Excerpt

Excerpt

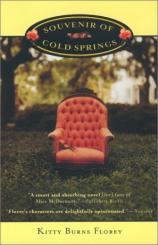

Souvenir of Cold Springs

MARGARET

1987

Anywhere, Margaret thought. Chicago, Minneapolis, Denver, but preferably someplace warm. Honolulu, Acapulco, Saint-Tropez. On the subway, she recited the names of cities to herself, a rosary of places that weren't Boston. Palermo, Pamplona, San Juan. Miami Beach, for heaven's sake.

The T was cool and clammy; outside, the day was even colder. Daylight savings time was just over, all the trees were leafless, and the streets got dark at five o'clock. Buenos Aires, Palm Springs, Algiers. But anywhere, really. Paris, London. No, not London. Or would it matter? What were the chances of her running into Matthew in a city the size of London? And what would it matter if she did? Paris, London, Rome. Anywhere, anything.

She tried not to look at the other people in her car. She read the advertising instead. Vodka, beauty school, Jobfinders, beer. The procedure to follow in an emergency was posted by the door in both English and Spanish, and she read it over and over. Pull the ring and slide the lever to the left, then follow the instructions of the train crew. An emergency seemed imminent. It always seemed to Margaret that people on the subway at odd hours looked disturbed in some way. Mornings, everyone going to work, they were absorbed in their newspapers or not awake enough to make trouble, and at the evening rush hour they were blank-eyed and exhausted. But during less busy times-like now, four in the afternoon-they weren't a crowd, they weren't safe. They were separate individuals, thinking. They were all potential maniacs.

Q: And what about me? I'm on the subway. Am I a potential maniac?

A: A maniac in potentia. Potential comes from the same Latin root as powerful, so you are a paradox: a powerless potential maniac. And so not really a maniac at all. You don't have the energy to be a maniac. Your maniacal days are past. Remember that.

En el caso de una emergencia por favor siga las instrucciones del personal del tren...How beautiful things sounded in Spanish. Majorca, Madrid, Managua, Manzanillo, all those warm and maternal words, everyone speaking Spanish, the food fiery with chiles, the hot blue skies continuing into the evening, and then the long, sweaty nights. Guitars. Bars. Men with cigars. The windows open to the stars. The doorways would be arched, carved into thick stone walls that were rough to the touch. Moorish. There would be flowers everywhere, everything red and yellow and lush, rampant green. She stared at an advertisement for shampoo that would make people want to smell her hair and thought: I've got to get out of here.

She was on her way to Cambridge, to see some people about driving their car to San Francisco. All right: San Francisco wasn't that warm, but it wasn't Boston, either. On the phone, the woman with the car-Mrs. Haskell, whose daughter at Berkeley needed their old Toyota-had said, "I suppose you've heard Mark Twain's famous comment, that the coldest winter he ever spent was a summer in San Francisco." Margaret hadn't heard it. The only thing she could quote from Mark Twain was the last sentence of Huckleberry Finnabout lighting out for the territory. She said she was thinking of doing that, and Mrs. Haskell had laughed tinklingly and said, "Oh, that's wonderful-the territory-because of course California still is in some ways such an uncivilized place, isn't it? I mean, compared to Cambridge."

She would drive the Haskells' Toyota to California, and she wouldn't come back. She could find a job, a neighborhood, people to live with. The main thing was to escape her parents and Roddie Smith and everyone else she knew and the cold city and the sidewalks full of dead brown leaves. The main thing was to chuck everything and start over.

At Park Street station, where Margaret changed trains, a young woman was singing. The song was a lament about a maiden fair, with rose-red cheeks and coal-black hair, the love that fades like the morning dew, the price you pay for a love untrue. No one was looking at the singer, though there were coins in the basket at her feet. Margaret dropped in a quarter: the price you pay for distraction. Then she leaned against a post and studied the singer-a mousy, overweight girl, who sang smiling. Her voice was shrill and powerful, like the voice of Joan Baez on an old record, echoing off the steel rafters and the mosaic walls, the posters advertising booze, the maps of the Red Line and the Green Line, the gleaming, frightening tracks-filling the subway station with (Margaret thought) madness. It was mad to stand there singing about lost love, singing for no one, singing for quarters. What could make her do that? Did she believe what she was singing? Did she wish as she sang that she had rose-red cheeks and coal-black hair? Had she experienced a love that faded like the morning dew? The station was strangely still, as if people were irresistibly, secretly listening. The voice was gorgeous, the song haunting. Margaret closed her eyes, and in the darkness the sound pierced her like a knife in her skin. When the Cambridge train came she was thankful.

All the way across the river to Harvard Square, she huddled in a corner of the car with her sunglasses on and the collar of her shirt pulled up around her ears. The thought of Cambridge still filled her with terror. She had dropped out of Harvard in April with her junior year unfinished. Officially, she was on leave. They would take her back, she knew. They longed to take her back. She felt Harvard's kindly, fatherly hands on her shoulders wherever she was, but it was worst of all at the Square. She never went there anymore. Even going through on the subway was risky, and Porter Square, where she was headed, couldn't be more than a mile from Room 105, in Emerson, where she had disgraced herself. She always thought of it that way, probably because her mother had said, "Well, you've finally disgraced yourself," as if disgrace was what she had been waiting for since the day Margaret was born.

Buckingham Street was three blocks from the subway station, a street lined with planer trees, which her mother poetically called sycamores and which always seemed to Margaret to be diseased, their bark tumorous and scabbed. Number seventeen was a brick house with a fanlight over the door. As soon as she saw it, Margaret knew she wasn't going to be hired by Mrs. Haskell to deliver her Toyota to California. She imagined a patrician old lady, honest gray hair in a bun, flowers on a polished table, thin Yankee lips pursed in disapproval of Margaret's punky hair and purple nails. And now that Mrs. Haskell had had time to think about it, would the name Margaret Neal sound familiar? Wasn't there a Professor Haskell in the English Department? Would Margaret's disgrace have reached as far as Buckingham Street?

She passed by the house, crossed the street, and backtracked to Mass. Ave., where she turned in the direction of Harvard Square. She hadn't had her Daily Suffering yet. Not getting the Toyota wasn't enough. She had known that particular dream wouldn't come true. No: her Daily Suffering would be to walk through the Square. Maybe even stop in the Coop or get a cup of tea somewhere or stroll through the Yard, past Emerson. No, not that. Just the Square.

Q: Can I keep my sunglasses on?

A: Yes, even though it will be almost too dark to see by the time you get there. You'll see well enough to suffer. If you don't, you're honor bound to take off the sunglasses.

She was wearing a flannel shirt over a turtleneck and a long, deeply flounced skirt, tights, and lace-up boots. Everything black except the shirt, which was black-and-blue plaid. One of her mourning costumes of the second rank. And then the sunglasses. Earrings long enough to bang against her jawline when she walked. She looked at her reflection in shop windows: a dry cleaner, a liquor store, Erewhon, a craft store with a window full of patchwork quilts, rag dolls, duck decoys with every painted feather in place.

