Excerpt

Excerpt

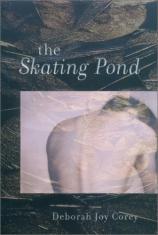

The Skating Pond

My grandfather died at sea while he and Father were lobstering. It was 1954, the year I was born, and Hurricane Edna was beginning to whip up the seas. A white wave took Grandfather from the stern of the boat. After that, Father hated the sea. He said it was an unpredictable force with the personality of a shark, swallowing whatever was in front of it whether it was hungry or not. Apparently, Grandfather had been swept away in a matter of seconds. Father never spoke of him again. He made Grandfather's bedroom into his painting room, then painted a multitude of empty and abandoned fishing boats. When I was five, I suggested he try painting something different and his mood turned dark. Years later I would see a painting by the Maine painter John Marin, in which the sun was black on white canvas, its contrast so intense with the white that it gave the effect of burning through the paper. My father's darkness could burn through me, too, making me as insignificant as a pile of ashes.

If skating was my mother's toehold on youth, then painting was Father's toehold on death. I believe he was trying to resurrect his father by painting those fishing boats. Sometimes, if he finished a particularly tattered boat, one that looked as if it had gone to the bottom of the sea and back, he became almost giddy. He idealized his world on the flat plane of a canvas, and for a time that seemed to give him the control he so desired.

Beside my plate at the supper table was a pencil sketch. It was on a three-by-five piece of white paper and in the picture I was glancing downward with my thin lips in a satisfied curve. Father must have made some mistake, for the portrait was neither me nor not me. It was somewhere in between, like the photograph of a baby in a womb, bland but somehow individual. "What about the boy on the rocky shore?" I asked.

He's finished," Father said, sitting down at his place. Mother was sprinkling her toast with cinnamon and sugar and the kitchen smelled of Christmas. She licked the corners of her mouth, savoring the sweet specks. "Peter," she said, "when are you going to do me skating?"

Father's face lost its expression. He was not partial to Mother's skating. Once, while they argued about her preoccupation with the pond, he said, "People see it as decadence, Doreen. You have a home and a family. You should be here." He was lying on the kitchen couch and dust particles were rolling in the white rays of sunlight near his wool socks. He was reading a tattered book.

Mother was sitting at the table looking at pictures of Peggy Fleming, who had just won a gold medal at the Olympics. "What?" she said.

Father repeated himself and Mother slapped her magazine shut, staring at him. Father looked at her for a moment, then threw his book, which only grazed her and landed beside my feet, where I stood looking over her shoulder. Mother got up and marched off while I picked the book up and looked inside. The corner was turned down on a center page and I read, "And had you watched Ahab's face that night, you would have thought that in him also two different things were warring."

After supper, I ripped the sketch of myself in two and placed it between the pages of my prayer book. It was windy and the windows rattled. Frost had made shapes like faces on the pane. I put my fingers on the smallest face to melt eyes, then pulled them back, wet and cold. I imagined the distant breakers where salty seawater rose and turned white and waves twisted and crashed and rolled against the islands. Sometimes when we watched the wild sea, Father said she was having a temper tantrum and all anyone could do was wait until it was over. With these words he sounded helpless, as helpless as a man watching a loved one being swallowed by a wave.

The face that Father sketched was of an older me. Of all his qualities, intuition was the strongest. He could look at something and know what time was capable of doing to it. When he painted any person, you could see how well he understood their essential framework, and on their skeleton he hung their future: saggy expressions, slouching shoulders, and protruding bellies. Perhaps that is why people asked for paintings of boats instead of portraits of themselves.

On Saturday night of that week, we all went to the pond. Father took his sketch pad and Mother and I took our skates. There was a line of lightbulbs on wire strung across the pond and the lights were lit and swaying. The night was deep navy blue everywhere except for the rink where the lights and wind made a yellow moving glow over the ice. A large speaker on top of the skating shed played Patsy Cline's "Crazy."

Mother was wearing white tights and a white skating skirt. She had sewn silver sequins to the hem and it sparkled when she moved. The shed was full of people, and all types and sizes of boots were piled and spilling from under the benches. Father helped me tighten my skates while Mother raced to get outside. "Does she ever wait for you?" he said in an accusing way. I shrugged, chewing the end of my mitten. Father's black whiskers poked from his face. He asked again, but I said nothing.

When we stepped outside, Mother was up near the boys playing hockey. She was doing backward crossovers in a huge private circle. Julie Ann was there and so I skated off with her, picks first, while Father sat on the new snow at the edge of the pond and began to sketch. Occasionally, he looked up to find Mother or me, but mostly he just made little thrusting movements with his pencil and greeted familiar faces as they skated by. Once, when Julie Ann and I were going by, she yelled, "What are you drawing, Mr. Johnson?"

He looked up and smiled. "A boat."

I was taken aback because I pictured a skating scene with recognizable figures. "Elizabeth," he called out, "don't go near the edges of the pond. It may not be frozen."

Julie Ann looked at me and lifted one eyebrow. A cold snap had left the temperature below freezing for days. I ignored her expression and skated off toward Mother. Julie Ann followed and there seemed to a be a small apology in her enthusiasm to keep up.

I didn't want to get too close to Mother fearing that she'd correct me on my T pushoffs. Julie Ann and I made a spot for ourselves in the center of the pond where the ice was white and it was hard to believe that somewhere under us water flowed and lilies waited to bloom again. There were a lot of girls with their boyfriends. They skated around the edge hand in hand. "Do you think they kiss?" Julie Ann said pointing to a couple with matching cableknit sweaters.

