Reading Group Guide

Discussion Questions

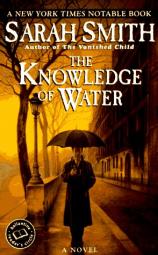

The Knowledge of Water

1. Why do you think the author chose the Great Paris Flood of 1910 as the historical reference point for The Knowledge of Water? What important part does water play in this story?

2. We recently suffered though a disastrous series of floods here in the United States. Keeping the video and photographic images from those floods in mind, how do you think Paris changed after the great flood of 1910?

3. One of the underlying themes of this book is the mystery of identity--determining what is real and what is forgery. Which do you think is most real with Perdita--love, art, or both? And who is the deceptive artist? Do you believe that people create forgeries of themselves and their relationships?

4. Characters in The Knowledge of Water have some secret they can't tell. They don't have the words; they don't know what it is or are ashamed to tell it; Leonard can neither write nor speak clearly. What's the relationship between learning to speak, finding the right words, and solving a crime? Can not speaking, or speaking what is not factually true, ever be as true as finding the right words and saying them?

5. Family histories connect with identity in The Knowledge of Water. For example, Reisden says he is Dotty's cousin. To what extent can one use or create family to create one's self? How can families hurt or help one's search for identity?

6. Another major theme in The Knowledge of Water is the notion that women can't have it all--love, family, and a profession. Perdita says, "the best possible way of life" would be "to have love and music both," and her friend Florrie tells her, "The best possible way of life--isn't possible" (p. 38). Who do you think is right? Can women have it all--and is that what women want?

7. "I accept my difficulties," Armand Inslay-Hochstein says about the swindle he perpetrated, "and [my son] will have Mallais" (p. 453). Madame Mallais asks her husband, "Was it really worth it, for them paintings?" (p. 308). Do you think their crime was worth it? Of the various solutions to the Mallaises' problem given at the end of the book, which one do you prefer? How would you solve the problem?

8. At the end of the book, George Vittal declares, "I have come to free you from the tyranny of Art!" (p. 463). Mallais believes, "Art's to fail at ... it changes you ... makes anything possible; and then you ... try the impossible ..." (p. 436). What is art? What's the difference between art and forgery?

9. Perdita thinks, "Even if you can't live up to your destiny, you can at least have one" (p. 456). What do you think she means by this?

10. Perdita accuses herself of wanting to be married rather than loving Reisden; he accuses himself of wanting companionship, and sex, but not truly wanting her. At the end of the book, we can foresee that their love won't run smoothly. Is this a friendship that has turned awkward? Why do you think the author chose to make the question of their love so ambiguous?

11. Leonard says, "The more trouble a man has in loving [a woman], the more worthy he is of her" (p. 48). Leonard is the romantic in an anti-romance, a book that's been accused of having a deeply pessimistic view of love. Is he right? Is there a value in sacrificing for love, even love of the wrong kind?

12. Madame Mallais tells Perdita to "take yourself back" (p. 245). Did she ever give herself away?

13. "All love is selfish," says Milly Xico, the cynical French ex-writer; love, she says, is a male want, a trick men play on women--and on themselves (p. 57). Why do Reisden and Perdita fall in love? In what ways is that love selfish? Can one be in love for selfish reasons?

14. Reisden criticizes Perdita when she defends the forged reviews and Madame Mallais's forgery (pp. 363Ü365), but himself sees the value of forgery (pp. 236, 310). Does forgery have a value--sentimental, artistic, or monetary? Is art, as Mark Jones suggests in the epigraph, "mainly fashioned to be appreciated and acquired by others"? Can forgery be an "art" of deception?

15. In the classic mystery, there are three roles: victim, murderer, and detective. There is a crime, a process of discovery, and a solution. The Knowledge of Water has all these, but is it really a mystery? 16. Some readers think that the book should end with Perdita's decision to play the piano and Reisden's to let her tour (pp. 455Ü456). But it ends nine pages later, after Milly's description of the flood ("On this night we have become history") and Milly's decision to write again, when she throws her own art into the Seine. Why do you think the author did this? (The author has said she doesn't completely know why this ending is the right one but feels strongly that it is.) 17. Some reviewers have said the book has too many story lines and characters. Do you think it loses impact because of them? 18. Secondary characters add to the impact and tone of a book. How do characters like Dotty and Barry Bullard change the tone of The Knowledge of Water? 19. Writing by actual people appears throughout The Knowledge of Water, and characters are based on real people. (Among the well-known substitutions are Esther Cohen for Gertrude Stein; Milly and Henry for Colette and Willy; George Vittal for Guillaume Apollinaire; and Gastedon for Picasso.) But everything is changed, renamed, and misquoted. Does this mean that all historical fiction is essentially a forgery, a collage, or an "impression" (p. 465)? Is this a bad thing?

The Knowledge of Water

- Publication Date: September 8, 1997

- Paperback: 469 pages

- Publisher: Ballantine Books

- ISBN-10: 0345409639

- ISBN-13: 9780345409638