She pushed her sunglasses up on her head and studied herself against a pink-and-white quilt. How wholesome the quilt, how dolesome the Margaret. A woman in the shop smiled dubiously out at her, raising her eyebrows. Coming in, dearie? Want to buy a nice dead duck? Margaret pulled down her sunglasses and went on. She tried to think what she could do after she negotiated the Square. She could call Felicity, whom she hadn't spoken to since April, and arrange to meet her for dinner at Adams House, ha ha. She could call Roddie and get him to take her to a movie. She could ride the T back to Boston and walk around the city and get dinner someplace and see a movie by herself. She could go home. She could make a beautiful, hand-crafted, one-of-a-kind noose in decorator colors out of her mother's needlepoint yarn and hang herself from a beam in the attic.

Harvard Square was darkening. The cars had their headlights on, and the neon Out-of-Town News sign was red in the gray air. At the Coop corner she waited to cross. This was going to be uneventful. She saw no one she knew, and no one looked at her. Dressed all in black, maybe she could disappear into the darkness. Cars zipped by. A homeless woman snored on a bench, surrounded by bundles. Someone played a banjo. A man with Reagan's picture on a stick was passing out bumper stickers that read no more shit, and Margaret took one. A girl in a Stanford sweatshirt jogging by bumped into her and said, "Whoops." Just then, she spotted Felicity.

Felicity was crossing Brattle Street with a boy Margaret didn't recognize. They were deep in conversation, Felicity doing most of the talking, sticking her teeth in the guy's face as she always did when she got excited. "You know?" Margaret knew she was saying. "You know what I mean?" The boy nodded, grinning. He was unremarkable looking, one of those people it was impossible to describe-the kind who get away with crimes. Well, officer, uh, brown hair, and some kind of eyes, I don't know, sort of average height, I guess...

She followed them across the street. He walked with his hands in his jacket pockets and Felicity held on to his arm. He was perhaps an inch taller than she, so that would make him five feet eight. Wait: Was Felicity wearing heels? Margaret maneuvered until she could see. Sneakers, both of them. Okay, then, five feet eight. Brownish corduroy jacket, the same dead color as his hair. Narrow shoulders. The skinny drippy preppy type Felicity always said she despised. Behind them there were two women with shopping bags, then a caricature of a professor (gray crew cut, tweed jacket, briefcase), then Margaret. If Felicity and Mr. Blah turned around they would see her instantly. Margaret took off her sunglasses. The risk would be part of D.S.

Still talking, they turned into Au Bon Pain. Margaret stopped dead, and the crowd parted around her and went on, oblivious.

Q: Do I have to go in there?

A: Decide for yourself.

She imagined herself going in after them, ordering a greasy spinach croissant, following them to their table and sitting down nearby. Or would they just be getting coffees to take out? Okay, she'd stand at the counter and order a cup of tea with milk in a loud, clear voice. Felicity would turn and look at her. Felicity would-what? Puke? Scream? Laugh? What could Felicity do that wouldn't be horrible in some way? Even if she sank to her knees on the phony Frenchy black-and-white tile floor and begged Margaret's forgiveness. Even if she pretended nothing had happened, yelped with joy, and hugged her.

No. Forget Au Bon Pain. Even for Daily Suffering, that was too much. She put her sunglasses back on and stood outside by the door. Here, in better weather, people sat at tables; here she had sat with Roddie, with Felicity, with fun fellow students, discussing professors and theses and movies and vacations and the weather. Normal life, she thought. Had that been normal life? She imagined herself being interviewed, at some point in the future, by some big-shot evening-news type. They are back in the Square-scene of her quaint youthful peccadilloes. She has a streak of gray in her hair, like Susan Sontag. She crosses her legs; her legs are spectacular; the camera pans back. She smiles off into the distance and says, It seems so long ago. We were all so young.

She looked through the window. Felicity and John Doe were sitting at a table eating pastries and drinking coffee, still talking. How could they have been served already? How long had she been standing there? She felt chilled with horror and also with the cold. I have to get out of here, she thought. I am going crazy for real.

A small wind had come up, and the sky was darker. She headed back toward the subway station. She took the bumper sticker out of her pocket and looked at it: no more shit. Easy to say, but where else was there to go but home?

She wrote to her cousin Heather, the only person she knew in California. Heather was twenty-five and had graduated from Berkeley and was working in San Francisco as a paralegal. Heather had been a fastidious teenager who spoke to Margaret only to give her advice about personal grooming. Head & Shoulders for dandruff but follow up with a good-smelling conditioner because Head & Shoulders smells like Lysol. Baby oil on your elbows but make sure you rub it in good or you'll get grease spots on your blouses. Hand lotion on your neck or else when you're old it'll get all stringy like your mother's. They had met a couple of times since then, at family events, and Heather seemed improved. The Thanksgiving before, at Aunt Nell's, they had had a long heart-to-heart about Heather's boyfriend, Rob, who was some kind of banker. Heather was getting tired of him. Rob was obsessed with the West Coast club scene, Heather said. Margaret thought that made him sound interesting, for a banker, but Margaret knew he couldn't really be interesting or he wouldn't be seeing Heather.

She rummaged through her desk for some decent paper to write on. She used her desk to store the junk of her youth, and she had to sift through letters and stickers and school papers and stuff about beekeeping, the English royal family, and the Boston Red Sox-some of her obsessions over the years, most of them from when she was eleven and twelve. Almost all the letters were from the Swiss pen pal she'd had during that time, Annette Brise. They were all in bad English; hers to Annette had been in bad French and quite dull: ici ca va bien, she always used to write, forgetting the cedilla. Margaret's mother had bragged so much about that correspondence that she had to end it, even though she liked writing to Annette and liked getting installments about Annette's crush on a boy named Denis: an affair of the heart, she called it.

She found some old stationery with her name and address printed on it, one of her mother's efforts to encourage her to keep writing to Annette. She took it downstairs to the kitchen, made herself a cup of tea, and sat looking at the sheet of notepaper, wondering what to say. Elegant black letters against cream, and the same address she'd had since she was seven, except for Harvard. It hadn't felt like her address for a long time: it was her parents' house, which meant that she was homeless. The Globe was folded up on the table; she could just see the headline, concern for homeless tops on dems' campaign agenda. She imagined Dukakis and Gephardt and Jesse Jackson getting together to buy her a plane ticket to San Francisco.

