Excerpt

Excerpt

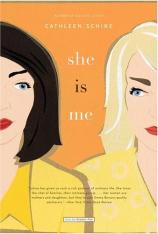

She Is Me

one

Motherless children have a hard time, but what about the rest of us? Elizabeth thought. Motherless children have a hard time, when your mother is dead....She must have sung out loud because her mother, Greta, slapped her hand lightly and said, "That's enough music."

Elizabeth put her arms around her mother. "Thank you for coming," Greta whispered. "You're a good daughter. "Tears appeared below the rims of Greta's sunglasses and ran down her cheeks.

"Mom, she'll be okay," Elizabeth said. "Don't cry. You're a good daughter, too."

Then Elizabeth began to cry. And wished she had sunglasses. "It's so fucking hot in here," Greta said, patting Elizabeth's back in an almost unconscious, ritualistic gesture of comfort. "Why do they have the heat on? They'll make us all sick. "She turned to the doctor's receptionist. "First, do no harm!" she said. The receptionist, a middle-aged black woman with long, squared-off plastic fingernails, looked up.

"Maybe you're having hot flashes," Elizabeth said. She wiped sweat off her forehead with the back of her hand. "Maybe we're all having hot flashes."

The clacking of the receptionist's manicure on the computer keys resumed.

Elizabeth listened to the pitter-patter of plastic against plastic, the rhythm of work. Order. A peaceful resolve. One foot in front of the other. One fingernail in front of the other.

She imagined her grandmother's skin. Her grandmother was so proud of her skin. It was white, as white as the shoulders of a heroine in a novel. It was soft and scented by Ponds cold cream. How many times had that cheek been presented to her to kiss? How many times had she seen it approaching, in the slow motion of a horror movie? Once, she ran away from the advancing cheek, and her grandmother cried. When Elizabeth got older, she loved to kiss her grandmother, loved the old-fashioned delicacy of her face. But as a child she'd sometimes felt suffocated by her grandmother's cheek, by her strong, grasping fingers, by the demand. Elizabeth did not like demands. Unless it was she who made them.

"Poor Grandma," she said. She shed a few tears. Then stopped herself. Then sniffed.

Her mother stood up. She took several tissues from a box on the receptionist's desk. "Here." "Filthy tumor," her grandmother had said when they'd found out. "Why couldn't I have it on my goddamned ass?" Elizabeth blew her nose. She wiped the back of her neck with another tissue. She sat in the waiting room, sweating, a dirty tissue in each hand.

Now, Lotte, shut up, Lotte said to herself. You son of a bitch, you've had a good life. And there's life in the old mare, yet. She adjusted her hat, patted her hair. Beautiful hair with a natural wave. The haircutter came to her now. Fifteen dollars, that was all, no charge for the house call. Of course, she gave him a big tip. He was a darling, and so devoted to her. Well, that's just the kind of person I am, she thought.

Her daughter, Greta, was talking to the doctor. Handsome? Like a matinee idol. But such a waste on such a cold, cold fish. A top man, of course, world renowned, best in his field, with that flashlight, like a miner, on his forehead. Two assistants to go through before you could speak to him, and then he was abrupt, rude, let's be frank, all they wanted was money. Butchers. Even so, this gorgeous stiff with a pole up his high-priced ass had stayed to talk to her, had laughed at her joke, had called her by her first name and told her she was as sharp as a tack.

"What about chemotherapy?" Greta was saying. Greta wore ridiculous clothes for a grown woman. She wasn't at all bad looking, and she'd never put that weight back on, God bless her. But Greta neglected herself. Lotte wondered how she, Lotte Franke, née Levinson, practically brought up in Levinson's, her family's department store, how she, an actress-a dancer, anyway, and on Broadway, don't forget-how she had raised a daughter who could appear in public in such dreary clothes.

"You're dressed for the rodeo," Lotte said in the car on the way home.

In the backseat, Elizabeth laughed. "Grandma, have you ever seen a rodeo? I mean, how would you even know?" "I'm wearing jeans, for heaven's sake," Greta said. "Not chaps. "Lotte began to cry. "I don't want a hole in my face." "Grandma, Grandma, they cover the hole," Elizabeth said. She took Greta's shoulder. "Don't they?"

"Plastic surgery," Greta said. "And they're blue jeans, Mother, just like everyone else on earth."

"You see?" said Elizabeth. "Plastic surgery. Like a movie star. "Elizabeth was a wonderful girl. Subdued, but chic. If she would just let her hair loose, instead of pulling it back like a librarian. "Beautiful, wavy..." Lotte said, clucking disapproval. "We did go to a rodeo once," Greta said. "Remember, Mother? Lake George? It was so hot Daddy drove in his boxer shorts?" "My Morris," Lotte said with a sigh. What a nightmare that trip was. And the filth!" You've got real style," she added, turning to Elizabeth. "That's genetic."

A little makeup would be nice, too, though. Spruce things up a bit. Too serious, these young people. Working so hard. They all looked haggard.

