Excerpt

Excerpt

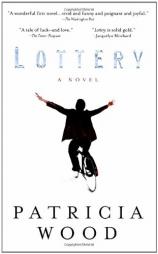

Lottery

Prologue

My name is Perry L. Crandall and I am not retarded.

Gram always told me the L stood for Lucky.

“Mister Perry Lucky Crandall, quit your bellyaching!” she would scold. “You got two good eyes, two good legs, and you’re honest as the day is long.” She always called me lucky and honest.

Being honest means you don’t know any better.

My cousin-brother John called me lucky too, but he always snickered hard after he said it.

“You sure are a lucky bastard. No high-pressure job, no mortgage, and no worries. Yeah, you’re lucky all right.” Then he would look at his wife and laugh harder. He is a lawyer.

John said lawyers get people out of trouble. Gram said lawyers get people into trouble. She ought to know. It was a lawyer who gave her the crappy advice on what to do after Gramp died.

I am thirty-two years old and I am not retarded. You have to have an IQ number less than 75 to be retarded. I read that in Reader’s Digest. I am not. Mine is 76.

“You have two good ears, Perry. Two! Count ’em!” Gram would hold my chin and cheeks between her fingers so tight that my lips would feel like a fish. She stopped doing that because of evil arthritis. Arthritis is when you have to eat Aleve or Bayer and rub Ben-Gay.

“You’re lucky,” she said. “No evil arthritis for you. You’re a lucky, lucky boy.”

I am lucky. I know this because I am not retarded.

I know this because I have two good arms.

And I know this because I won twelve million dollars in the Washington State Lottery.

1

I write so I do not forget.

“Writing helps you remember. It helps you think, Perry, and that’s a good thing,” Gram said.

“You’re only slow.” That’s what my old teacher Miss Elk said. “Just a little slow, Perry.”

The other kids had different names for me.

Moron. Idiot. Retard.

Miss Elk told them to be nice. She said I was not any of those things.

“Don’t you pay any attention to them, Perry,” Gram told me when I cried. “Those other kids are just too goddamned fast. If you want to remember, you write it down in your notebook. See . . . I’m not slow. I’m old. I have to write things down,” she said. “People treat you the same when you’re old as when you’re slow.”

Slow means you get to a place later than fast people.

Gram had me do a word a day in the dictionary since I was little.

“One word, Perry. That’s the goddamned key. One word at a time.”

Goddamned is an adjective, like, “I’ll be goddamned!” Gram will be reading something in the newspaper and it will just come out all by itself. Out of the blue. “Goddamn.” Or sometimes “Goddamned.” Or even, “Goddamn it.”

At nine, I was on page eight of our dictionary.

“Active. Change, taking part.” Reading is hard. Like riding my bike up a hill. I have to push to keep going.

“Sound it out, Perry.” Gram chews the inside of her lip when she concentrates.

“Squiggle vooollll . . . caaaa . . . nooo . . .” It takes me a long time to figure out that word.

“That squiggle thing means ‘related to.’ Remember Mount Saint Helens?” Gram has a good memory for an old person and knows everything. On May 18, 1980, Mount Saint Helens blew up. Three days after my birthday.

“Ashes from breakfast to Sunday!” Gram hollered. “Breakfast to Sunday!”

The ashes were gray sand that got in my mouth when I went outside, just like the stuff Doctor Reddy used when he cleaned my teeth.

“What’s breakfast to Sunday?” I asked.

“Don’t be smart.” Gram always cautioned me about being smart.

At ten, I was still in the A’s. Gram and I sat down and added it up. Our dictionary has 75,000 words and 852 pages. If I did one word a day, it would take me 205 years to finish. At three words, it would take 51 years. If I did five words, it would take 12 years and 6 months to get through the whole book. I wrote this all down. It is true because calculators do not lie and we used a calculator. Gram said we needed to rethink.

“Does that mean we made a mistake?” I asked.