Dear Heather, I'm thinking of lighting out for the territory-namely California, preferably San Francisco. I'm getting fed up with the East, the weather, etc. What would you advise in terms of finding a job, a place to live, people? I have no money and will be lucky if I can get out there at all, but if I did-do you know anybody who needs a roommate? Do you have any ideas about where I could apply for a job? Are jobs hard to find? Around here, everybody has Help Wanted signs up. I mean waitressing, working in shops, etc. I'm not looking for demanding intellectual work. I'm sorry to lay this on you, I know you're busy, but you're my only contact out there. For any assistance you can give, the undersigned will be eternally grateful. Love, Margaret

She put it in an envelope before she could think about how stupid and desperate and pathetic it sounded, found the address in her mother's address book, and took a stamp from the monogrammed brass stamp dispenser her father had given her mother. She wondered if Heather had heard about her disgrace. Would her mother have told Uncle Teddy? No one would tell Aunt Kay because no one in the family was speaking to her, but her mother had these weird moments of intimacy with her brother, late-night phone calls with a lot of laughter, sometimes tears. Margaret wondered if there had been long-distance tears over her disgrace––or long-distance laughter, which would be even worse. She couldn't imagine her mother laughing over it: enough to make strong men weep, was one of the dumb things her mother had said. But what about weak men like Uncle Teddy? Enough to make weak men laugh, and then call Heather up and chuckle over it with her? I've got to tell you the latest about your cousin Margaret, she got involved with her English professor and then the guy dumped her and she had an abortion and a nervous breakdown and dropped out of school and got this weird haircut and has done nothing since April but sit around the house feeling sorry for herself and driving Lucy and Mark crazy. Isn't that hilarious?

No. Not even an alcoholic nutcase like Uncle Teddy, who wore a smoking jacket, sang Gilbert and Sullivan patter songs, and called her mother Pieface. Uncle Teddy wouldn't laugh; he would sympathize. His own life was full of similar disasters and humiliations. She should take off for Providence and get him to adopt her.

Boring though Heather was herself, Margaret always considered her lucky to be part of an interesting family-a father who wrote books and drank, an anorexic drug-addicted sister, a born-again redneck brother, a mother who had deserted them all. Compare that to being an only child with a mother whose main interest in life was keeping everything neat and a father whose idea of fun was to talk about how much it all cost.

She walked down to the mailbox at Cleveland Circle. She could take that walk in her sleep-often did, actually. Awake, asleep, there wasn't all that much difference. The sun shone grudgingly, and off in the distance a huge black storm cloud was riding in from the ocean. It was malevolent-looking, more like a mass of pollution than a natural phenomenon. As she watched it, the sun disappeared again, and she noticed that a similar cloud was approaching from the other direction. They would meet within the hour over Cleveland Circle, she thought. They would meet right over her head, and the heavens would open.

She mailed the letter, walked around for a while looking at the shops, and bought a copy of House and Garden at the AM/PM store. Then she went into Eagle's Deli and ordered a cup of coffee. For her Daily Suffering she would walk home in the downpour.

Q: Is that good enough?

A: Probably not. We'll see.

She opened House and Garden and read an article about an English family with a hyphenated name who lived in a renovated Victorian horse barn. Their children were James, Charlotte, Alexander, Emma, and Tony. Charlotte was fourteen and had her own studio to paint in. Little Tony had his own playhouse, a hundred years old, with a thatched roof. The stables were like a palace. It would all be jolly good fun for the homeless: fifteen rooms, sixty acres, Hepple-white beds, Chippendale chairs, antlers on the wall to hang hats on, everything dusted by servants, and, through the silk-curtained windows, views of the lime walk, the dovecote, the bell tower.

Margaret loved House and Garden. For years, she had given her mother a subscription every Christmas, until her mother refused to read it anymore. She claimed it was a frivolous and decadent magazine. Margaret had asked her if it wasn't more frivolous and decadent to live that way yourself than to read about other people living that way. Her mother had said what nonsense, they didn't live that way, and Margaret had said that they would if they could, wasn't that what this house was all about? Antiques and china and expensive tea and those five-dollar cans of oatmeal imported from Scotland. Admit it, she said––you'd love it if I called you Mummy. And her mother had said you are an absurd, ridiculous girl, you are truly pathetic, you have lost contact with reality.

The rain started when she was halfway through her second cup of coffee, and she left without finishing it in case the rain stopped prematurely. It was a tentative rain, but she was glad to see that it increased as she walked. She put the magazine under her sweater and lifted her face to the clouds, which were now a solid gray mass over her head. In the west there was a window of blue. California, she thought. Water dripped down her neck. She wondered if her earrings would rust. Too bad: part of D.S.

She thought about Roddie, the only person who knew about Daily Suffering. He had said he would do it too, and he probably did for a while, but she was sure he wasn't doing it any more. Not that he didn't feel bad about it-he agreed with her that abortion was an important right for poor black teenagers, etc., but wrong for healthy young spoiled white women who had gotten pregnant through carelessness and a feeling of invincibility. They both knew they should have gone through with it, let the baby live, gotten married or at least had it adopted.

But Roddie didn't feel bad about it quite the way she did. If she knew he felt bad enough, she might want to see him. But he hadn't had the nausea and the swollen breasts, he hadn't had a little thing with arms and legs and a brain scraped out of him, he hadn't bled buckets, he hadn't been told he was a disgrace.

This particular Daily Suffering hadn't seemed like much when she decided on it, but by the time she got home she was soaked through, her teeth were chattering, her feet were frozen. When she looked in the mirror her ears and her nose were bright red, the rest of her face dead white, her hair plastered down to her head like molasses. She thought with satisfaction that she had never seen anything so ugly. Oh you lovely young thing.

She ran a hot bath and took off her clothes, shivering. No heat until November first, that was her father's inflexible rule. She threw everything down the laundry chute, even though her mother had made her promise never to throw clothes down wet because of mildew. She stepped into the tub and submerged everything but her head. She had forgotten to take off her earrings, and they were cold against her neck. Even under the hot water, her feet and her knobby knees stayed bluish. She would never warm up. This would be the Ultimate Daily Suffering, to stay cold forever until she froze to death like her mother's aunt Peggy had: until her blood froze in her veins, her brain hardened like a flower after an ice storm, her eyeballs became marble eggs, her heart a Popsicle, her toes and fingers deader than wax...

She ended up in bed for a week with a major cold. Her mother had been in Vermont taking photographs, but she got home just in time to keep Margaret supplied with vegetarian broth and fruit juice. She put the antique cowbell next to Margaret's bed for her to ring when she wanted anything-an old Neal family tradition. Her mother loved it when she was sick, Margaret could tell; it made her a dependent again, a mother's dream: a daughter whose biggest disgrace was her runny nose.

When her father was home, he answered the cowbell. He stood in the doorway and said, "Your wish is my command." To prove, contrary to all appearances, that he really did love her, he would go out and get her anything. Mocha lace ice cream, Soho black cherry soda, spinach croissants: nothing was too much trouble except normal conversation. He would bring her what she wanted, ask her how she was feeling, tell her to keep drinking liquids, and return to the basement where he spent his evenings caning chairs and refinishing furniture. He went to bed at 9:30 every night because he had to leave at 6:30 in the morning to avoid rush hour. He was a research physicist at a lab in Watertown. Her mother stayed up half the night and slept the mornings away. For a long time Margaret had wondered how they managed their sex life until it finally occurred to her that they didn't have one.