"If it's so genetic, what the hell happened to me?" said Greta. "You," Lotte said. She raised her shoulders in a shrug. "For the rodeo, you're not bad." She suddenly lifted both her large, bony hands. She clasped them together as if in prayer. Her bracelets clattered. "What would I do without you?" she said. "Without you two? My family. My family..." She trailed off. Leaned her head back. She was so tired. They were going to cut up her face. She might as well take the pipe.

Her face. Her beautiful skin that everyone admired. All her life they had admired her soft, white skin. Never even a pimple. She sat up straighter, gazed down at her wedding ring, not the original simple band, but a thick tire of gold studded with diamonds. Now, stop your moping, Lotte.

Life can be delish with a sunny disposish....She ran the old song through her head, tried to smile. She'd done it at the Roxy. Or was it the Orpheum? She could hear the sound of her shoes on the stage, the chalky dust that rose like little clouds and settled on the black patent leather. A sunny disposish. But she was so tired. Couldn't she just die and be done with it? It was about time, anyway. She was old. It would be so much easier. For Greta. For Elizabeth. For all of them.

"But I'm just not ready yet," she said, only half to herself.

The 405 goes north and south, the 10 goes east and west. Elizabeth chanted these words in a silent singsong.

So, I take the 10. No, no. The 405. Take it through the pass that takes you over the hill and into the Valley to the 134, which turns into the 101....There was something unnerving about driving somewhere new in L.A. Everyone kept a map in the car, even people who had lived their entire lives in the place. Elizabeth had not lived her entire life in Los Angeles. She had learned to drive on the North Shore of Long Island, where she had grown up. She still felt the ocean was placed all wrong in California. Go west, someone would say, but you couldn't even follow the setting sun if the sun happened to be setting, because no one meant "west," really. They meant toward the Pacific Ocean, and the shore jutted out in peninsulas or formed bays, or did whatever else it could think of to make "west" mean something that had absolutely nothing to do with the location of the long white beach and the crashing surf. When she had first started driving in L.A., she'd gotten herself a compass, but a compass was useless in this strange land.

"And the women!" her grandmother had said, when Elizabeth told her how strange L.A. felt. "With their tztizkes hanging out!" She squinted in the glare of the beautiful sun. Yellow flowers that looked like a child's crayon drawing lined the freeway. She got off at the correct exit. She held the directions she had downloaded from the Internet and tried to follow them.

After 1/8 of a mile, turn left. Continue for 1/3 mile. Take second right.

The instructions were overly detailed, confusing and uninteresting at the same time. That was the definition of a boring person. But Elizabeth was not bored. She was frantic. And how much was one-third of a mile added to one-eighth of a mile? She arrived in plenty of time. But she was worn out, her underarms damp, her head throbbing. And she had to pee. She didn't really understand why she was here. Why she had been summoned. She couldn't compete with women who had tztizkes hanging out.

She found the correct gate on the third try. A uniformed man came out of a glass booth.

Elizabeth said, "Elizabeth Bernard for-" "He's expecting you," said Greta the attendant. A concierge in a brass-buttoned blazer took her in a small elevator paneled with exotic wood to a large waiting room paneled with exotic wood.

"Eliz-" "He's expecting you," said Greta the receptionist at the first desk. "He'll be a few minutes late," said Greta a second receptionist. "He apologizes," said Greta the first.

Maybe I can just have the meeting with these two, Elizabeth thought. They were both purposefully unglamorous, she noticed. She forgot about peeing. She sat in a chair and looked out the windows at a flowering tree. The waiting room was historic, she knew. The style of the studio boss who ruled here in the 1930s had been left intact. Towering silver doors etched with art deco designs. Crystal statuettes. Curving, undulating wood. Why am I here? she wondered again. I don't belong here. I belong in a cramped office correcting papers about the Lacanian implications of How to Marry a Millionaire.

The silver portals swung open.

"Come in!" said a man in a suit and tie, the first man in a suit and tie Elizabeth had seen in the week she'd been in L.A. He was waving her in, grinning, excited.

She followed Larry Volfmann down three steps into an office as soft as a thigh-carpeted, upholstered, and pillowed. Larry Volfmann is a millionaire, she thought. What would be the Lacanian implications of marrying him? "How's your trip? You like L.A.? First time out here? Takes some getting used to..."

He talked so fast it was difficult for Elizabeth to convey that her parents had lived in L.A. for years, had moved there when she was in college.

"...started out as a bunch of Indian villages, then towns, now they're all linked together, so, you know, it feels like it has no center because it actually has no center..."

Elizabeth wondered again what she was doing there, summoned before this great man. She had heard that all powerful men in Hollywood were short and was a little disappointed to see he was actually of average height. He didn't have a tan, either. Or wear a baseball cap.

"Mr. Volfmann-" "Larry..." He handed her a bottle of water. "Larry, it's so good to meet you. I'm a little stunned, of course-"

"Happiness," Larry said, interrupting. "Passion. "He waved a magazine at her. "Intoxication. "The magazine was Tikkun, the issue with her article about Madame Bovary. "Happiness, passion, intoxication. I like it!" He shrugged as if to say, I like happiness:sue me! "I like it," he said again, tapping the page. "Well, those are Flaubert's words," she said. She smiled, modestly, she hoped. "Not mine."