"I don't know," I said, and Julie Ann slipped her mitten in mine as if somewhere in the quietest parts of ourselves, we were making a similar silent wish.

I don't think Father was looking when Mother got hit with the puck, but I heard something. I believe it was the cracking of her forehead. They said she was spinning so fast that the sequins on her skirt looked like neon and that when the puck struck her, all her bones seemed to dissolve and she fell like cloth to the ice. The first thing I saw was Father running across the pond and the skaters moving with him like lemmings racing for the sea. Someone scratched the needle across the record and the speaker blared out a ripping sound. The night was just cold weather touching us with the sound of lightbulbs swinging in the wind and the scraping of blades on the ice. Julie Ann and I were still holding hands and she began to pull me toward Mother. Instantly, my legs and arms swelled with weight and something that weighed like a heavy black stone grew in my chest.

The puck had hit Mother between her eyes. One side of her face was pressed hard against the ice. A slender white bone jutted out between her eyebrows and dark blood gushed from the split it made. Father lifted Mother up. The violet-colored blood poured from the cut and her nose in a steady stream to the ice. I stood in the circle of skaters away from them. There was a lot of staring and whispering. The lights made swinging shadows across Mother's face and there was so much blood that I thought it must be seeping up from the pond. The sequins lay like a silver snake on her legs and one of her thigh muscles was pulsating. A young boy with a navy face mask began to cry. Julie Ann looked at me and I smiled, my body somehow separate from my feelings.

When the sled arrived, Father put his hand out and held everyone at bay. "Doreen," he said, "can you hear me?"

Mother's eyes stayed closed but her mouth fell open in an O, the slack-jaw hollow O of opaque. Father wiped the blood away from her lips and underneath they were the softest color of pink, like the tongue of an infant. A breath of white escaped her and rose up to Father. For a moment, he closed his eyes and it looked as if they were both sleeping. When he opened them, the creases in his face had grown deeper like ruts in a heavily traveled road. He touched the swelling over her eyes, which made her forehead sway like water. "I'll put her on," he said.

We all watched, waiting for some sign of life to come from Mother and when she revealed nothing, we became a parade following the sled across the ice.

Back in the shed, everyone gathered to wait for the ambulance to come from Blue Hill. Father never took his eyes off Mother. He held his brown woolen glove to her nose and head to stop the bleeding and it was wet and dripping like a sponge. Blades banged gently on the wooden floor making a dull sound that beat at the black stone inside of me. Everyone was huddled around the sled that held Mother and once in a while someone would touch me on the back to comfort me. At the time, Mother didn't look enough like herself for me to cry, but I did wish hard for Father to kiss her.

"Could you clear the shed?" Father said. Mother had not moved and the curtness in his voice probably came from the worry that she might not. He wrapped his hand around her baby finger that stood in the air and squeezed it. Whispers carried the skaters in a slow exit and I was moved with them back out to the pond.

Mother was in Blue Hill Hospital for one night, then transferred to St. Joseph's Hospital in Bangor, where she stayed for three and a half weeks. When we brought her home, her nose was flat and her once almond-shaped eyes seemed to have been traded in for wider ones. Her forehead was sunken like the dip over a grave and her face was still swollen and blue. Much later in life, I would see pictures of children who suffered from fetal alcohol syndrome and be reminded of Mother. When Mother wandered about the house, I stood out of her way as if she were a stranger.

"Elizabeth," she said. "Are you afraid of me now?" She was unscrewing the mirror from her dresser and I was sitting on the bed, watching my reflection. "No," I said, not really sure if I was or not. My long and wild hair blazed black in the sunlight, but my lips looked wispy and pale like the cirrus clouds that come before a warm front.

"Don't be afraid," she said. "Nothing has changed."

I wanted to cry, but instead I turned to the window. It was a calm cold day and a row of icicles hung there. They were lavender in the bright light, the very lavender of summer lupines and there were a thousand tiny bubbles trapped in their frozen surface. I looked back. "Is your face going to get better?"

Mother rested the round mirror up against her thighs and it made a circle of dust on her jeans. "Don't expect anything," she said.

I wanted to say that I wasn't expecting anything, that it didn't matter what she looked like, but she had already lifted the mirror and was carrying it out of the room.

She took all the mirrors down and piled them like old photographs in the cubbyhole under the stairs. "Why are you doing this?" Father asked when he heard one of the mirrors crack. Mother stopped and looked up at him. You could say she was trying to stare him down, but her eyes were not strong enough to focus. They wavered back and forth––shivering.

Father shifted his weight. "Doreen." He sighed. "How am I going to shave?"

She lifted the stack of mirrors and pulled out a small one that used to hang in my room. I had made it at summer camp by gluing small seashells and colored glass to the rim. They had been washed by the ocean and they were smooth and warm to touch. As she handed it to Father, a periwinkle shell fell off and lay between them. Neither of them reached for the shell so I dipped down quickly and picked it up, white grains of sand dropping like salt on the dark floor.

Father put the mirror under his arm and walked to his room.

Mother looked up at me. "Do you want one, too?"

I studied the inside of the periwinkle shell. It was mauve like the still-bruised parts of Mother's face. "Not now," I said.

Excerpted from The Skating Pond © Copyright 2003 by Deborah Joy Corey. Reprinted with permission by Berkley, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc. All rights reserved.

The Skating Pond

- hardcover: 256 pages

- Publisher: Berkley Hardcover

- ISBN-10: 0425188353

- ISBN-13: 9780425188354