She and her mother looked at the Vermont photographs together-the usual product, just right for the annual calendar that was her mother's one claim to fame. This would be its eighth year: Lucy Neal's New England Visions, A Portfolio for All Seasons, it was officially called––a small but steady seller. Tourists loved it: arty black-and-white views of churches and birches, kittens curled up in baskets made by Native Americans, wheelbarrows, picket fences, village greens with harmless old cannons, hay wagons piled high with pumpkins.

"Pick two," her mother said. "We're looking for October and November." She sat at the foot of Margaret's bed, curled up like a kid. Margaret shuffled through the photographs and picked out one of smiling children in Halloween costumes and one of a broken-down fence and leafless trees twisted against the sky. Her mother frowned over them, her light curly hair falling in her face. She tapped her top teeth with one fingernail. Her fingernail was ragged, her cuticles bitten. Her lips were chapped, so she had smeared Vaseline over them. She wore a baggy blue sweater and faded jeans and a necklace made of moldy-looking greenish chunks of something. In contrast to the house, she always looked like a slob.

Her mother said, "I don't know, I don't know, I'm not sure about the trees. They're so depressing." She sighed, but Margaret could tell she was really in a good mood. There were times when her mother's unhappiness was massive and scary, a force that appeared out of the blue and permeated the whole house like poison gas. Margaret sometimes thought her mother must have a secret life that preoccupied her, that dictated her mysterious ups and downs-a lover in Maine or Vermont, where she took her photographs, or in New York, where she was always going to see her art director. When Margaret was feeling generous, she hoped this was true, though it was hard to imagine. Roddie, whose tastes were bizarre to say the least, thought her mother was good-looking.

Her mother asked, "What about the basket of acorns?"

"You did a basket of pinecones two years ago." Margaret had had the calendar in her room at Adams House. That November-the pinecone November-she had met Roddie. She had circled November twenty-ninth in red because that was the first time they had slept together. Big deal. She had thought it would lead to better things, but it had only led to a blob of blood and tissue thrown out with the trash at Cambridge Hospital. She counted back in her mind: Roddie hadn't called her in two and a half weeks.Gloria in excelsis Deo.

Her mother finally decided on the trees and the broken-down fence, and she praised Margaret's taste. For years, she had paid compliments meant to encourage Margaret's artistic talent. She thought Margaret should be a painter. Margaret hadn't painted in years, not since high school. She hated to think of the paintings she had produced, the lame attempts at drama and shock (a dead squirrel she found in the backyard that she painted in various stages of decomposition, a sequence of dead flowers in expensive cut-glass vases) and the cheap symbolism she sometimes attempted as a commentary on current events-like Reagan grinning on a television screen that was really a coffin. She knew she couldn't paint, even if her mother didn't have the sense to realize it. Or maybe her mother did, and encouraged her anyway because she was perverse, or because she wanted Margaret to be mediocre, or because she wanted Margaret to get off her butt and back in touch with reality.

Except that now she was exempt from getting off her butt because she had a cold. She wondered how long she could hang on to her precious germs. She thought about writing a poem, "To a Virus," the way poets used to write poems to mice and fleas. Hail thou microscopic beastie. On my blood thou hast thy feastie. It was pleasant to be sick. Her father ran errands for her. Her mother made hot toddies, lentil soup, custards. She framed a print of the trees and gave it to Margaret to cheer her up, propping it on the top shelf of her bookcase between the pottery vase full of chrysanthemums and the old-fashioned wind-up alarm clock.

Her mother's passionate quest for domestic perfection usually seemed to Margaret a form of insanity-everything relentlessly clean, tidy, and aesthetically pleasing, the whole house a monument to anal retentiveness. Or to her parents' empty marriage. Or her mother's vague but stifled creativity. Whatever. But when she was ill she liked it. Sunlight, flowers, neat bare surfaces-they made her feel pampered, like a movie heroine with a wasting disease, someone beloved who would be missed when she was gone. Everything was ready: the camera crew could move right in, wouldn't have to touch a thing. Just dab some makeup on her red nose.

She liked the tree photograph. It would be one of the things she would take to California, as a souvenir. It was perfect: dead-looking trees, photographed by her mother.

"It looks nice on the shelf," Margaret said.

"It's pretty bleak," her mother said dubiously.

"It's supposed to be bleak, Ma. November is the bleakest month."

Her mother smiled at her, as she always did at the hint of a literary allusion, any evidence that nearly three years at Harvard plus a home life rich in culture had done its work. "Are you reading anything good?" she asked. "Besides House and Garden?"

Margaret held it up, open to the stables people. "James goes to Oxford, Alexander's at Eton, and Charlotte's won the watercolor prize three years in a row at her school. And look-that's Tony's little playhouse."

"Please, Margaret," her mother said. "Let's not have our House and Gardenargument again."

"I'm also reading Middlemarch."

"God––what's that? The fifth time?" Her mother used to be proud of her for reading it so many times. Lately it was worrying her. It was like when Margaret was eleven and used to read about keeping bees. She wrote to the Department of Agriculture and the National Beekeepers' League for pamphlets, and subscribed to an English publication called The Apiarist. Her Bible had been The ABC and XYZ of Bee Culture. At first her mother thought it was cute, an eleven-year-old who knew, and would tell you, that bees won't fly unless the temperature is at least 55 degrees Fahrenheit, that drones have 37,800 olfactory centers in each antenna. Then she started thinking it was weird, and kept trying to distract Margaret by buying her things: a boom box, a fish tank, a set of wooden chickens that nested one inside the other like Russian dolls, an Alice in Wonderland pop-up book from the Metropolitan Museum of Art that was much too young for her. Also, that was the summer they went to England. When the beekeeping craze was safely over, she heard her mother say to her father, "I suppose she getssomething out of these obsessions," and for years afterward she wondered what she had gotten out of her love for bees besides a love for bees.

"Or the sixth?" her mother asked, picking up Middlemarch and squinting at the painting on the cover: a woman in a fussy Victorian dress, languishing in an uncomfortable-looking chair.

It was only the fifth time, but Margaret said, "Seventh."

At the end of the week, when she was beginning to feel better, a postcard came from Heather. Fast work: hard to believe, from a cousin whose busiest moments used to involve putting three coats of polish on each nail and drying each coat separately in a nail-drying machine she had conned Uncle Teddy into buying her. Margaret was glad she was home alone when the mail came; her plans were private, as Heather should have known. Margaret assumed she did know, and that was why she'd chosen to expose them on the back of a postcard.