And don't think you can con me or co-opt me or impress me, either, just because I'm a dreary academic, just because I'm impressed that you somehow manage to read Tikkun. I don't read Tikkun. Who has time to read anything? And you probably have even less time than I do, although I bet you don't have to run home after work and make dinner and play with Brios and Duplos and Play-Doh. Maybe an assistant read it. No. What assistant would have the balls to recommend an academic article in a down-at-the-heels Jewish monthly? This has to have come from the eccentric boss himself.

"No," Larry said. "Not Flaubert's words. Emma's words. "Surprised, Elizabeth examined the eccentric boss himself. He looked a little like a boxer-the dog, not the athlete. Dark eyes, a bit jowly, but fierce. High-strung. And he was right. Happiness. Passion. Intoxication. They were Madame Bovary's words, the words Emma Bovary read in books, over and over.

"The words her marriage failed to make her understand. They're Emma's soul, her quest, her destiny, her tragedy..." He was still waving the magazine around.

Elizabeth smiled. A man of business, as Larry Volfmann so clearly was, was discussing her humble article. As she smiled, her pleasure at being noticed by him transformed almost effortlessly into a warm sense of personal superiority. Okay. I get it, she thought. You're smart, you're serious. You went to college. You're sensitive. You studied literature. But somehow, life took a funny turn and here you are, a man with a literary mind stuck doing action movies at Pole Star Pictures. The head of Pole Star Pictures, who earns more in one week than I earn in a year, but you haven't given up your soul....She continued to smile at him and nodded to convey thoughtful attention the way she had learned to do with ardent students. He tilted his head, as if he'd been petted. She wondered if he was muscular like Fritz, the boxer dog who lived on the third floor in her building in New York. He was a little bowlegged, she had noticed. Like Fritz. And, to be fair, he might make a lot of money and be driven in a limousine, but he was right.

Emma Bovary was so fucking compelling. It didn't matter how obvious one's response was, how banal, how romantic, how innocent. All of that just somehow made Madame Bovary-so compelling in her own romantic, innocent banality-all the more compelling.

"'The Way Madame Bovary Lives Now:Tragedy, Farce, and Cliché in the Age of Ikea, '"he read. "We'll have to change the title, of course."

She stared at him, speechless, until he began to laugh and she realized he was making a joke. "It's tough," he said. "I mean, it will be tough to make it fresh.

Because, you know, every movie is really Madame Bovary, right? Madame Bovary'R'Us!" He laughed. He was having fun. The phone rang.

"What?" he answered, tough and rude, just like an executive ought to be. "If you could remove your tongue from my ass and say whatever it is you want to say...Uh huh...Right. Do it! I like it!" He slammed the phone down, put both elbows on the desk and his chin in his hands, and stared expectantly at Elizabeth. "So...sort of like Clueless meets American Beauty?" she said.

After all, he was offering her cash money, and quite a bit of it. "Don't patronize me, Professor Smarty-Pants," he said. "I don't know if you can write a script even half as good as either of those. I don't know if you can write a script at all, do I? I'm going out on a limb for you-" "No, I just meant-"

"I know what you meant, I know what you meant," he said, leaning across the desk at her, almost lying on it. He moved one hand, as if waving away smoke. "History. Ancient. Gone....I'm not looking to you to marry two pictures we already saw. No marriages, honey. I want...adultery!"

"I just-"

"I want new! I want to stray, roam, betray the conventions. And find me..."

He paused. Slowly, seriously, he said, "Find me Emma Bovary." Elizabeth felt the cold beads of water on the Evian bottle. When students assaulted her with their enthusiasm, she learned to watch them and nod while trying to decipher their barrage of critical theory and undergraduate sentimentality. But this growling man was not a student. His enthusiasm was not youthful. Critical theory was not a phase he would eventually have to grow out of. And she was not his teacher.

Elizabeth took her wet hand from the Evian bottle and put it on her forehead. I really want to do this, she thought, surprised. And she suddenly very much wanted to please Mr. Larry Volfmann, too.

"Familiar but fresh," he said. "Fresh." "But familiar." "But..." She hesitated. "Fresh?" "No. I mean, yes. But..." Volfmann glared at her. "But what?" "But I'm an academic." "You'll get over it. Look," he said, pushing Tikkun at her, "I have a feeling about this. Trust me. "And I don't even have tenure, she thought.

"I've always dreamed of doing this project, but how the hell do you update Madame Bovary when every picture with an unhappy young wife is Madame Bovary?" "I don't know," Elizabeth said.

"Then, I'm in the gym," he said, paying no attention, "and I'm reading, and...here it is!" He smacked the magazine. "Concept. Clarity. Class. "He smiled at her, his boxer jowls lifting. "You've got the common touch."

I certainly do not, Elizabeth wanted to cry out, offended. "In spite of yourself," he added. "Oh. Thank you," she said.

Larry Volfmann leaned back, his hands behind his head. He spun around, 360 degrees, in his leather chair. "You on?" he said.

"Well, but, I don't really have any experience..." Shut up, asshole, she told herself. Way to talk yourself out of a shower of fucking riches.

"No. But you've got..." He thought for a moment. "Seychel," he said. "You know what that means?" She nodded. But he continued anyway. "Common sense. I mean, that's the translation. Good, common sense."