“No, it’s not a mistake to rethink. Rethink means you get to change your mind. You’re never wrong if you just change your mind.” Gram clapped her hands together to get my attention and make sure I was listening. “Pick up the pace, Perry,” she said. “We have to pick up the pace.”

That is when we got our subscription to Reader’s Digest. We bought it from a girl who needed money for her school band to go to Florida.

“This is better than chocolate bars!” Gram was excited when the first one came. “Word Power! Here you go, Perry!”

It was the February issue and had hearts on the cover. We saved every copy that came in the mail. I remember I was on the word auditor. An auditor is a listener. It says so in the dictionary and in Reader’s Digest Word Power. Answer D. A listener. I decided right then to be an auditor. Answer D. I remember this.

We picked up the pace and by the time I turned thirty-one, I was on page 337. Gram was right. That day my words were herd, herder, herdsman, here, hereabouts, and hereafter. Hereafter means future.

“You have to think of your future!” Gram warns about the future each time I deposit my check in the bank. Half in checking and half in savings. For my future.

“It is very important to think of your future, Perry,” she tells me, “because at some point it becomes your past. You remember that!”

My best friend, Keith, agrees with everything Gram says.

“That L. It sure does stand for Lucky, Per.” Keith drinks beer wrapped in a brown paper sack and calls me Per for short. He works with Manuel, Gary, and me at Holsted’s Marine Supply. I have worked for Gary Holsted since I was sixteen years old.

Keith is older and bigger than me. I do not call him fat because that would not be nice. He cannot help being older. I can always tell how old people are by the songs they like. For example, Gary and Keith like the Beatles, so they are both older than me. Gram likes songs you never hear anymore, like “Hungry for Love” by Patsy Cline and “Always” by somebody else who is dead. If the songs you like are all by dead people, then you are really old.

I like every kind of music. Keith does not. He goes crazy when Manuel messes with the radio at work.

“Who put this rap crap on? Too much static! The reception is shit! Keep it on oldies but goodies.” Keith has to change it back with foil and a screwdriver because of the reception. Static is when somebody else plays music you do not like and you change it because of reception.

Before Holsted’s, I learned reading, writing, and math from Gram and boat stuff from Gramp. After he died, I had to get a job for money. I remember everything Gramp showed me about boats and sailing. Our family used to own the boatyard next to Holsted’s.

“It’s a complicated situation.” Whenever Gram says this, her eyes get all hard and dark like two black olives, or like when you try to look through that tiny hole in the door at night. That is not a smart thing to do because it is dark at night and you cannot see very well.

Just before he died, Gramp took out a loan for a hoist for the yard.

A loan is when someone gives you money then takes collateral and advantage. After that, you drop dead of a stroke by the hand of God.

A hoist lifts boats up in the air and costs as much as a boatyard.

That is what the bank said.

2

Gram says I have to be careful. “You’re suggestible, Perry.”

“What’s suggestible?” I ask.

“It means you do whatever people ask you to do.”

“But I’m supposed to.” I always get in trouble if I do not do what Gram says.

“No. There are people you listen to, and others you don’t. You have to be able to tell the difference.” Gram slaps the kitchen table hard with her hand and makes me jump.

“Like who?” I ask.

We make a list.

“For example, a policeman.” Gram draws numbers on the paper. “He’s number one on the list.”

“I always have to do what Ray the cop says.” I already know this. That is the law. Officer Ray Mallory has a crew cut and wears sunglasses even when it rains.

“Don’t ever call Ray a cop. He’s a policeman.” When Gram scolds, her eyebrows get all bushy and her hair comes out of its bun like it is mad too.

“Keith calls him a cop,” I say.

Then I remember when Kenny Brandt called him a cop, Ray chased him all the way down the street and Kenny had to hide behind Mrs. Callahan’s bushes until way after dinnertime. I do not want to be chased by the police and go to jail.

“Okay, a policeman,” I agree.

Gram is number two on our list. I do everything she says. I do not ever do what Chuck at church says because he is a jerk. A jerk is someone you cannot trust, so Chuck is not on our list. Gary Holsted is number three, because he is my boss. I do not do what Manuel says.