She took the card up to her room to read it. In her tiny cramped printing, Heather said that if Margaret was serious about coming to San Francisco, she should get in touch with Rob at his bank, where they always needed teller trainees, though the pay was lousy. Heather and Rob were in the process of breaking up. Heather was living in a tiny studio apartment, but she might be able to put Margaret up for a night or two if she didn't mind sleeping on the floor. There was a PS.:

As for the weather, you've probably heard Mark Twain's famous line that the coldest winter he ever spent was summer in San Francisco, so don't expect much.

Margaret turned the postcard over: a tinted photograph of a 1957 Chevy in front of a hot dog stand with carhops. She tried to visualize someone going into a shop and actually buying this card. Then she read Heather's tiny cramped printing again and decided the message was hostile. But it told her one thing she needed to know: avoid Heather like the plague. She ripped the card into four pieces and tucked them in her sweatshirt pocket.

Her mother was out at the supermarket, so she couldn't ring the cowbell. She blew her nose and went down to the kitchen to make tea. She hadn't had a cup of tea since she got the cold: tea with milk tasted terrible when you had a cold, like drinking mucus, and she hated tea plain. She put Heather's postcard down the garbage disposal and put on water for a pot of Jackson's Queen Mary, her favorite. While she waited for the kettle to boil, she stared at a photograph hanging over the sink: herself at fourteen-one of her more awkward ages-wearing a denim jacket and trying to look tough, but looking, in fact, harmless to the point of geekiness-which was why her mother had framed the thing and hung it on the wall. God forbid she should just thumbtack it up. That photograph was one of the million things Margaret wanted to escape. If she made a list of them, it would stretch from Brookline to San Francisco.

She carried the tea and a tin of shortbread cookies upstairs on a tray. She had planned to pig out on cookies washed down with tea and make a leisurely list of her options, but before she took three bites it was clear to her that her only hope was Aunt Nell-her mother's aunt, actually, a no-nonsense ex-schoolteacher who wore sandals with colored cotton socks and was probably a lesbian. Aunt Nell was the only one of her generation left, and she had all the money.

But Margaret hesitated to ask her, not because she thought her aunt would refuse but because she was pretty sure she'd agree. It made her feel guilty. What did the old lady have in her life? A cat. A big old house full of stuff nobody wanted. Bran cereal and prunes. Relatives who coveted her dough.

When Margaret was little she used to like going to Aunt Nell's every year for the big family Thanksgiving dinner. She and her parents always stayed overnight. There was always a cat, that Aunt Nell always named Dinah. There was an antique bed with pineapple posts. There was the dusty attic where she could take the cat and hide from her cousins. There was Aunt Nell's friend Thea, who kept chocolate kisses in the pocket of her apron. There was Aunt Nell herself, who at some point always used to tuck a folded ten-dollar bill into Margaret's palm and say, "This is for you to spend, don't tell your parents about it."

As Margaret got older she dreaded those reunions. Her cousins always seemed to be going through unpleasant stages. After Thea died, Aunt Nell became crabby, and the food wasn't as good. And it was boring there-nothing to do but pet the cat or sneak away with a book or be snubbed by Heather or watch Uncle Teddy get drunk. She was still fond of Aunt Nell, and sometimes thought of going up to Syracuse to visit her, but she never did. She couldn't believe she would be anything but a burden, an awkward young niece who didn't have a lot to say. After Thea's funeral, when they were all up at her aunt's house eating lunch, Margaret had tried to tell her aunt how much she had liked Thea, how sorry she was, and Nell had been mean to her for the first time in her life-brushed her aside, said it didn't matter, what good did anyone's sympathy do.

She sat on her bed and finished the tea and cookies. She tried to empty her mind by staring at the alarm clock. The tick was so loud she couldn't actually use the clock, and when she was eight years old she had permanently stopped it at 8:13, which someone told her was the time Lincoln was shot. She used to stare at the Roman-numeraled face until she got double vision and began to feel dizzy, and then she would close her eyes, open them, and something significant would come into her mind. She tried it, but the only thing that came into her mind was the doctor who had scraped her clean, Dr. O'Something, she could never remember, trying to hide his disapproval behind an unconvincingly brisk manner, calling her "Ms. Neal," scribbling on her chart and refusing to look her in the eye.

Q: Should I or shouldn't I?

A: Go ahead. See if you can take advantage of an old lady on top of everything else you've done.

She went to the desk for more stationery and wrote:

Dear Aunt Nell, I wonder if you could lend me the price of a plane ticket to San Francisco. My parents are still mad at me for leaving Harvard, and I'm afraid to ask them for anything. In fact, I try to stay as unobtrusive as possible around here. I've been in touch with Heather, and she has promised to look after me, help me find a job, etc. But I can't make any definite plans until I have plane fare, which I figure is about $250, say $300 (one way), although I'll fly the cheapest airline possible and send you back any extra. I hate to ask you, but you've always been so good to me, not that that's a good reason, I don't like to impose on your goodwill, but I'm really desperate. I've had so much bad luck in Boston and vicinity that I just feel the need to make a fresh start somewhere. So for any assistance you can give, the undersigned will be eternally grateful. Love, Margaret.<

PS. Good luck with selling the house and your new condo. I guess we'll see you at Thanksgiving unless I'm in California by then-???

Margaret took the letter downstairs. She was definitely beginning to feel better. Writing the letter had helped, even though it might annoy her aunt to death and was riddled with lies. It wasn't true, for instance, that she was afraid to ask her parents for the money; the problem was that she was too proud, and she didn't want to endure the lectures that would accompany their refusal. And Heather wasn't going to look after her. And she wasn't planning to refund any extra money she might get beyond the plane fare. And she was going to do her best to avoid the usual family Thanksgiving. But a lot of the letter was true: her bad luck, her eternal gratitude, even Love, Margaret. She did love her old auntie.

She put the letter out for the mail carrier to pick up and went back to bed. She definitely felt better, but she was in an uncertain state, neither sick nor well, so that she didn't know whether or not the cold still qualified as D.S. or if she should find something else. Could Heather's postcard count? It had involved a certain amount of mental anguish. She decided to give her illness one more day, settled back into the pillows, and sank like a stone into the familiar troubles of Middlemarch.

Sometimes she dreamed about Matthew. She always thought of him as Matthew, though in real life she had never called him that. She had called him Mr. Nicholson like everyone else. The dreams were very boring. He was walking down a hall, usually with his back to her, his wild white hair flying around his head. He was sitting in an airport on a blue plastic chair, looking mournful, a suitcase beside him. Once she had a wonderful dream where he was in a garden smiling at her-at least, she hoped the smile was for her, but she realized when she woke up that it could have been directed at anyone.

Sometimes she woke up from the dreams missing him and humiliated. For a while after the abortion she thought constantly about being in bed with him. She had hated making love with Roddie, always. She never got to like it better, even back in the days when she liked Roddie's long, dopey face and sweet smile.

With Matthew it had been completely different, in spite of the amount he'd had to drink. When Roddie was drunk he was a dead weight, half-asleep, and things were worse than usual. But Matthew had been wonderful. The booze hadn't made him tired, it had made him reckless and loving. He had taken such care of her; he had taught her to like sex the way he had taught her to like the Augustan poets. She had been nothing, and that long afternoon in his bed he had made her into something.