"Yeah. That's good," Elizabeth said. "Yeah. I like that." "Seychel," he said.

"Thank you," Elizabeth said. She realized she liked him, even though he had read her paper on Flaubert in Tikkun and wanted to pay her a lot of money to write a screenplay for an updated Madame Bovary, to turn poor Madame Bovary into a "project. "She liked him even though he was buying Emma Bovary as if she were a new sweater, cashmere, but still;and buying her, Elizabeth, as if she were...what?

Oh, come on, now. You mean you like him because he's buying you. Don't be a prig about selling out, you prig. "It's oddly comforting to be a commodity," she said. "Back at you," he said.

Greta remembered when Elizabeth was a baby, her beloved first child. When she woke up in the morning, her first thought had always been of little Elizabeth. To call it the first thought was not quite accurate, though. It was the continuation of last night's thought, which was a continuation of that day's thought, which was simply a continuation of the thought of the day before.

Elizabeth had filled Greta's consciousness. She was a beautiful baby with intense, dark eyes and, even then, a worried scowl that could burst into a smile so unexpected and bright it caused complete strangers to laugh out loud. Elizabeth's eyes were still big and dark and round. She stilled scowled, too often for a grown woman. But she smiled, too, and when her big, wide smile appeared, it still broke through like a glorious surprise. Elizabeth's whole face lifted into an expression of such benign, open joy that those around her knew the world was good and fair and our reward would come in this life;we would not have to wait for the next. Witnessing the transformation from pensive baby moodiness to generous baby joy had felt like a gift. It had always been Elizabeth's unconscious, secret power. It still was. When she'd left the house earlier to go to this mysterious meeting of hers, she had turned her head just before the front door closed and the smile had been revealed and the people, or Greta, who was the only one present, had rejoiced.

Greta had existed in the baby's beauty, in her moods, in her needs. Now, she realized, she existed in Lotte in the same way.

Her mother's comfort, her spirits and moods, her demands, and her sad, vulnerable needs had been transformed into the air she breathed, a steamy atmosphere as real as the mist that poured from Lotte's humidifier, which Greta was careful to clean every day.

Lotte's voice had wormed its way into Greta's head. Lotte's pain was as clear to Greta as if she felt it herself. The disappointment Lotte felt with each failed treatment, each unsuccessful doctor's appointment, weighed heavily on Greta's chest. Lotte's joy, the intermittent, glorious moments when she struggled up from her illness and courageously enjoyed a new pair of shoes, a huge, garish sunflower, or a cookie-this was Greta's joy.

"It's like having a two-year-old," she said to her husband. But how could Tony know what she meant?

"You have to separate yourself from her a little bit," he suggested.

Greta looked at him, disturbed. Separate? "Why is that a goal, I wonder?" she said. "I know it is. I know it's what we're always supposed to be doing, all our lives. The therapists so rule. But why?" "Self-preservation?"

Preservation? Should she zip herself up in a plastic Ziploc bag and preserve herself in the vegetable bin in the refrigerator? Even though she wasn't the one whose face was rotting?" Don't you think'self-preservation'is just a nice contemporary phrase for selfishness?" she said.

"No," Tony said. "I don't. People need boundaries. "She hated the way he said "boundaries. "It sounded as though it should be written with a capital B. Tony often seemed to capitalize his nouns.

"People need Boundaries," he said again. Perhaps People do, she thought. Tony would know. He was an authority on People. He looked authoritative, too, standing there, his rather large head with its pleasantly crow-footed blue eyes and firm, reassuring, smiling lips.

"Fuck people," she said. Elizabeth walked out of Larry Volfmann's office still gripping her bottle of water, now empty, now warm. Most people thought Elizabeth willful, but she often felt her will was not entirely her own. She was a person who appeared arrogant and unmovable not because she made up her mind and then stuck to it but because she found it so difficult to make up her mind to anything at all. Elizabeth waited, and waited, and waited, hoping for that elusive bit of evidence that would finally and utterly convince her.

Sometimes there was no alternative before her, and then she would rush down a path as if pulled by gravity. It made people think she was ambitious and energetic. But I'm passive, don't you see? That's why I studied so hard in school-too lazy not to. And now this. I'll do this because Larry Volfmann told me to.

"Elizabeth?" Elizabeth realized she was still standing in the waiting room with her empty plastic water bottle. A young man stood in front of her, short, preternaturally tanned, his thinning blond hair gelled into alarming spikes.

"I'm glad I caught you," he said. Elizabeth was not glad, somehow, although she did feel caught. "I'm Elliot. "He took her by the elbow and led her to another office. "Elliot King."

"Look," said Greta Elliot King. "I'm sorry. "He sat at his desk and put his feet up, motioning her to a chair. "I'm just a businessman," he said. Elizabeth sat and looked past the soles of his Adidas at the businessman who was sorry. His brows were knit. He put a pencil to his lips.

"I have to warn you about Larry," he said. "You do?" "I love him dearly," he said. Elizabeth nodded. "He's the boss," he said. She nodded again. "The studio head." "Right."

