material Cussy Mary brings to the hillfolk are food for the soul --- life-changing and a testament to how the written word can be powerful enough to change lives.

TBRN: Cussy Mary is the book’s protagonist, but there’s also a vivid cast of secondary characters, like R.C. Cole, the fire watchman, and Queenie, the African-American pack horse librarian. Do you feel especially close to one of those characters, or who was a favorite to write?

KMR: They are all so dear: Young, innocent Angeline, fire-tower lookout RC, ol’ weak-eyed Loretta --- there’s too many to choose just one. We have Junia, Cussy Mary’s protector. Surprisingly, I’m finding so many are endeared to that ol’ feisty mule, and I receive many funny and sweet letters about her.

TBRN: One of the more intriguing characters to me was Doc. He has a complicated relationship with Bluet that at times seems exploitative. Can you talk about how you created that character, his motivations for helping Bluet, and how he evolves over the course of the book.

KMR: Doc is a complicated man, and at first we see that he is motivated to help the Blues only to advance his standing in the medical community. Then we see a different kinship slowly unfold as he becomes a protector and works to humanize the precious Blues.

TBRN: Cussy Mary and many others in your book speak in a strong and distinct Appalachian dialect. Writing in dialect can be difficult, and in the hands of less skilled authors, it may come off as inauthentic or clichéd. How did you go about incorporating local idioms and speech patterns into your writing without falling into those traps?

KMR: I’m a Kentuckian first, so I know that in different regions of my home state there will be different beats and song in the native language. I’m also able to live in that landscape and spend time with native Appalachians who have taught me the lyrics and language of their people and ancestors.

I hear different dialect and speech patterns every day, and in all my travels in Kentucky and beyond. But at some point you do try to keep in mind that the rest of the world doesn’t. Example: I have a nephew whose words I can barely understand because he comes from a different pocket of Kentucky. Still, there’s a balance, and you can’t strip the music, the lyrics that honestly reflect the people. So when I hear someone comment on any book that the dialect distracted them, I perk because itis different, and I want to learn and be fully immersed in that different world to enrich my knowledge.

TBRN: THE BOOK WOMAN OF TROUBLESOME CREEK is a historical novel, but many of the themes --- such as the pernicious effects of racism and prejudice, and the unfortunate legacy of generational poverty --- continue to resonate today. What do you hope readers will take away from the book?

KMR: That poverty and marginalization are not so much economics or politics or societal issues as much as human issues that are best grappled with by reaching deep into the lives of those suffering them. Texas librarian Kelly Moore summed it up best in her recent review of THE BOOK WOMAN OF TROUBLESOME CREEK: "As I turned the last page I found myself wanting to be more kind, compassionate, tolerant and charitable as I began a new year."

TBRN: Your novel speaks eloquently about the power that reading and books have to transform people’s lives. What books and authors have impacted you the most over the years?

KMR: E.B. White's CHARLOTTE’S WEB is a masterpiece that tapped into my love for nature and animals. And every time I read it, I learned something new. It has the wonderful Hitchcockian first line: "Where is papa going with that axe?" and is infused with magical verses of dewy spider webs, "Some Pig" miracles and unconditional friendship. Some Book!

There are so many talented writers out there to pick from, it makes the choice difficult. But Harriette Simpson Arnow, John Fox, Jr., Gwyn Hyman Rubio and Walter Tevis are some of my longtime favorite Kentucky novelists who wrote unforgettable masterpieces. Each one brings the pages to life with rich, evocative landscapes, beautifully told stories and highly skilled prose.

TBRN: What are you working on now, and when might readers expect to see it?

KMR: I’m into research and working on something that’s too early to reveal, but I can say that it is again set in Kentucky and will have an intriguing and very colorful cast of characters.