He was English. His wife had recently left him. He was at Harvard just for the year. He drank too much. He was forty-two. All this was common knowledge.

First semester, Margaret took his Age of Pope course; second semester she and Felicity signed up for Eighteenth-Century Prose. He used to invite his students to his apartment on Linnaean Street and serve them tea, with crumpets that were sent to him by his sister in London. They toasted them in the fireplace on long forks. It was like being in a novel by E. M. Forster or Evelyn Waugh. It was like being in the Bloomsbury group.

The day came when Margaret stopped by, alone, to drop off a paper, found him drunk, stayed to make tea and talk, and ended up in his bed. He had said, "Oh you lovely young thing, I should take you back to London with me." She remembered that perfectly: oh you lovely young thing.

Some days when she could think of no better Daily Suffering, she forced herself to relive it. First the good part, the afternoon of lovemaking: what he had done to her, what he had said, the light coming yellow through the drawn shades, the way he had murmured and held her, didn't want her to leave. Oh you lovely young thing in his beautiful accent. His funny cotton undershorts, his old-fashioned watch on the bedside table, his salt-and-pepper pubic hair. She had laughed at him, lovingly, and he had laughed at her, played with the tips of her nipples, used his tongue, and afterward there had been true peace, a state she had never experienced, and knowledge she had never had. Lying in that yellow room with Matthew, there was nothing she didn't understand. She was one of the enlightened, one of the elect.

She would go to England with him, become his mistress, and live in a state of continually renewed knowledge and pleasure and feeling. Her life had begun. Her life was a garden, like Twickenham-ordered and beautiful in a way she had always, before, assumed was closed to her.

She walked home in the misty dark. It was late March, and the trees in the Yard were coming into leaf. The streets were full of people who looked happy. There was a foggy new moon like a chalk mark on a blackboard. She had gone back to Adams House, told Felicity she had been at the library, and shut herself in her room so she could say it over to herself until she had it memorized, every move, every word, every touch of his hand on her skin.

And then nothing. He didn't answer her notes or return her phone calls. She went to his office during office hours and found he had canceled them. She rang the bell at his building on Linnaean Street and got no reply. He dashed out after class as if pursued by Furies. It took her a couple of weeks to realize he was embarrassed by their encounter. He regretted it. He had been drunk. Sober, he realized he had screwed a student-like Abelard. She cried herself to sleep every night but tried to be philosophical: she had had her heart broken. She wanted to be a writer, and she knew tragedy was necessary. Eventually she'd be able to make use of it.

Then she missed a period and panicked-but her panic contained a kind of elation. This he couldn't deny. She knew it was his. Roddie: She hadn't seen Roddie in ages. She had been avoiding Roddie for-how long? Long enough. Roddie was no one. It was not possible that sex with Roddie could produce a baby. Sex with Roddie was like a frozen dinner: barely nutritious and certainly not creative. If she was pregnant, it was Matthew's baby. She pictured a little English child, a boy in a sweater and short pants, climbing over a stile.

She told no one. She missed another period. She had mild nausea in the mornings, which she hid from Felicity. She went out with Roddie sometimes but she wouldn't sleep with him. She reread Middlemarch. She cut classes and owed papers to everyone, including Matthew. Her other professors hounded her for them; Matthew never said a word. She lay awake crying, trying to make a plan. The end of the semester was approaching. She knew he would be leaving for England soon. I don't want to miss a day of the English summer, he had said. Oh you lovely young thing, I should take you with me.

She finally confronted him in the hall before class because she didn't know what else to do. She clutched his arm, hung on to the rough tweed of his jacket, told him she was pregnant, asked him why he didn't want to see her. She had wept and been noisy. There had been students all over the place, shock and awkward laughter, Felicity and Alan and Jessie Henley and Peter Green and everyone else staring in amazement. He had said-she remembered this even better than Oh you lovely young thing-he had said, "My dear young woman, I haven't the faintest idea what you're talking about," and looked over her head at the collected crowd as if he expected them to save him. She had seen that look: fear was in it, and bewilderment, and incredulity not untouched with amusement. It was so convincing that she wondered if she was going crazy. She certainly felt crazy. Had she dreamed it all? Had she read it in a novel? His long kisses, the funny English undershorts with buttons, the ice melting in the whiskey glass beside his old-fashioned watch?

They took her to University Health Services, and a psychiatrist talked to her. Then she was examined by a physician. They did a pregnancy test. She was talked to by an abortion counselor. Then by the head of a women's group that wondered if it had a sexual harassment case. Then by the psychiatrist again, who explained that Professor Nicholson had had a vasectomy years ago, he had offered to call London and get the documents that would verify it-not that that was necessary, of course. Professor Nicholson was very concerned about her. He had been fond of her, she was one of his best students.

Her mother came, tight-lipped and red-eyed, elaborately kind at first but moving quickly to words like disaster, disgrace. Then Felicity, who said, "I keep trying to understand you, Margaret. I keep trying to have sympathy for you. But I can't figure out how you could act like that toward someone you supposedly liked and respected." Then Roddie, who put his head in his hands and said, "Oh Christ, this is going to wreck my whole life."

They took her from UHS to Cambridge Hospital, where Dr. O'Whatever performed the abortion. She quit talking to Felicity, and she told Roddie she couldn't see him for a while. She met with a counselor who arranged for her to take a leave. It turned out that on top of everything else she had a very mild case of mono. Her father picked her up at the hospital and drove her home to Brookline, a ride across the river that was perfectly silent except for a Mozart horn concerto on the tape deck.

Roddie called and asked her to meet him at Lulu's. "For what?" she asked.

"I just want to see you."

"For what?"

"Not for anything, Margaret. Just for the hell of it. Just to get together."

"I'm not sure I see the point."

"Oh, for Christ's sake, then forget it," he said, and hung up.

She called him back and said, "All right. I'm sorry. I'll meet you at Lulu's."

"For what?" he asked.

"I've got something to tell you."

"Good or bad?"

"Neutral."

There was a pause, and then he said, "I've been missing you."

"I've had a cold," she said, as if that explained why she hadn't been missing him.

They met at Lulu's the next afternoon. Since she had left Harvard, they always met at Lulu's, a lunch place near the Museum of Fine Arts. The nearest school was Northeastern. The chances of her seeing anyone she knew at Lulu's were very small.

She wore her black jacket and black jeans: mourning costume of the first rank. She was late. When she arrived, Roddie was eating a hamburger at a table near the back. He half-rose when he saw her, then sat down again awkwardly. She took off her jacket and sat across from him. They exchanged half-smiles.

"Sorry about the hamburger," he said. He had never stopped feeling guilty because she was a vegetarian and he wasn't. She didn't say anything, just sat and watched him eat. A waitress came over and asked her if she wanted anything, and she ordered a cup of tea.