"I love him dearly. "Elliot stared at her. "But I'm just a businessman. "He threw the pencil onto the table, where it skipped like a stone. "Elizabeth Bernard," he continued, "your head is spinning, right?"

She nodded. "Heady stuff, movies," he said. "Like champagne, right? You want to be in the business, right? Because it is a business. A business you want to be in. But who doesn't? Every kid wants to be in the entertainment industry. But let me tell you something. "He leaned back so far that Elizabeth could see into his nostrils. "As a businessman. As the man who picks up the pieces. "He snapped his head forward and stared at Elizabeth with obvious hostility. "Madame Bovary?" he said. "Who are we kidding?"

Elizabeth did not know what to say. Was this planned? A loyalty test? She shrugged, hoping that did not commit her either way. "Elizabeth, Elizabeth, the man is sincere, don't get me wrong. I love him dearly."

Elliot's phone rang. He picked up the receiver, motioning for her to wait. He nodded, grunted once or twice. "The murders are boring, I told you that," he said.

Elizabeth tried to look intelligent and interested and comfortable, but she was hot with embarrassment. "I love you dearly, you fuck. Just give me a cooler murder, maestro."

He hung up. "Business," he said apologetically. Elizabeth shifted. She was having trouble focusing on Elliot. She had not eaten and she was feeling faint and far away. She felt her belly was sticking out and wished she had not worn this shirt. She wondered if she would ever find her way home.

"I know this industry," he said. "I know the marketplace. I know your patron, too, Professor. I love him dearly, but the man is like a dog with a bone when he gets these'literary'ideas, gnawing and slobbering all over them and then, what? Drops them in the dirt. Look, I'm just a businessman, but, whim or no whim, Larry Volfmann is a businessman, too, and movies are a business, and bad business is bad business. And Madame Bovary...who I love dearly, by the way..."

He held his palms out. "You get my point?" Elizabeth said, "I'm a little confused, actually." "Need I say more?"

Greta was on her knees weeding when Elizabeth got home. Her daughter did not look sunny anymore. Greta stood up. "How was Mr. Wolfman?" "Volfmann." "Wolfman, Volfmann...Did you hit traffic?"

She put her hand on Elizabeth's cheek, leaving a smudge of dark, rich dirt, and wondered if this tall grown woman dressed in black who drove a car and plucked her eyebrows could really be her daughter, her little whining Elizabeth, her baby. "Mom..."

Yes, she decided as Elizabeth wrinkled her face in an unattractive, hostile way. She could. "Mom, I got a job. Then this asshole told me not to take it-" "Volfmann?"

"No. The other one. Elliot King?" "Oh! His mother is my client!" "So that settled it-"

"His mother wanted a waterfall, totally wrong for the space, but I must admit the pergola really does look great-" "So, I need an agent," Elizabeth said. "I'm supposed to write a screenplay. "Then she smiled.

Greta was suddenly elated, and wondered, not for the first time, that the moods of her children were such powerful masters, causing her own moods to do their bidding so readily. She felt herself about to clap her hands in a show of excitement as she had done when Elizabeth was a child, but caught herself and pulled back before any damage was done. Elizabeth did not like being "infantilized," as she put it.

"I'm so proud of you, darling," Greta said, instead. "God, you don't seem very excited," Elizabeth said, and headed for the kitchen, pouting.

Greta followed. Her son, Josh, now off in Alaska on a geological dig, had always been less talkative than Elizabeth, but his feelings were easier to read. Josh had been a cheerful boy, boisterous as a child, usually outside running or digging holes like a dog. Sometimes, he would come to his mother and say in a plaintive voice, with no explanation, "It's ridiculous." That's how she knew he was unhappy. It was a simple, direct communication, and she could then go about solving the problem. But Elizabeth had never been direct. Greta sometimes thought of her daughter as a ski slope in the Olympics, the ones full of moguls and poles with shimmering orange flags.

"Anyway," Elizabeth said, sitting at the table, "I'm suddenly a screenwriter. Can you believe it? I've been anointed. I've been plucked from the toilers of the academic field to write a movie. Every undergraduate's dream. It's bizarre. The guy is serious though and I kind of liked him, even if I'm just a whim..." Greta watched the clouds gather over Elizabeth's mood. "...which I suppose I have to admit I am."

And Elizabeth's eyes narrowed. Then she sighed. Then she put her head down on the table. Then she picked her head up and looked at the ceiling.

"Elizabeth..." "Oh, you don't understand. "Greta looked at her daughter's neck, the curve of it as Elizabeth gazed miserably at the ceiling, her whole posture a relic, perfectly preserved, of long ago, before every spelling test, every paper or exam. Elizabeth had been an absurdly earnest and conscientious student. My poor baby, Greta thought, and, she couldn't help it, she smiled.

Elizabeth caught the smile from the corner of her eye and her scowl focused on Greta. "It's not that big a deal, Mom, okay?" "Don't be such an ass," Greta said.

" he said it was his pet project," Elizabeth said. "People abandon pets. He'll send his limo to dump me and Madame Bovary by the side of the road. Or have his assistant drown us in a burlap bag. Then he'll buy himself some goldfish. "She stood up and opened the refrigerator.