“Manuel’s a jackass, Per! A jackass is an animal, and you don’t do what animals say.” Keith helps us with the list.

“Keith, you should be on the list.” I say this at least two or three times a week. I want to make him number four.

“I don’t need to be on any list, Per,” he says. Per sounds like pear, but I am not a fruit. Keith is not on the list because he is my friend. I never have to do what he says. A friend is someone who calls you something for short like Per for Perry. You never have to do what friends say, but you want to, because you are friends.

We add and subtract people from our list all the time. Sister Mary Margaret used to be number five on the list, but Gram took her off because she tried to collect money from us.

“That goddamned church has enough money! It doesn’t need ours!” Gram was mad and used a big pink eraser to rub out Sister Mary Margaret’s name. When Sister is nice to us at bingo, we put her back on the list. She goes on and off so much the paper beneath her name is almost worn through.

On rainy days, I take the bus to work. On nice days, I ride my bike down the hill to Holsted’s. It rains a lot here, so mostly I take the bus. It takes ten minutes and stops right in front of our house in Everett, Washington. Not in the middle of Everett, on the edge.

“Hanging on the goddamned edge of Everett.” Gram squeezes her fingers tight like killing a bug when she says this. Blue veins stick out on her hand.

Everett stinks. When I ask why, everybody says something different.

“It’s because all of us fart at the same time.” Keith laughs, then lifts one cheek and lets one go.

“Don’t be smart! It’s because of the paper mills.” Gram smacks Keith in the head with her paper for farting.

“What stink?” Gary asks. “I don’t smell a thing.” He has allergies and sniffs a squeeze bottle. That is gross.

“I think it depends on your nose,” I tell them. “Some noses are fast and smell all the stinks. Some are slow and they don’t. I have a very fast nose. I smell lots of stink.”

“You sure do, Per! You sure do. You got a great nose.” Keith farts again. I know because I smell it.

I am lucky to live with Gram. I have been with Gram since I was a baby. I am the youngest. There is John, my oldest cousin-brother. He has never lived with Gram. He looks just like me except he is taller, has jagged teeth, a gray-brown mustache, and gets married a lot. David is next oldest and looks just like John except he is shorter, thinner, and has blue eyes. He is married to Elaine. Gram calls her different names like That Woman and HER. David has never lived with Gram either. He is an MBA.

“MBA! It means Must Be Arrogant, Perry. You remember that! Marrying The Ice Queen is his comeuppance.” Gram cackles like a witch on Halloween when she says this and rubs her hands together like she is trying to start a fire. She is good at witch laughs.

Gram says comeuppance means you get what you deserve.

John is a lawyer. David’s wife Elaine is a lawyer. My mother Louise married my father who was a lawyer, but I think he is dead. I am named after a very famous TV lawyer.

“Perry Mason. The only lawyer worth a goddamn!” Gram said.

I only got the Perry part. That’s okay.

“Money runs through your mother’s hands like water. You re-

member that, Perry. Marrying a lawyer is as bad as being one! You remember that too!” Gram warns. “Not one of them goes on our list!”

I call my mother Louise. It is a pretty name and she likes it better than Mother. Sometimes I cannot tell who she is because I do not see her very often and her hair is always different. It gets longer or shorter and changes colors. That is scary. I hope my hair stays just like it is.

I do not live with any of them. I live with Gram.

“Everybody in our family is either a lawyer or married to one,” I tell Gram, “except for you and me.”

“That’s a good thing, Perry,” she says. “It’s a goddamned good thing.”

Gram can blow smoke out the side of her mouth and through her nose. She limits herself. “Only two menthol cigarettes a day. Count ’em. One. Two.”

She will hold them up in front of me.

Sometimes, Gram loses count.

Lottery

- paperback: 336 pages

- Publisher: Berkley Trade

- ISBN-10: 0425222209

- ISBN-13: 9780425222201