"Make it two," Roddie said. He finished his hamburger, wiped his mouth prissily with a napkin, and pushed his plate away. There were dribbles of blood and fat and ketchup on the plate. He dropped the napkin over it and said, "So what's your news?"

Now that she was with him, she didn't want to tell him. There was something about Roddie that made her feel as if she had died. It was hard for her to speak. Even to move seemed more trouble than it was worth. Every time she sat with him in Lulu's she felt she would sit there forever because she'd never have the energy to get up.

"It's not really much," she said finally. "I'm moving to California."

The waitress set two cups of tea on the table, scribbled out a check, and tucked it between the napkin holder and the sugar bowl. When she left, Roddie said, "Sometimes I wonder about you, Margaret. What do you mean, not really much? You're moving to California and that's no big deal? What do you mean, you're moving to California? To do what?"

She couldn't stand the way he got excited about things. Not the fact that he got excited, but the way he did. He always started out calmly-he knew he had a problem-but then his eyes popped, he spit saliva, he gestured wildly, his voice got loud and wobbly.

She sat silently, watching him. He waited for her answer, gave up, and went on. "I wish you would approach things like a normal person, Margaret. I wish you would just be honest and open and not be putting on this act all the time." He reached across the table and wound his fingers around her wrist. "You don't have to be supercool with me, you know. You can admit that moving to California is a very big deal. I don't understand this. Why are you moving to California all of a sudden, anyway?"

She looked down at his skinny, black-haired fingers. Her hand in his grasp looked pink and frail, a small, trapped animal. She wiggled it but he held on tight, and she sighed. "I'm not even sure I'm going," she said. "It depends on whether my great-aunt sends me the money. She probably won't. I'll probably be stuck in that house with my parents for the rest of my stinking life. Forget California. Forget I said it."

He let go her wrist and put sugar in his tea, stirring it violently, and took a slurp off the top. "Do you want my advice?"

"No."

"Think it over. I'm a smart guy."

"No, thanks."

He looked at her in squinty-eyed silence, nodding his head as if she were some rare species he was on the road to figuring out. He was a double-concentrator in biology and computer science. He was doing his thesis on the comparative radar systems of Myotis lucifigus, otherwise known as the little brown bat, and its larger cousin, Eptesicus fuscus. One of his many minor interests was vintage rock-and-roll. He had recently sent an article toPopular Culture Review about the influence on the Beatles of old rock-and-roll songs-of "La Bamba" on "Twist and Shout," "He's So Fine" on "My Sweet Lord," "My Boyfriend's Back" on "Sgt. Pepper." A thousand and one nights listening to the Shirelles in Roddie's room at Lowell House.

He drank more tea, spilling it. "You know what's your real problem?"

"Yes. My real problem is how to get out of this city before winter."

"No," he said. "That is not your real problem."

They sat staring at each other. She didn't want to stare at Roddie-she hated the way he looked, couldn't believe she used to think he was cute-but she would have lost points if she had looked away. It occurred to her that she wanted to know what he would say. She cocked an eyebrow at him. "Okay, Roddie," she said. "What's my real problem?"

"Guilt."

"Uh-huh."

"I mean it. You're reeking with guilt over the whole mess, the abortion, everything."

"We agreed not to discuss it, Roddie."

"We agreed on that last April, for Christ's sake, Margaret. It is now October, in case you haven't noticed, and you haven't progressed one tiny bit. For six months you've done absolutely nothing."

"Not true," she said. "I've done plenty of things."

"Name one."

She thought. "I had a cold." He started to speak again, but she said, "Forget it, Roddie. I don't want to hear it."

"Well, you ought to hear it. You ought to face things a little better. Okay, you screwed up, you acted like a jerk, and you and I were stupid, and you had an abortion, and you dropped out of school. Let's face it. You've had a lot of problems."

"Okay," she said. "Let's consider it faced. Now can I go?"

"Margaret." He ran his fingers back through his hair. He needed a haircut. She had cut it for him months ago, and it looked like it hadn't been touched since then. She fingered her own hair, the stubbly strips shaved around her ears.

She said, "I think you should wear one dramatic rhinestone stud in your left nostril."

"Just shut up and listen to me. Let me finish." He slurped his tea again and banged the cup in the saucer. "I'm being serious, Margaret. You can laugh all you want, but I'm giving you good advice. You ought to go back next semester. You could take your usual course load and finish up your incompletes and you'd only be a semester behind."

He was doing it again, the staring eyes, the jabbing finger, his hair standing on end. Oh God: Roddie. She was supposed to be fond of him. My boyfriend's back. Right. How could she not be fond of him? He was her first, her only serious boyfriend. She had lost her virginity with him. She had gone to bed with him a million boring times. He had impregnated her, hard though it was to believe. He was brilliant, he was having an article come out in Popular Culture Review, she used to find him attractive, and, worst of all, he was in love with her.

"You'd only graduate a year late," he said. "If you keep on the way you're going, you're not going to graduate at all."

She smiled at him and said, "Oh horror."

He pushed back in his chair, and the table lunged toward her. Their teacups and saucers slid off and crashed to the floor. Roddie paid no attention. He said, "God damn it, you don't seem to understand that I feel responsible for you. What the hell do you think I'm supposed to do? I can't write my fucking thesis, I can't do my research, I can hardly go to classes, I don't sleep at night-nothing. I think to myself, can I call her, do I dare, is she going to hang up on me or what? All I do is worry about you, and you sit there and laugh."

He calmed suddenly, made a distracted gesture toward the cups on the floor, ran his fingers through his hair again, looking helpless. The waitress hovered nearby. People were watching them, warily. Margaret put on her jacket and started toward the door. She saw Roddie count out some money. "Sorry, sorry," he muttered, following her. They went out onto Huntington Avenue.

"Get away from me," she said.

"No," he said, and took her arm. "Margaret, this is killing me. You never think about what it's doing to me. It's all you, poor Margaret, she's got to punish herself, but you're punishing me too, damn it. I'm suffering, Margaret. I don't need to manufacture any fucking Daily Suffering, I've got it all built in. I'm going crazy because of this."

At the subway stop he let go of her arm. They stood in silence. I will not cry, she thought. He will not make me cry. He'll get over this. I'll be gone. It doesn't matter. She turned her back to him and stared down the tracks, unblinking.

He said, "Margaret?" She didn't answer. "Margaret?" She could see the T coming, way down the block. She concentrated on trees. There were plenty of them around the museum, most of them bare like those in her mother's photograph, but not bleak. The sky behind them was a brilliant blue that looked fake-dyed by some sentimental optimist. When the car came, she got on and looked behind her for Roddie, but he was gone.