"Just enjoy the moment, darling," Greta said. Elizabeth gave her a savage look. "Lots of brilliant people come to Hollywood and fail. "She took an apple from the fridge and riffled through a newspaper that lay on the counter. The phone rang beside Elizabeth's elbow, but she seemed not to notice. "Like, say, Bertolt Brecht," she said.

"Goldfish," Greta said. "God, that reminds me. I have to get koi for that Ripley woman's fish pond. "She reached past Elizabeth, picked up the phone, and heard her mother's voice, irate, no "hello."

"I can't get this screwy machine to work," Lotte said. "Brilliant people," Elizabeth was saying, ducking under the curling telephone cord, throwing herself down on a kitchen chair and biting her nails. "And I'm not brilliant..." "Goddamnit, everything is so complicated, they used to give you a switch. One switch. It went up, it went down..."

"Mama," Greta said into the phone, "what machine?" "It went on, it went off..." "The TV? The dishwasher?" "...or coming to Hollywood," Elizabeth said. "Fine," Greta said, turning to Elizabeth. "Fail from New York!

Who cares?...What machine?" she said again into the phone. "Don't use that tone of voice with me," Lotte said. "I may be old, but I'm still your mother..."

"You're so supportive," Elizabeth said, pacing up and down the kitchen.

"Stop regressing!" Greta yelled at Elizabeth's back. "And don't you start with me," she added, into the phone.

Lotte began to cry. It was a terrible sound, high and unearthly and somehow unclean and unnatural, too, the howl of the wind on a moonless night, a bird of prey plummeting to its death, a wolf caught, squeezed without mercy by its bloodthirsty throat. Greta had heard it all her life, and she had never gotten used to it. It frightened and enraged her. It turned her stomach with terror and murderous rage. She dreaded that weeping, as exaggerated as Lucy Ricardo's, as loud as thunder, as eery as lightning.

"Mother, please, don't..." "All the machi es, the buttons..."Lotte was wailing. "My own flesh and blood...It's inhuman, Hitler should have had to push so ma y buttons..."

"What machine?" Greta said again, very calmly, very slowly, as she watched Elizabeth sit down again. Your mother is very old, she told herself. Very very old. Pretend she is a child. Just like your child, your highly competent, adult, big horse of a child sitting at the kitchen table biting her fingernails and spitting them on the floor. "Stop that!" she said to Elizabeth. No, no. Patient. Be patient with your child, as if she were a child. Be patient with your mother, as if she were a child. "Which machine is bothering you, Mama?" "What?" Lotte said, the crying over, her voice back to normal. "For God's sake, darling . I've got it. I'm not senile."

Elizabeth went with her mother that afternoon to pick up Lotte for another doctor's appointment. In the face of death, she thought as they waited with Lotte in the examining room, what difference did it make if you wrote a screenplay? If a tenure was on track or not? If your three-year-old slept in your bed and you really didn't mind?

"Ultimately everything is meaningless," Elizabeth said. "Don't be maudlin," her mother said. "What?" said Lotte. "What did she say?" "Nothing," said Greta Elizabeth. "Nothing," said Greta.

Lotte sat on the examining table. Elizabeth was leaning against the door. She felt it push against her and she stood back to let the doctor in. This was the third doctor they'd tried since she'd been in L.A.

"Well! Mrs. Franke!" said the doctor, yet another broad, tanned, unsmiling specialist with his headlight strapped to his forehead and a pair of reading glasses balanced on his nose. Her grandmother looked white and bony beneath the blue paper gown. It crinkled noisily as she held out her arms, then surrendered to the metallic burst of Lotte's bracelets. "You're handsome," she said, shaking her finger at him, "for a butcher!" The doctor smiled a thin smile. He began to examine the red spot by her left nostril.

"Does this hurt?" "Hitler should have my pain. "He poked some more. "The gangster," she said. "Never even had a pimple," she added. "Who? Hitler?"

"That dirty son of a bitch," she said. "Me," she said finally when the doctor made no further response. "Me. I never had a pimple in my life. Not one. Look at this skin." "That's what I'm doing, Mrs. Franke." "Call me Lotte," Lotte said. "Loosen up, Doc," Lotte said. "Cheer up, what are you, Dr. Karoglian?" she said. "Kevorkian," Elizabeth said.

The doctor, who had studiously been ignoring everything but his patient's tumor, turned to Greta and said, "Your mother is a pistol." "Aha!" Lotte said. She smiled triumphantly. "You, Dr. Whatever- Your-Name-Is, said a mouthful."

It was almost six by the time they got home. Elizabeth clumped up the stone steps into her parents'house, a three-bears, wood-shingled sort of place nestled into a hill in the Rustic Canyon section of Santa Monica. Greta's elaborately designed garden billowed around Elizabeth as she climbed the steps and navigated the mossy path that led to the front door. Her mother designed gardens for a living, and her own garden, changing styles every few years, was now a carefully planned jumble of roses and heather and lavender. "Through the moors and highlands, fells and dales, the downs, the heaths, the copses..." Elizabeth said.