She did nothing but read. "You could occasionally do something more productive," her mother said. Her mother had also made several serious speeches about her going back to school. If not Harvard, then how about transferring somewhere else? How about Cornell? Her parents had both gone to Cornell, and had been hurt that Margaret wouldn't even apply. Or B.U.-nothing wrong with B.U. Maybe Uncle Teddy could get her into Brown for spring term. Or she could take a job for the rest of the year and start school again in September. Or at least do some volunteer work. One of the soup kitchens, a literacy program, tutoring in the schools.

Her mother's ideas ran down and finally ended with, "If nothing else, you could paint." Her smile eager, her eyes bright with stubborn hope.

Margaret hated it that they didn't force her to go out and get a job-though she knew she would hate the job even more. She didn't even have to do housework. They still considered her to be on the brink of some disaster: unbalanced, dangerous. They pretended she didn't revolt them, pretended she was their pet. After six months, her mother was still making all her favorite foods and doing her laundry. Her father was still coming up to her room when he got home from work and asking nervously, "So how's my girl today?"

She always said, "Oh, pretty good, Dad. Hanging in there," and he would do the fake grin he had perfected over the summer and say something like, "Hey-I see we're having tortellini for dinner. I'd better get down there and see how things are coming along."

She wished she had the guts to become anorexic or run away or join the homeless on Cambridge Common or at least go officially crazy. She imagined lunging at her father when he came in, making animal noises, slashing with her fingernails. Or tossing the bowl of tortellini through the dining-room window. She hated herself for wolfing down her mother's goodies, and for slopping around the house all day in her old sweatpants, reading. She was even beginning to resent the books she read: in them, things happened. Life went on. People went to work, dressed up, took walks, held conversations, got into their cars or their carriages and drove places. No one hung around in sweatpants and read about it.

She considered calling Roddie up and saying, "Okay, loverboy, let's get hitched." She considered showing up at his room with her wrists slashed, bleeding all over him: this is what blood looks like, Roddie, and she would smear it on his shirt, his face, his hairy hands. She considered calling him and saying she was in London, Matthew had sent for her, they were living together, and every night they went to the theater and then to a pub and then home where they screwed gloriously, royally, incessantly, so fuck you, buddy, fuck all of you.

She finished Middlemarch and reread Portrait of a Lady, and she tried and failed for the third time to get past page ten of Less Than Zero, and she reread The Beggar Maid and Mr. Bridge and was halfway through Mrs. Bridge when a package came for her in the mail from her aunt Nell.

It was the size of a paperback book, and it was wrapped in brown and tied daintily with white string. Her heart sank when she saw it. It certainly didn't look like anything that was going to get her to California. She tried to think what it could be. Aunt Nell had a sarcastic side. A guidebook to San Francisco? A rubber frog? A photo of her favorite auntie? Whatever it was, it looked like Daily Suffering, neatly packaged.

No one was home, thank God, thank God. Margaret took the package to her room and cut the string with nail scissors. Under the wrapping was a box that had once held Christmas cards-gold bottom and stiff plastic top, with tissue paper inside: tissue wrapped around small hard objects.

Margaret began unwrapping them. A ring, a necklace, more tissue, other things-all small pieces of jewelry, like prizes in a kids' game. She thought at first that she was meant to sell it to finance her trip to California, but the stuff was clearly worthless: a cheap necklace of blue glass beads, another necklace of fake pink pearls, a brass chain with an ebony pendant in the shape of a half-moon, an enamel ring, a cat pin, two thin gold bangles, and a scarab bracelet. Junk.

Then she saw that at the bottom of the box there was an envelope, square and white, with her name on it in Aunt Nell's handwriting. Aunt Nell wrote in blue ink with a broad-nibbed fountain pen, so that the letters were shaded and the writing looked formal and old-fashioned. The M in Margaret bore a flourish like a flag blowing in the wind, the t was crossed with a plumed streak. Could Aunt Nell write her name with such conviction if there wasn't a check inside? If there was no check, wouldn't she write in small, apologetic letters?

She waited. She looked at the jewelry, piece by piece. The ebony pendant was rather nice-and black, so she could wear it with her mourning clothes. The gold bangles were okay, not exciting. She put the ring on her finger-blue enamel with little pink flowers and souvenir of cold springs in yellow. Cute. Kitschy. So what?

The ring seemed familiar, seemed to have a vague unpleasant association, but she couldn't place it. She sat and stared at the way it looked on her finger, waiting. Then she studied her boldly scrawled name. Margaret. Margaret. Margaret.

The envelope, please.

Q: What's in it?

A: What you deserve.

She opened it. Inside was a folded piece of notepaper and inside that a folded check. The check fell out, still folded. Her stomach dropped, and she could hear her pulse beat. She read the note.

Dear Margaret, This is some of your great-aunt Peggy's old jewelry. I'm cleaning out the attic preparing to move, and I thought if anyone should get this, you should, since you're named after her and you look more like her every year. I don't think I'll have the family here at Thanksgiving this year. I'm between houses, and the place is in an uproar. Take care of yourself out in California, let me know how it goes, and don't let Heather boss you. I hope the enclosed will help. Best wishes to all. Love, Aunt Nell

Margaret twisted the ring on her finger, listening to the sound of her blood beating in her head. She looked at the folded check: a square of beige on her bedspread. If she never unfolded it she would never know. She would never have to do anything, ever. She could sit in her parents' house with the check unfolded for the rest of her life. The check would yellow and crumble and disintegrate, her sweatpants would fuse to her legs, she would go blind from reading, she would eat tortellini and ice cream until she croaked. They would have to cut Great-Aunt Peggy's enamel ring off her fat finger.

She touched the check-poked it, hoping it would unfold by itself and reveal its magic. It could be anything-twenty dollars toward her ticket, a hundred.Hope the enclosed will help. Aunt Nell was selling the old house and moving to a condo: did that mean she'd be feeling rich or poor? What didhelp mean? Margaret in blue ink with a flourish? A cache of worthless jewelry?

She began to think she was incapable of unfolding the check. She would have to take it to someone and get them to do it for her. Mrs. Niedermeier next door. The man at the bank. She twisted the ring around her finger. souvenir of cold springs. How strange that the ring fit her so perfectly. Was that a sign? A sign of what?

She picked up the check and held it for a moment without unfolding it, thinking: this is absurd, you are pathetic, if it's not enough what will you do, what will you do, you'll call Roddie, you'll go to Brown, you'll go back to Harvard and eat dirt, you'll go mad, you'll die, you'll die, you'll die. Oh you melodramatic jerk. Stop it, stop it. Her stomach churned. She closed her eyes, unfolded the check, opened them.

It was a check for a thousand dollars. She put her head in her hands and cried for the first time since Emerson. She felt her heart begin to unfreeze. The ice melted in her veins. She would live.

Excerpted from Souvenir of Cold Springs © Copyright 2003 by Kitty Burns Florey. Reprinted with permission by Berkley, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. All rights reserved.

Souvenir of Cold Springs

- paperback: 336 pages

- Publisher: Berkley Trade

- ISBN-10: 042518840X

- ISBN-13: 9780425188408