"Such a vocabulary," said Greta Grandma Lotte proudly. Elizabeth left them and went out to the patio in the back. There were more steps, leading up the almost vertical hillside to the pool, and she heard Brett and Harry splashing and playing up there. Daffodils swayed in the breeze, hundreds of them. She was a little homesick for New York, there at Santa-Monica-on-Thames. The daffodils reminded her of springtime in Sands Point, Long Island, where she had grown up. But the smells were off. It still smelled so strange to her at her parents'California house, even though they'd lived there for more than ten years. Like an exotic desert spice cabinet, in spite of every British blossom her mother planted. The smell of one particular flower-she hadn't been able to locate the culprit yet-intruded now and then, a nauseous scent, like dog shit, wet dog shit, waiting to jump her when she least expected it. She heard Brett coming down the stairs, singing "Yankee Doodle "to Harry.

"I'm a foreigner here," she said. "Even though I grew up here. "She was sitting with her back to the stairs. She didn't get up or turn around. She liked that moment of uncertainty, not knowing exactly where they were, but knowing they were there.

"You didn't grow up here," Brett said. He was right behind her now. "Your parents moved here when you were in college. "Elizabeth felt his hand, cold and wet from the pool, on her neck. She reached back and held it. Something began tugging on her hair and Brett walked into view, holding Harry, whose hair was slicked to his head, his face shining, his wet eyelashes even darker and longer than usual. His fist was clamped around a lock of her hair, pulling it loose from the clip.

"Let go, Harry," Brett said. "I feel like a foreigner, too, sometimes." "You are a foreigner."

Brett had grown up in South Africa. His father was an outspoken liberal there, a cancer researcher and university professor in Cape Town, and they had been forced to leave when Brett was eight. The family moved to Rochester, a cultural and climatic change that was reflected in Brett's accent, which shifted from the soft, sweetly off-kilter British accent of English-speaking South Africa to the flat, nasal tones of upstate New York, depending on which word he had learned in which place.

He had been Elizabeth's student, which was how she met him. Brett stood out from the other students not only because of his height but because he was so obviously older, a couple of years older than Elizabeth. His hair flopped down from a middle part and he kept jerking his head to the side, like a teenage girl, trying to get it out of his eyes. He'd had a goatee then, too, and had looked wonderfully poetic to Elizabeth. Even so, there was no reason for him to be attending a seminar called The Poetics of Adultery. He'd already gone through law school and worked for a year at a firm in New York when he decided to go back to school to get a graduate degree in philosophy. Elizabeth met him outside her classroom, where he sat on the floor, a disturbed look on his face, listening to a squawky news broadcast on a small radio.

"My father's uranium has been stolen!" he said, pointing at the radio.

Brett was not like anyone she'd ever met. His career was upside down. His accent was motley. His father's uranium had been stolen. He wore a gray checked shirt and a pale-blue plaid tie. He had a long face and a narrow, prominent nose. His eyes were narrow, too, and dark. But his mouth, which was wide, and two deep dimples softened the sharpness and gave him a demeanor of distracted gentleness. Elizabeth fell instantly in love.

"Why are you taking my class, anyway?" she asked him some months into the relationship. "It's not required. It's not related to what you're doing. It's not even a graduate course. "She realized as she asked the question that she hoped he would say he had seen her, admired her from afar, and registered for the course in order to get to know her.

"Well, it's so early in the morning, your class. So it seemed prudent, didn't it?"

"It did?" Elizabeth said.

"In a getting-oneself-out-of-bed sort of way." "But now you've got yourself into bed," Elizabeth said, indicating the rumpled sheets and pillows around them. "Yes," Brett said. "It all came out right in the end." Elizabeth remembered that day so well. Brett had suggested they get married. He had often suggested it since. And just as often she had suggested they wait.

"Let go, lightey," Brett said now to Harry. "You'll hurt Mommy." Harry was shaking his head no. How did Harry know that what sounded like "lit go "when Brett said it had the same meaning as "let go "when Elizabeth said it? How the hell did he know what "lightey "meant? Children were very intelligent. He was three, skinny for a toddler, which she liked, though before he was born she admired only stocky, sturdy toddlers. She reached for him and stood him on her lap, wondering at the almost desperate surge of love, as if they had been apart for forty years rather than forty minutes. "Brett," she said, pronouncing it "Brit."

Brett hated his name. "Shut up, won't you?" he said. Elizabeth asked Harry if he needed to pee. He glared at her.

"Should we call Daddy'Bob'?" she said. Harry shook his head. He smiled from behind his pacifier. He pulled the pacifier out with a pop. "No," he said. He plugged himself up again.

Elizabeth put her face against his cool forehead. She rather liked "Brett." A cowboy name. Harry's hair stuck to her lips. She drew in the damp scent of his little body, felt his curled hand pushed against her breast. She listened to him breathe. She closed her eyes. She heard the birds, the dogs barking next door. She felt the cool air. God, she thought. There is a God after all. "Don't cry, Mama," said Greta a small voice.

Elizabeth opened her eyes. "Sad?" he said. He offered her his pacifier.

"No, no." She wiped her eyes. "Mommy's having an epiphany." When Greta came out and saw little Harry curled in Elizabeth's lap sucking on his pacifier, she thought how cute he looked, his cheek creased against his mother, his wet hair stuck to his forehead. His swim diaper was swollen with pool water. She suddenly remembered the soggy weight of Elizabeth's postnap diaper and the threatening furrow of her brow, like a dark storm cloud on the horizon.

Greta kissed Elizabeth on top of her head and pulled playfully at Harry's pacifier, as if it were the plug in the bathtub.

"It doesn't hurt their teeth," Elizabeth said. "I haven't said a word." "Good. Don't."

"Look at you, Elizabeth! You're curling your lip the way you used to when you were little," Greta said. She smiled at the memory, which for some reason comforted her. "I think pacifiers are cute, if you really want to know," she said. "Like Maggie Simpson." "That's hardly the point," Elizabeth said.

"No, that's hardly the point." Greta sat across from Elizabeth and Harry. Harry reached out for her, then crawled wordlessly across the low wooden table between them and settled in Greta's lap. Greta held him and remembered Elizabeth as a child so clearly it was confusing. Elizabeth's curly brown hair, her mouth round and talking at full speed or silent and extended in a determined pout, her manner ridiculously arrogant, her cheeks pink and vulnerable. "What are we going to do?" Elizabeth said, tears coming to her eyes. "I feel so helpless." She reached across the table and took her mother's hand.

Such an unlikely combination, Greta thought. The misanthropic sentimentalist. Skeptical of the world at large, Elizabeth could nevertheless be foolishly, innocently, and thoroughly zealous toward the world up close. It struck Greta, not for the first time, that Elizabeth was a sort of inside-out version of her father. Tony was an exceptionally kind person, though it was necessary that the objects of his kindness be generalized, categorized, and named as part of some group, like "the Elderly" rather than his parents, or "Empty Nester "instead of his wife, or even "Awkward Adolescent "when that term fit Elizabeth and Josh. Groups of complete strangers were, of course, ideal. Tony had briefly succumbed to the lure of Mao in college, and he still retained a great compassion for and interest in the needs of the People. It was a shame, Greta thought, that he was so vague about any person in particular. Elizabeth, on the other hand, was as loyal as a dog to her friends and family, as wary as a dog toward the rest of the world.

"You're just like Daddy," Greta said, and Elizabeth looked so pleased that she did not have the heart to add, "in reverse." For the next six months, Elizabeth flew back and forth to Los Angeles in a frantic shuttle that accomplished nothing, never did anyone any good, and still seemed vital. She met once with a young agent who was the nephew of one of her mother's clients and willing to sign up just about anybody, but most of the monthly visits were a simple attempt to help her mother out.

Now, sitting in her own living room, a long, dark rectangle with windows facing an air shaft, she dialed her grandmother's number, sure that Greta would be there as well. She always was. It was a bright, sunny day outside, but the room was so dark that Elizabeth could barely see the toys mounded like the banks of a river along the walls. Her mother answered Grandma Lotte's phone. "Grandma's pretty good today," Greta said. "I just gave her a shower."

"A blessing, "Elizabeth heard Lotte say in the background. "What about you, Mom?" Elizabeth said. "You're exhausted." "How's Harry?"

"You can't keep running over there every five minutes, sleeping on Grandma's couch, cooking for her and for Dad...And you're working, too..."

"What am I supposed to do?" Greta said. "Grandma has to eat, she needs to shower..." Then her tone changed abruptly from a tense and defensive rumble to a tight, higher-pitched sound of controlled, straining rage. "Mother, I told you before," she was saying to Lotte, "the pills are lined up on the dining-room table. In order. Look. See? You check off the box on the pad when you've taken it....No, you will not die of liver disease because you took your Tylenol twenty minutes early...Yes, I will fix your lunch as soon as I'm off the phone with Elizabeth..."

"Mom? Hire someone?" Elizabeth said, as she always did. "Easier said than done," Greta said, as she always did." I want Jell-O," Grandma said. "It's like having a two-year-old," Greta said into the phone to Elizabeth.

"I'm three," Harry said. He had picked up the extension in the bedroom.

"Yes. You're Grandma's big, good boy. "Elizabeth was glad she could bestow solace in the form of Harry, because her mother would accept little else. Whenever Elizabeth went out there, she of course took Harry with her. Greta was so happy to see him that she seemed to cling to him, pressing her cheek against his head the way she still did with Elizabeth sometimes, so perhaps the trips really were restorative in some way. Her mother was not feeling well, rushing to the bathroom every minute with nervous diarrhea, but when Elizabeth offered to take Grandma to the doctor or to spend a night with her or to cook her a special dinner, or even to heat up a can of soup for her, Greta would agree gratefully, then insist on coming along and doing it all herself. "Poor Elizabeth," she would say, doing all the work Elizabeth was supposed to take off her shoulders. "You've got Harry to look after."

"What about Brett?" Elizabeth said on one occasion when Brett had come with them.

"Yes, you've got him to look after, too." "Mom, that's not what I meant."

Excerpted from She is Me © Copyright 2004 by Cathleen Schine. Reprinted with permission by Back Bay Books, an imprint of Time Warner Bookmark. All rights reserved.

She Is Me

- paperback: 288 pages

- Publisher: Back Bay Books

- ISBN-10: 0316159425

- ISBN-13: 9780316159425